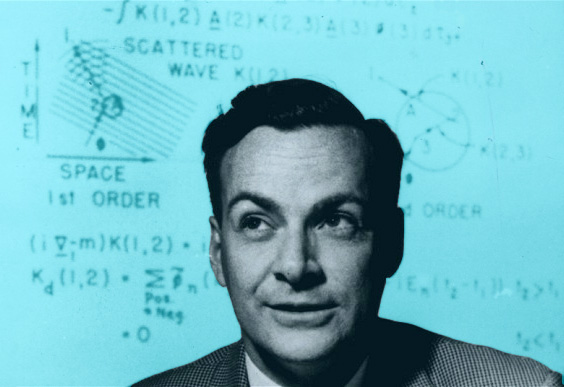

Among the most beautiful is the third lecture in the series, titled “The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences,” in which Feynman, eloquent and enthralling as ever, illustrates the connectedness of everything to everything else — or what poet Diane Ackerman memorably called “the plain everythingness of everything, in cahoots with the everythingness of everything else.”

Transcript below.

A poet once said, “The whole universe is in a glass of wine.” We will probably never know in what sense he said that, for poets do not write to be understood. But it is true that if we look in glass of wine closely enough we see the entire universe. There are the things of physics: the twisting liquid which evaporates depending on the wind and weather, the reflections in the glass, and our imagination adds the atoms. The glass is a distillation of the earth’s rocks, and in its composition we see the secrets of the universe’s age, and the evolution of the stars. What strange array of chemicals are in the wine? How did they come to be? There are the ferments, the enzymes, the substrates, and the products. There in wine is found the great generalization: all life is fermentation. Nobody can discover the chemistry of wine without discovering the cause of much disease. How vivid is the claret, pressing its existence into the consciousness that watches it! If our small minds, for some convenience, divide this glass of wine, this universe, into parts — physics, biology, geology, astronomy, psychology, and so on — remember that nature does not know it! So let us put it all back together, not forgetting ultimately what it is for. Let us give one more final pleasure: drink it and forget it all!

The Feynman Lectures on Physics offers an abundance of more such illuminating insight and immutable truth on the interplay between science and everyday life. Complement it with Feynman on good, evil, and the Zen of science, his case for the universal responsibility of scientists, and his little-known drawings.

Well in all fairness, these days we're already supposed to accept a lot of things that we flat-out know just aren't true, so what's one more thing. Warming means cold. Cool.

"Dear Sir, I am very much gratified on perusing your letter of the 8th February 1913. I was expecting a reply from you similar to the one which a Mathematics Professor at London wrote asking me to study carefully Bromwich's Infinite Series and not fall into the pitfalls of divergent series. … I told him that the sum of an infinite number of terms of the series: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + · · · = −1/12 under my theory. If I tell you this you will at once point out to me the lunatic asylum as my goal. I dilate on this simply to convince you that you will not be able to follow my methods of proof if I indicate the lines on which I proceed in a single letter. …"This is a hint of what he meant: