How Killer Rice Crippled Tokyo and the Japanese Navy

One stubborn doctor pioneered a cure.

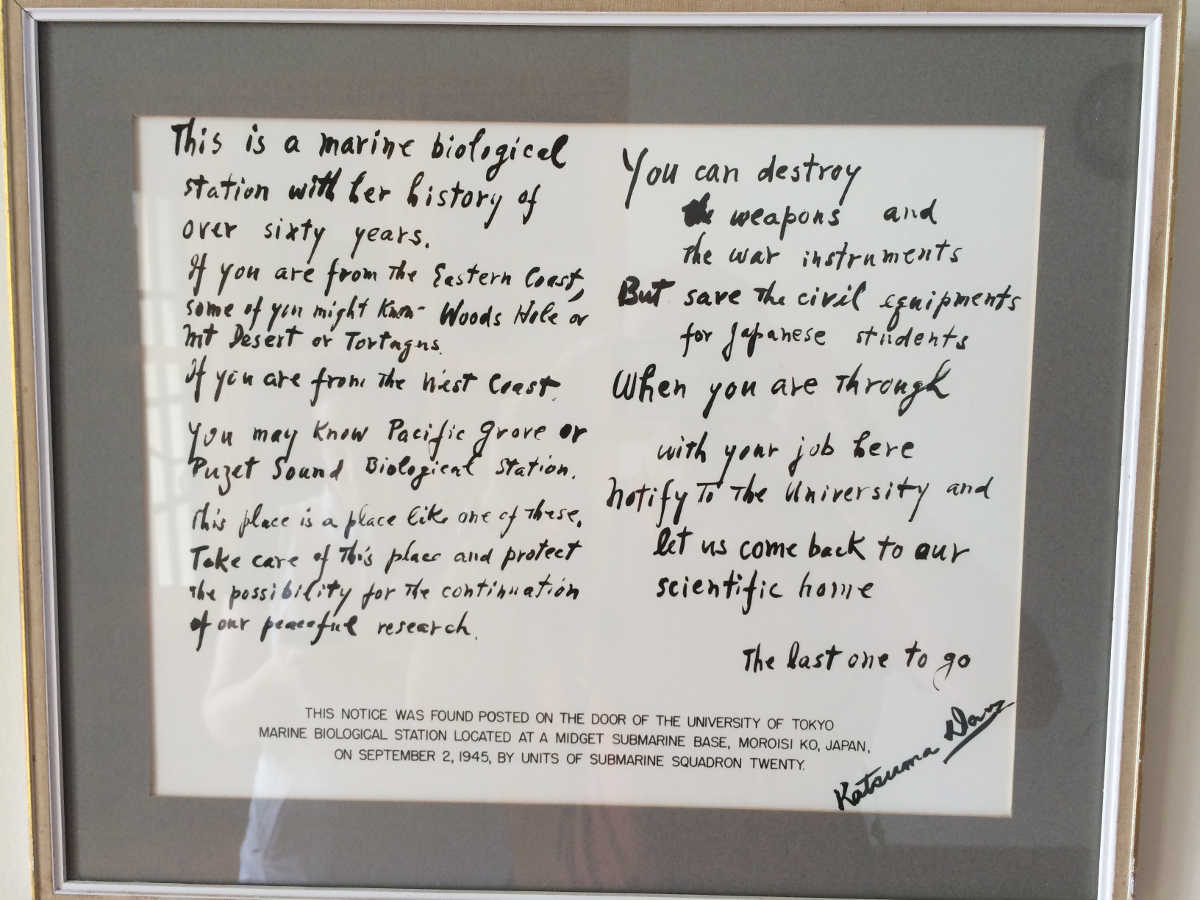

A mysterious illness killed princesses and sailors alike. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0

A mysterious illness killed princesses and sailors alike. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0IN 1877, JAPAN’S MEIJI EMPEROR watched his aunt, the princess Kazu, die of a common malady: kakke. If her condition was typical, her legs would have swollen, and her speech slowed. Numbness and paralysis might have come next, along with twitching and vomiting. Death often resulted from heart failure.

