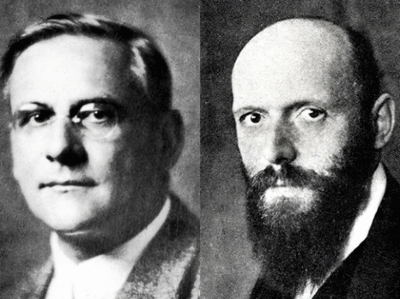

Kurt Gödel (left) and Albert Einstein in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1950.Credit: Imagno/Getty

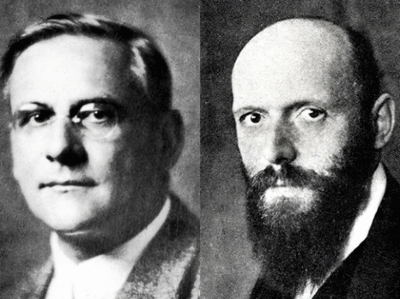

The 2023 film Oppenheimer narrates the story of the atomic bomb entirely from the perspective of its eponymous hero. But there’s much that is left out. It is well-known that US efforts to build the bomb started years before physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer took over as director of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico in 1943. That project was initiated by fellow physicist Leo Szilard. Concerned by the pace at which nuclear-science discoveries were being made in Germany, Szilard persuaded Albert Einstein in August 1939 to write a letter to then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning him of the risk of an atomic bomb in Adolf Hitler’s hands.

But Szilard wasn’t the only physicist to try to use Einstein’s prestige to alert the president. Viennese physicist Hans Thirring independently arrived at the same idea. Thirring’s attempt petered out, but deserves a footnote in history, if only because it involves none less than Kurt Gödel in the unexpected role of a secret agent. The tale has all the trappings of an Alfred Hitchcock movie.

Vienna Circle

Gödel, a mathematician and philosopher, was called by Einstein “the greatest logician since Aristotle” — a phrase coined in 1924 that stuck. Yet when Kurt enrolled at the University of Vienna 100 years ago, he started out in physics. Relativity was all the rage then, and Gödel’s professor, Hans Thirring, was an expert. He had just co-discovered an important feature of the Universe — that the gravitational field of a spinning ball (such as Earth) differs from that when the ball is still, now known as the Lense–Thirring effect. The difference is tiny, however, and it wasn’t measured until 80 years later, using first-rate space technology.

The avant-garde philosophers of the Vienna Circle, a group of self-appointed heralds of the scientific world view, also influenced Gödel and turned his mind towards the foundations of mathematics. By age 25, he had discovered his ‘incompleteness theorem’, which states roughly that there is no consistent formal system in which all arithmetical propositions can be proved. This was an epoch-making result.

Gödel became one of the first postdocs to be invited to the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. But when he returned from the United States to Vienna in 1934, he had a nervous breakdown. Indeed, bouts of persecution mania and fears of poisoning would dog him for the rest of his life. Thus, during the 1930s, Gödel shuttled between seminars in Vienna, the Institute for Advanced Study and mental-health clinics.

Why Oppenheimer has important lessons for scientists today

His mathematical work shifted to ‘set theory’, especially the theory of infinites. And again, he achieved a landmark result. He obsessively pursued the ‘continuum hypothesis’, which states roughly that the infinitude of real numbers is next largest to that of natural numbers. Gödel managed to show that this hypothesis is compatible with the axioms of set theory — a brilliant feat. His shorthand notebooks from that period, which are currently being deciphered and published, show that he pursued in parallel a stupendous range of interests, including parapsychology and quantum mechanics — two fields that also engrossed his former physics professor, with whom he had never lost touch.

Thirring was charismatic, popular with his students and brim-full of ideas. He had invented a cape-like ‘hover-coat’ for skiers and held a patent on films with sound. He, too, was in close touch with the hard-nosed ‘positivists’ of the Vienna Circle, who thought that knowledge comes only from experience and logical analysis. But this did not dampen Thirring’s interest in paranormal phenomena.

To hold a truly scientific world view, one must be ready to swim against the mainstream. This applies to political tides, too: Thirring was one of the woefully few in Vienna to stand up firmly against the flood of Nazi students after Hitler came to power. The ‘brownshirt’ storm troopers — the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party — could not accuse him of being of Jewish descent, but his support of Einstein (who was Jewish) was bad enough in their eyes. And in 1938, as soon as Austria was annexed to the Third Reich, 50-year-old Thirring lost his professorial chair. But he did not lose contact with former colleagues. And he was well aware that, in physics labs everywhere, everyone was talking about nuclear fission — the division of the atomic nucleus and the resulting release of energy — which had just been discovered in Hitler’s Berlin.

Mounting concern

In the summer of 1939, after reading an article in the scientific journal Die Naturwissenschaften by Siegfried Flügge — later a leading member of Uranverein, the ominous ‘Uranium Club’ that was behind the German effort to build a nuclear bomb — Thirring had learnt enough to feel that the US government should be warned. Like Szilard, and at about the same time, he came up with the idea to use Einstein to alert Roosevelt. But how could Thirring contact Einstein? The Gestapo, the Nazi secret police force, would intercept every phone call or letter from Vienna to Princeton, where Einstein lived.

