“All men having power ought to be mistrusted.” –U.S. Founding Father James Madison

“There are men in all ages who mean to govern well, but they mean to govern. They promise to be good masters, but they mean to be masters.” –Daniel Webster

“Political tags — such as royalist, communist, democrat, populist, fascist, liberal, conservative, and so forth — are never basic criteria. The human race divides politically into those who want people to be controlled and those who have no such desire.” –Robert A. Heinlein

“… the most improper job of any man, even saints (who at any rate were at least unwilling to take it on), is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit to it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.” –The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

[St.] Augustine wrote about ‘libido dominandi.’ …This is the lust to dominate. This is the thing in human nature that draws people to the government.” –Judge Andrew P. Napolitano

“Those who have been intoxicated with power… can never willingly abandon it.” –Edmund Burke

“This must be said: There are too many ‘great’ men in the world–legislators, organizers, do-gooders, leaders of the people, fathers of nations, and so on, and so on. Too many persons place themselves above mankind; they make a career of organizing it, patronizing it, and ruling it” –Frederic Bastiat in “The Law”

“In order to become the master, the politician poses as a servant.” –French President Charles De Gaulle

“The urge to save humanity is almost always a false front for the urge to rule.” –H. L. Mencken

“I believe there are more instances of the abridgement of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations.” –James Madison

“All governments suffer a recurring problem: Power attracts pathological personalities. It is not that power corrupts but that it is magnetic to the corruptible.” –Frank Herbert, Dune

“And those who govern ought not to be lovers of the task. For, if they are, there will be rival lovers, and they will fight. –Socrates

“ Experience hath shewn, that even under the best forms of government those entrusted with power have, in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny. –Thomas Jefferson

“When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in a society, over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorizes it and a moral code that glorifies it.” –Frederic Bastiat