The emperor had suffered from this same ailment, on-and-off, his whole life. In response, he poured money into research on the illness. It was a matter of survival: for the emperor, his family, and Japan’s ruling class. While most diseases ravage the poor and vulnerable, kakke afflicted the wealthy and powerful, especially city dwellers. This curious fact gave kakke its other name: Edo wazurai, the affliction of Edo (Edo being the old name for Tokyo). But for centuries, the culprit of kakke went unnoticed: fine, polished, white rice.

The Meiji emperor and his family. TRIALSANDERRORS/CC BY 2.0

The Meiji emperor and his family. TRIALSANDERRORS/CC BY 2.0Gleaming white rice was a status symbol—it was expensive and laborious to husk, hull, polish, and wash. In Japan, the poor ate brown rice, or other carbohydrates such as sweet potatoes or barley. The rich ate polished white rice, often to the exclusion of other foods.

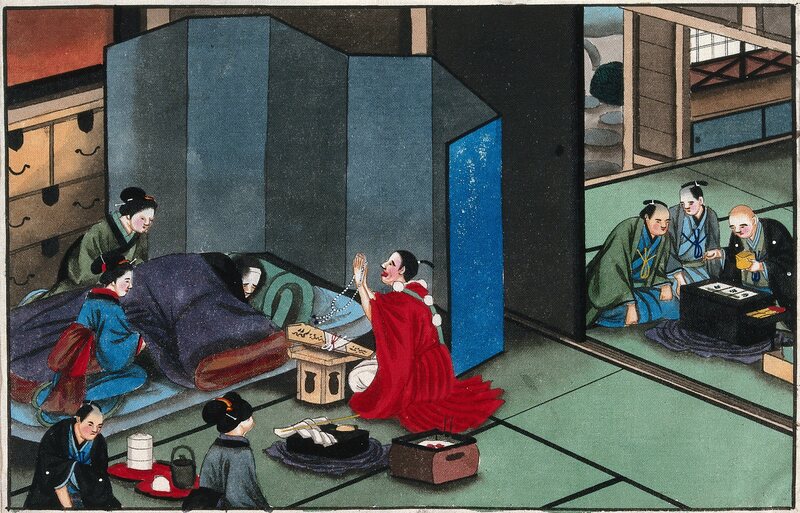

Moxibustion, an ancient technique of burning mugwort atop skin. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0

Moxibustion, an ancient technique of burning mugwort atop skin. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0By 1877, Japan’s beriberi problem was getting really serious. When the princess Kazu died of kakke at 31, it was only a decade after her former husband, Japan’s shogun, had died, almost certainly from the mysterious disease. Machine-milling made polished rice available to the masses, and as the government invested in an army and navy, it fed soldiers with white rice. (White rice, as it happened, was less bulky and lasted longer than brown rice, which could go rancid in warm weather.) Inevitably, soldiers and sailors got beriberi.

No longer was this just a problem for the upper class, or even Japan. In his article British India and the “Beriberi Problem,” 1798–1942, David Arnold writes that by the time the emperor was funding research, beriberi was ravaging South and East Asia, especially “soldiers, sailors, plantation labourers, prisoners, and asylum inmates.”

Into this mess stepped a precocious doctor: Takaki Kanehiro. Almost immediately after joining the navy in 1872, he noticed the high numbers of sailors suffering from beriberi. But it wasn’t until he returned from medical school in London and took up the role of director of the Tokyo Naval Hospital that he could do anything about it. After surveying suffering sailors, he found that “the rate [of disease] was highest among prisoners, lower among sailors and petty officers, and lowest among officers.”