This is when Thirring heard that Gödel happened to be on a brief visit to Vienna, to see his mother and take his wife Adele back with him to Princeton. Why not use Gödel as a secret messenger to reach Einstein? Thirring entrusted Gödel confidentially with the task of warning Einstein about Hitler’s bomb.

Unfortunately, the plan proved ill-fated. Gödel’s departure was delayed for nearly four months by an avalanche of bureaucratic hurdles. At times, escape looked hopeless.

Difficulties and chicanery piled up. After Germany annexed Austria, Gödel automatically became a German citizen, and had to return his old passport. The visa for multiple re-entry into the United States was in the old passport, and the hopelessly overtaxed US consulate could not simply transfer it to the new one. Gödel had to re-apply to enter the United States, and thus join a queue of thousands who were desperately trying to escape from the Reich.

The ‘hover-coat’ designed by Hans Thirring.Credit: BNA Photographic/Alamy

Gödel had also lost his lectureship, and thus his professorial status. The Nazis were re-structuring academic life, and Gödel’s former contacts aroused their suspicion. Would he be able to represent ‘New Germany’ abroad? A minor bureaucrat had found fault with Gödel’s previous journey to the United States; the revenue service questioned the few hundred dollars on his account. It seemed he was of Aryan descent, but where was his grandparents’ marriage certificate, and that of his wife’s grandparents? Administration ran amok.

As one Viennese eye-witness, the writer Leo Perutz, described it: “Obscure offices that no one had ever heard of before would suddenly emerge from hiding, would make their demands imperiously known, and would insist on being satisfied, or at least noticed and consulted.”

Gödel and his wife had moved out of their flat in September — but because they couldn’t leave the country as planned, they had to look urgently for new lodgings. On top of it all, a mustering commission of the German armed forces, the Wehrmacht, declared Gödel fit for garrison duty. It was like a bad dream. Indeed, many years later, he would still be plagued by nightmares about being trapped in Vienna.

Perilous flight

In the end, thanks to vigorous interventions by mathematician John von Neumann and others at the Institute for Advanced Study, the visas came through in early January 1940. By then, Hitler’s troops had overrun Poland, and Europe was torn apart by war. The United States wasn’t involved yet, and some neutral vessels still plied the Atlantic Ocean. However, they were routinely searched by Allied warships, and all German passengers were sent to internment camps. On top of that, there was the risk of running through the periscope sight of a trigger-happy German U-boat skipper. Obviously, an Atlantic crossing would not do.