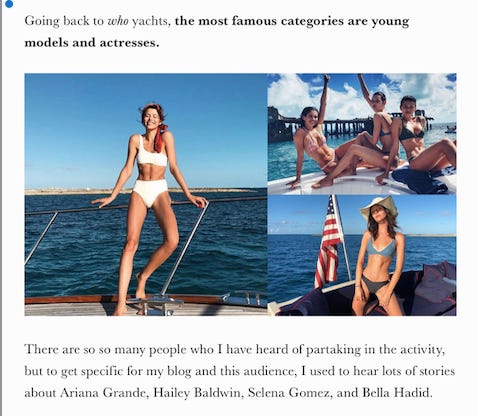

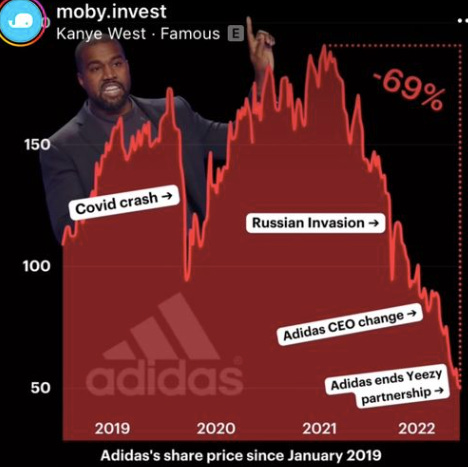

Harvey Weinstein is on trial in LA this week, and apparently his lawyers are worth the money. His appetites were legendary and his requirements were well known. Most paid the price. Which is why the plaintiffs are coming off as colluding. They traded sex for fame. A few bloggers have been chipping away at Dark Hollywood, releasing data, offering theories; some are well educated and have real reporting skills. They are dogged and careful. They drip out the horrifying stories, hidden in fashion sites, or in brief TikToks, their evidence gathered from drivers, staff, servers and cleaners. Reality is far darker than even Epstein and Maxwell’s blackmail and sexual trafficking. New media is the change agent. Maxwell and Epstein’s clients are still at large, still hungry. And many of them picking up the torch are in Hollywood, with a million victims begging, hungry for fame. They and their appetites who are the reason for the breakdown in film and television. Why every film or series is dark to the point of Satanic, why every drama is about violent death, and every year, the viewer has his adrenalin spiked and spiked again. Film and premium television have become fear porn, and many of us – hundreds of millions - watch it every night before we go to bed. What is that doing to us, to our bodies, our emotions, our culture? It's not good. I took a break from television and film for more than a year, then signed onto Netflix to watch the end of Ozark, which is a brilliant piece of work, plausible, linked to the real world, real acting, real writing. But for days afterwards, I was depressed way beyond any normal passing sadness, until I realized that my emotions, my lizard self, had been triggered into terror by the brutal killings, the horror of the lives I was watching. And Ozark is the most coherent of the terrible things on Netflix, Prime and HBO. Start anything, and within minutes, you are watching an appalling act of violence, cruelty as common human discourse, sex as exploitation and nothing else. For kids, a lot of pop music now is violent, when not promoting a disgusting sexuality. Even polite BBC dramas are focused around brutal, violent death. Who is greenlighting this stuff? Who decided that this was what we wanted to see? Who figured out that adrenalin and terror would sell, and upping the terror was the key to success? How much do you know about yachting? Or the private rape rooms at Disney parties? Or how music stars like Dua Lipo are groomed for years, then sprung into stardom? Let’s take each in order. Yachting is how very young movie stars make real money. Almost every single one of them has done it. It’s the only way they can pay for their lives in Hollywood. Most of these girls were so beautiful they were sexualized early. The moment they have a bit of fame, they turn to yachting where they can make a few million every summer. Meghan Markle, Selena Gomez, Hailey Bieber, Bella Hadid, all participated, were invited to lavish yachts where they sleep with billionaires, industry executives, and are paid six figures per night. Howie Mandel’s wife is said to have supplied them out of the cast of Deal or No Deal. Ariana Grande cancelled a concert because a yachting gig would pay her more. Moving onto the companies that hire thousands of children like Disney and Nickelodean, the rumors are in the thousands, the tens of thousands. Why do young women like Miley Cyrus hyper-sexualize themselves? What happened to Lindsay Lohan’s extraordinary talent? Why is Britney child-like and regressed? Why do Selena, Justin Bieber, Demi Lovato all have severe emotional problems? Apparently if Disney stars went to a beach picnic, what they bonded about is how they were raped and by whom. Why do you think Miley Cyrus hates Disney, and would never return, that her persona “Hannah is dead” to her? Why is she alienated from her parents, like so many of the above? Because their parents let it happen. All those kids are broken, were broken, when they were in their early teens. At Disney’s annual parties, at the mansion, the top floor was heavily guarded because those rooms were called rape rooms. The sex was more or less consensual, the girls and boys believed it was a condition of employment. They were called rape rooms, since most sent up those stairs, were underage. At the door, the Disney actresses were told to pick their preference: “Are you open to women? Men? Both?” That, it was explained, was their only choice. According to servers at these parties, the attendees are executives at huge corporations, filthy rich, incredibly successful, managing billion dollar companies. They are so rich and powerful that “they do the most inhumane things to feel some sort of rush, the goal is the adrenaline. It’s the power over a child, that makes them feel unstoppable”. The rape rooms at Disney parties are well known. Buying a young star’s virginity for huge money is better than a limited edition Ferrari. Anyone can buy that. This is the kind of blind that is typically released by victims. These are the girls our daughters and granddaughters idolize. The final abomination is grooming. A young talent comes to Hollywood, she is seen as a likely contender, a wealthy impresario picks her up and sends her around to have sex with his friends, and anyone who would be likely to help her out. They work with her on her looks, voice, styling, and eventually, after years of forced prostitution, she is given a chance with all the bells and whistles. Fall out of line, like Kanye West, and this is the kind of message you get, allegedly sent to Kanye by his former personal trainer. The burden that lies on the populists next Tuesday is larger than they know. The grooming of children in schools is merely the beginning. What I describe above waits seething under the surface. It will blight their childrens’ lives. It is full-on Satanic. If the producers of our popular culture are as corrupt and evil as I describe, their power must be limited. I apologize for the rawness of this, but no one is writing about it in the mainstream. It is hard to look at, but it must become common knowledge. It is the only way it can be stopped. You’re a free subscriber to Welcome to Absurdistan . For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. © 2022 Elizabeth Nickson |

100th Infantry Battalion Veterans

Education CenterEarl Finch

The One Man U.S.O.

Earl Finch [442nd Regimental Combat Team Archives]

Earl Finch met his first Japanese American G.I. in the summer of 1943. He had closed his Hattiesburg, Mississippi store at the end of the day and was walking to his car, when he noticed several small men wearing ill-fitting American uniforms. He approached one of the men, Richard Chinen, who was peering through a store window. “Welcome, soldier,” said Finch, whose greeting soon included an invitation for dinner.

Finch was the proprietor of the Earl Finch Company, which offered “Work Clothes, Army and Navy Goods, Sporting Goods” to thousands of American soldiers who trained at nearby Camp Shelby. While only 27 years old, he was an experienced and accomplished businessman, having had to leave school at age 10 to help support his family. In addition to the store, Finch owned a bowling alley and second-hand furniture store, but he wasn’t a wealthy man. Content to live with his aging parents in the southern Mississippi town of 25,000, he was shy, with few friends. Finch, a bachelor, didn’t drink or smoke and had never traveled farther than 100 miles from home.

Finch had tried to volunteer for the U.S. Army but was rejected because of a heart ailment. When his younger brother, Roy, was inducted and shipped out, Finch decided that his patriotic duty was to offer hospitality to soldiers. Reasoning that foreign troops were in the most need of friendship, Finch entertained Chinese airmen and French and British seamen in New Orleans on several occasions.

Finch’s mother, Aloise, was partially paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair. Nonetheless, when her son arrived home with his guests, she prepared a hearty Southern meal. In their conversation that evening, Chinen explained to Finch that they were from Hawaii and had volunteered for the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team to prove their loyalty to the United States. (Chinen would later be reassigned to the 100th Infantry Battalion to help replenish its depleted ranks.)

In the past, Finch had invited soldiers to his home, but never saw them again. Therefore, he was pleasantly surprised to return the next afternoon and discover the Hawaii boys on his porch talking and laughing with his mother. In addition, the men had purchased roses for her in appreciation for the previous night’s hospitality. The small token of gratitude impressed Finch immensely. Finch soon recognized that more than any other group of soldiers he had encountered, these Nisei (“second generation” in Japanese), children of Japanese immigrants, appreciated the democratic values they were fighting for. Finch committed himself to helping the young Nisei gain acceptance in his hometown.

Mr. Aloha

The Finch home was too small to accommodate more than a few soldiers, so he purchased a 350-acre ranch outside of Hattiesburg. At first, Finch limited his generosity to the Hawaii soldiers, reasoning that they were the farthest from home. He soon learned, however, that mainland Nisei carried an additional burden: They had volunteered directly from U.S. internment camps, leaving their parents and siblings still unjustly confined behind barbed wire. Most of them had little or no money. Over the next few months, Finch entertained several thousand soldiers—from both Hawaii and the mainland, staging several large events at his ranch such as barbecues, watermelon picnics and even a rodeo to which he invited 600 soldiers.

To make them feel at home, Finch imported Japanese food products like shoyu, bamboo shoots, tofu and Asian vegetables from Chinese restaurants in Chicago and New York. He imported mangoes from Bermuda and pineapples from Cuba. He even butchered a cow so that the soldiers could enjoy a meal of sukiyaki.

In addition, although Finch did not have a personal interest in sports, he became deeply involved with various athletic programs because the 422nd included some of the best athletes in the country. Finch was the team sponsor of the 442nd team that won the Camp Shelby baseball championship. When Finch heard the Southern Amateur Athletic Union Swimming Championships were being held in New Orleans, he arranged for ten Nisei swimmers to compete in the event. He rented a truck and made arrangements for the team to practice at the swimming pool of nearby University of Southern Mississippi. He paid for the train fare as well as their stay at the posh Roosevelt Hotel. Although they were out of shape, the Nisei swimmers dominated the best Southern swimmers to win the team title.

Finch was also among the individuals who helped secure the location for a separate club which would serve the Nisei soldiers. The “Aloha” USO in Hattiesburg was opened and operated by the wives of several soldiers who had relocated there. Finch was at the club practically every day and received some 200 letters per week there from Nisei soldiers, their families and friends. The correspondence often included small donations to help finance his charitable activities.

Soldiers’ Sacrifice

By September 1944, the soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion had entered combat, suffering heavy casualties in the Italian campaign. The following June, the 442nd RCT joined the 100th in combat. Finch, who had become the executor for some 1,500 wills, sadly received death notifications of his friends. He visited many of the grieving, Issei (first generation) parents in internment camps. (At war’s end, Finch would also assist former internees returning to the West Coast, helping them find jobs or giving them loans to relocate and start businesses of their own.) To those he could not meet, he sent messages and flowers. Because of the high casualty rates for both the 100th and the 442nd, in one year, Finch traveled some 75,000 miles across the nation, visiting soldiers recovering from their wounds and their parents.

Among the many whom Finch called upon was 26-year-old First Lieutenant Spark M. Matsunaga of the 100th, who was recuperating from his injuries at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. “As soon as he heard that I and several other wounded officers were there, he came up from Mississippi to visit us,” Matsunaga recounted years later when he was a U.S. Senator.

Earl Finch with Shelby Serenaders [442nd Regimental Combat Team Archives]

As the casualties of the 100th increased, replacements had been sent from the 1st Battalion of the 442nd. By the time the regiment left for Europe, the remaining men in the 1st Battalion stayed to help train the new waves of Nisei recruits. To lift morale, Finch organized the Shelby Serenaders, a Hawaiian music group. According to Claude Takekawa of the 442nd, Finch simply came into their barracks one day and asked for volunteers. “We picked up some friends and he came back about a week later and we auditioned for him,” said Takekawa. “He said, ‘Okay that’s pretty good.’ He went to the battalion commander and he got us a ten-day furlough. We went to New York and he put us up at the Waldorf Astoria, the best hotel over there. Can you imagine?”

With ukuleles, bass, and hula dancer (Ken Okamoto of the 442nd performed in a grass skirt), the Shelby Serenaders entertained the wounded at the Halloran General Hospital in New York. On August 12, 1944, they held a second performance at the Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C. Many patients were members of the 100th/442nd. Finch decided to sponsor a tour of the band, which ultimately traveled some 35,000 miles and performed for approximately 25,000 wounded soldiers in hospitals around the country.

In January 1945, Finch reserved the ballroom at the Hotel Astor in New York and threw a huge bash with Hawaiian music and hula for 150 returning soldiers. The event prompted The New York World-Telegram to dub Finch a “One Man USO.” In June, Finch threw another party in Chicago, inviting Nisei veterans from hospitals in Chicago, Michigan and Utah. A month earlier, Germany had surrendered, ending the war in Europe.

Earl Finch with a key to the city of Honolulu [442nd Regimental Combat Team Archives]

On March 5, 1946, Finch visited Honolulu and was greeted with the largest and warmest reception ever given to a private citizen in the history of Hawaii. For 25 days, island families toasted their friend from Hattiesburg. In the three months following his Hawaii visit, Finch visited an additional 3,000 hospitalized Nisei soldiers in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago. Despite his busy schedule, Finch was in the nation’s capitol on July 15, 1946, when the 100th/442nd received the Presidential Unit Citation from President Harry S. Truman.

“When the ‘Go For Broke’ outfit marched to the White House . . . Mr. Finch was there,” recounted 442nd veteran Larry Sakamoto. “He had tears in his eyes. You could tell he was the proudest person on the earth.”

In August 1965, Finch died of a heart attack. His big, generous heart, which had given so much to so many, failed him after only 49 years. The 442nd Veterans Club handled all the funeral arrangements, and more than 300 friends attended a Central Union Church service conducted by former 100th chaplain Israel Yost and 442nd chaplains Masao Yamada and Hiro Higuchi.

Finch was buried at Diamond Head Memorial Park on August 25, 1965. His headstone, a simple bronze plaque, only lists his name and the dates of his birth and death. Missing are his countless acts of kindness and the thousands of lives that he touched. But Earl Finch, who just wanted to be a good friend, would have had it no other way.

Today's selection -- from Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees by Jared Farmer. There are bristlecone pine trees estimated to be over 4,000 years old, making them older than California’s giant sequoias:

"In January 1956, the NSF awards [Edmund] Schulman a three-year grant to further his investigation into longevity under adversity. At last, he has funding to hire his own full-time assistant. He sees the summit in his mind: a definitive tree-ring survey of his model species in its model location. He types a letter to National Geographic, pitching an article on 'Methuselah pines.' My study is comparable in scientific importance to Douglass's 1929 article on the dating of Puebloan ruins, he states matter-of-factly. An editor responds: The magazine might be interested, but only if your work could be presented in a way that appeals to 2.1 million laymen. If not, the magazine could make room for a 'filler' piece called 'The World's Oldest Trees' that covers sequoia, too. Readers like big old trees.