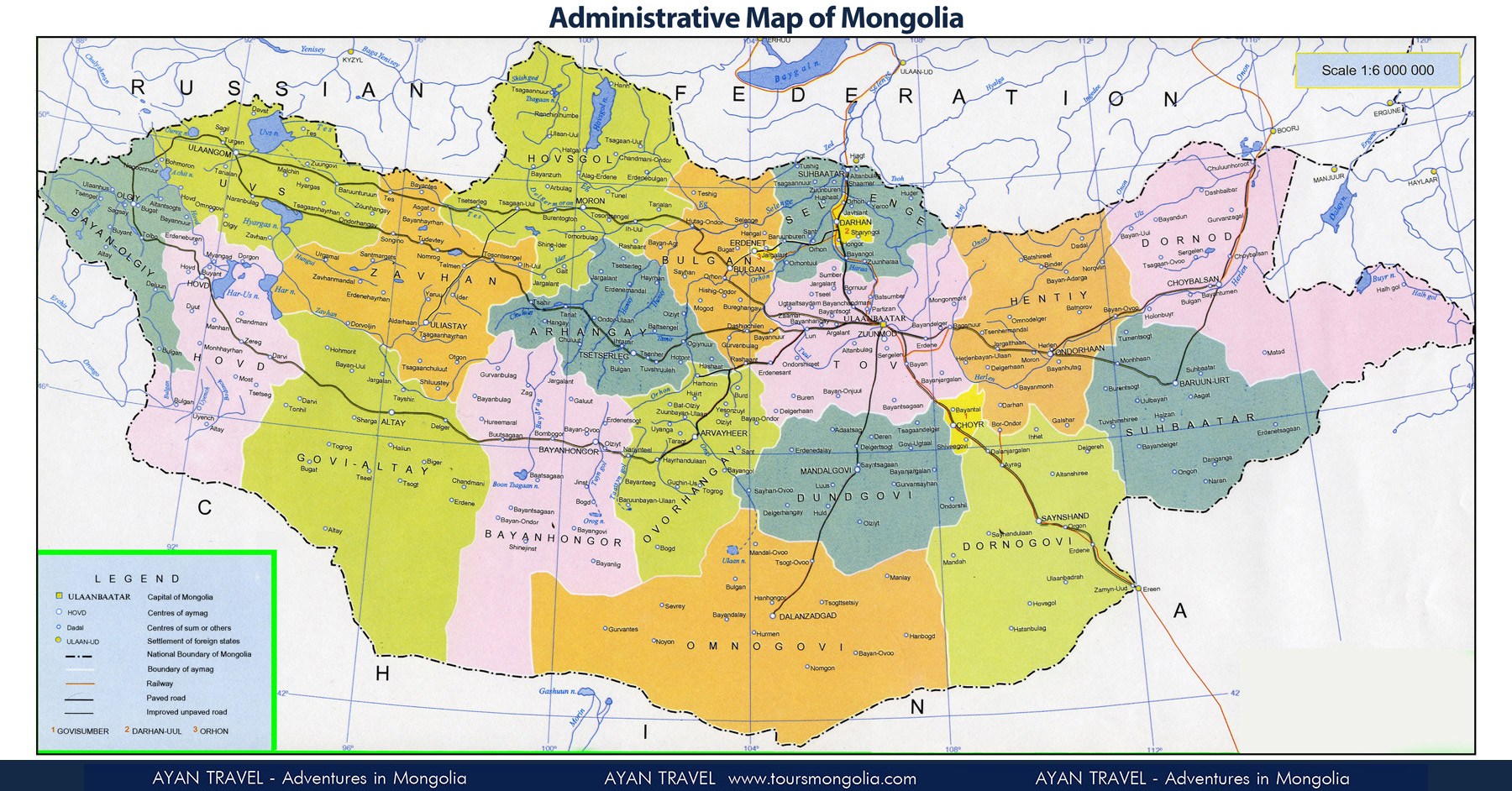

The only way out was the other way around: eastward, through Siberia and the Pacific. A tight-rope act, but just feasible. The Soviet Union and Japan were both waging wars, but not against Germany, or the United States, or each other.

Thirring’s plan was still alive, and on the eve of Gödel’s departure, the dauntless physicist met him and relayed the secret message. It was by no means sure that it would reach its destination. At each hitch, the Gödels risked being stopped. They had a long way to go.

To Berlin first, for some final stamps on their documents. From there, across half of Prussia, to reach occupied Poland, with its bombed railway stations and baleful troop transports clustering the sidings. On through twilight Latvia and Lithuania, and into Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union. Each border crossing took hours. Each luggage search was nerve-racking, and each knock on the compartment door was ill-boding. Finally in Moscow, the Gödels spent a night in the gigantic Hotel Metropol, a gloomy block housing mostly Communist Party delegates, some anxiously awaiting their upcoming trials for disloyalty. These were the heydays of communist purges and spy scares.

How Viennese scientists fought the dogma, propaganda and prejudice of the 1930s

At Yaroslavski station in central Moscow, the Gödels boarded the Trans-Siberian Express. Its other terminus was more than 9,000 kilometres away, in Vladivostok. During the seemingly endless nights of ice and snow, the train accumulated a colossal delay. After finally reaching Vladivostok, they had to take a ship — often running behind schedule — to Yokohama, Japan. While in Berlin, Gödel and Adele had booked a cabin in the SS President Taft for the leg from Yokohama to San Francisco, California. Inevitably, they missed the ocean liner, and had to wait for two weeks for the next one, the SS President Cleveland.

Once aboard, things started picking up. A day’s stopover in sight of Oahu, Hawaii, came as a welcome change from icy Siberian train platforms. The coast of California rising from the horizon was the climax. Years later, Gödel would still enthuse: “San Francisco is absolutely the most beautiful city I have ever seen.” There was just one last formality before landing: the immigration papers, with their obnoxious queries — “Have you ever been a patient in an institution for the care and treatment of the insane?” No.

Another railway ticket; another trans-continental ride, now in an elegant Pullman sleeper train; and the safe haven of Princeton at last, after almost two months of travelling. Gödel’s long-time friend, economist Oskar Morgenstern, reported in his diary on 12 March 1940: “Gödel arrived. This time with wife. Via Siberia. When asked about Vienna: The coffee is wretched!”

After having circled three-quarters of the globe, Gödel had reached Einstein’s doorstep. He could finally fulfil his mission. Despite all obstacles, Thirring’s message had arrived. Quite conceivably, it could save the world.

And this is where Gödel failed.

He confessed it to Thirring more than three decades later: on meeting Einstein, Gödel had not transmitted the warning, but merely “greetings from Thirring”. The bizarre excuse: he, Gödel, had felt that a nuclear chain reaction would be possible only “in a distant future”.

Lost legacy

What did Thirring make of this? We can only wonder. He had outlasted the Third Reich unbowed, reassumed his professorship and become one of the firmest voices against nuclear armament. By then, however, Einstein’s letter to Roosevelt, prompted by Szilard, was public knowledge. Thirring’s son Walter, who was also a theoretical physicist and a colleague of mine in Vienna, later told me that his father was always uneasy about his (imagined) role in the bomb project. Hans, who was an inveterate pacifist, saw himself as a link in the causal chain that had led to the horrors of the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945. Only in 1972, shortly before his death and already weakened by a stroke, did he learn that his message had never reached its goal.

As a secret agent, Gödel had proved a dud. But then again, fortunately, the spectre of Hitler’s atomic bomb had turned out to be no great shakes either.