"In June, Edmund embarks upon his life's most important fieldwork. He's tempting fate at high altitude: his doctor has ordered him to stay home. Alsie, who suffers from atrial fibrillation, chooses not to come along. I'll be out of touch for weeks, he writes his brother, after scolding him for keeping him in the dark about the latest family crisis. In an emergency, he says, you can probably reach me through the Navy station. 'Big things are afoot.'

|

"Schulman doesn't get carried away like Humboldt. He knows the Patriarch and its largish neighbors aren't that old -- relatively speaking -- just lucky. Their habitat, though harsh, is slightly better than that of others in the Whites. To find the oldest bristlecones, Schulman seeks out steeper, looser, drier slopes. He finds strange pines whose trunks grow as slabs instead of rounds. Sustained by a single strip of bark, such a tree grows horizontally more than vertically, and ever so slowly. Its growth rings are infinitesimal. It rakes all his strength to crank his borer through the perdurable wood.

"In his first NSF summer, to his amazement and delight, Schulman 'hits the pith' of three pines older than 4,000 years, all of them convenient to the military road. He names them, in order of age, Alpha, Beta, Gamma. To build an error-free cross-dated composite chronology for the locale -- for in the idealized world of tree-ring science, there are absolute dates or no dates -- Schulman decides he needs a complete slab. He chooses to sacrifice Alpha. He returns to LA, buys a two-man crosscut saw, and brings along his teenage nephew and Frits Went to be the muscle. They drive in the dark to avoid overheating the Studebaker. The nephew sits in back while Ed and Frits talk science all night. In the glaring light of day, Ed shoots Kodaks of the cutting. Alpha's demise fails to make an impression on the sixteen-year-old, whose uncle conceals the weight of their deed.

"In late September, once Schulman has counted and recounted every ring on the polished slab, the press office at the university announces, 'UA Finds Oldest Living Thing.' They say nothing about the thing being dead. Dr. Schulman has also, they crow, debunked the antiquity of El Arbol del Tule in Oaxaca. Newspapers across the United States pick up the press release, which includes a blurb on the utility of tree rings for meteorological 'backcasting.' It helps that 1956 is a bad drought year. The Office of the President, delighted with the publicity, congratulates Schulman personally.

"Not everyone is happy that dwarf pines have pulled rank on giant sequoias. The San Francisco Chronicle runs a snarky, casually racist opinion. Ancient bristlecones look 'terrible-half-dead, with little if any foliage, warped and writhing roots, and twisted, stubby branches.' Schulman's bristlecone stand compares to a redwood forest 'as an Indian shell mound does to the Cathedral of Cologne.' At least it's still in California.

"The formal announcement of the discovery -- again without acknowledgment of arboricide -- appears simultaneously in Schulman's Dendroclimatic Changes in Semiarid America. This magnum opus, long in the making, contains analyses of one-third of a million rings. The bristlecone data is so new that it appears as 'Appendix C: Millennia-Old Pine Trees Sampled in 1954 and 1955.' In the acknowledgments to this technical volume, full of standard deviation calculations, correlation coefficients, and hand-drawn graphs, Edmund says his 'indebtedness to Alsie' is 'indeed great.' He thanks her for seventeen years of discussing 'so many research problems.'

"Publicity requests come thick and fast that fall. National Geographic is suddenly very interested. They'll send a photographer as soon as he drafts a story. In the meantime, Schulman makes the two-day drive back to the Whites to meet a cameraman from Life, the other leading pictorial magazine. He poses for a series of black-and-white shots. In one, he stands heroically, wearing a straw fedora, while screwing an extra-long increment borer into a hulk of a pine. In another, hat off, Schulman crouches at the remains of Pine Alpha, touching the stump with both hands, with the High Sierra in the background. Uncharacteristically, he looks happy. Life doesn't include either portrait in its brief article, 'The Oldest Thing Alive,' which reassures readers that cores can be taken without harming the tree. Only a 'pinprick,' Schulman tells Tucson's evening paper."

|

||||

| author: Jared Farmer | ||||

| title: Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees | ||||

| publisher: Basic Books | ||||

| date: Copyright 2022 by Jared Farmer | ||||

| page(s): 242-244 | ||||

|

On October 17th, technicians completed the replacement of the cables with carbon steel versions. Following proper procedure, they replaced each cable one at a time, ensuring that the existing configuration was maintained — only, that configuration was wrong, and nobody noticed.

Unaware that their aircraft was dangerously unairworthy, the pilots taxied to the runway and took off normally at 13:31, climbing away into the dense rainclouds which blanketed the airport. They had no idea that they were about to be thrust into one of the most dramatic and lengthy in-flight emergencies in recent memory.