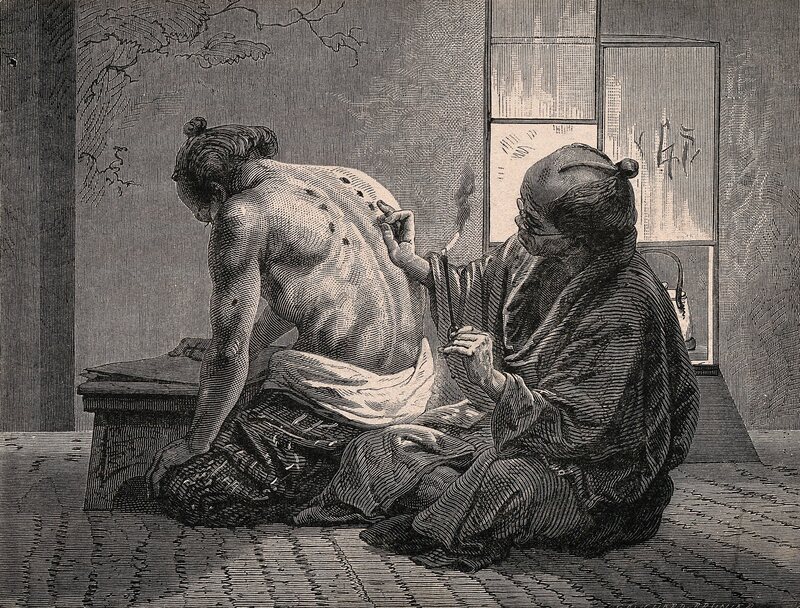

A crude machine for polishing rice. PROJECT GUTENBERG/PUBLIC DOMAIN

A crude machine for polishing rice. PROJECT GUTENBERG/PUBLIC DOMAINSince they differed mainly by diet, Takaki believed a lack of protein among lower-status sailors caused the disease. (This contradicted the most common theory at the time: that beriberi was an infectious disease caused by bacteria.) Takaki even wrangled a meeting with the emperor to discuss his theory. “If the cause of this condition is discovered by someone outside of Japan, it would be dishonorable,” he told the emperor. Change couldn’t come soon enough. In 1883, 120 Japanese sailors out of 1,000 had the disease.

Takaki also noticed that Western navies didn’t suffer from beriberi. But instituting a Western-style diet was expensive, and sailors were resistant to eating bread. An unfortunate incident, though, allowed Takaki to make his point emphatically. In late 1883, a training ship full of cadets returned from a journey to New Zealand, South America, and Hawaii. Out of the 370 cadets and crewmen, 169 had gotten beriberi, and 25 had died.

Takaki proposed an experiment. Another training ship, the Tsukuba, would set out on the exact same route. Takaki leveraged every connection he had to arrange for the Tsukuba to carry bread and meat instead of just white rice. So while the Tsukuba made its way around the world, the doctor spent sleepless nights fretting about the result: If crew members died from beriberi, he would look like a fool. Later, he told a student that he would have killed himself if his experiment failed.

A man with legs affected by beriberi stands with a walking stick. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0

A man with legs affected by beriberi stands with a walking stick. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0Instead, the Tsukuba returned to Japan in triumph. Only 14 crew members had gotten beriberi, and those men had not eaten the ordered diet. Takaki wasn’t exactly right: He believed the issue was protein rather than thiamine. But since meat was expensive, Takaki proposed giving sailors protein-filled barley, which is actually rich in thiamine. In the face of this evidence, the navy began mixing rations with barley. Within a few years, beriberi was almost totally eradicated in the navy.

But only in the navy. Takaki became navy surgeon general in 1885, yet other doctors attacked his theories and questioned his results. The sad result was that while the navy ate barley, the army ate only rice. According to Bay, the use of barley smacked of discredited traditional Japanese medicine to many Western-trained doctors. Plus, recruits were enticed into the army by promises of as much white rice as they could eat.

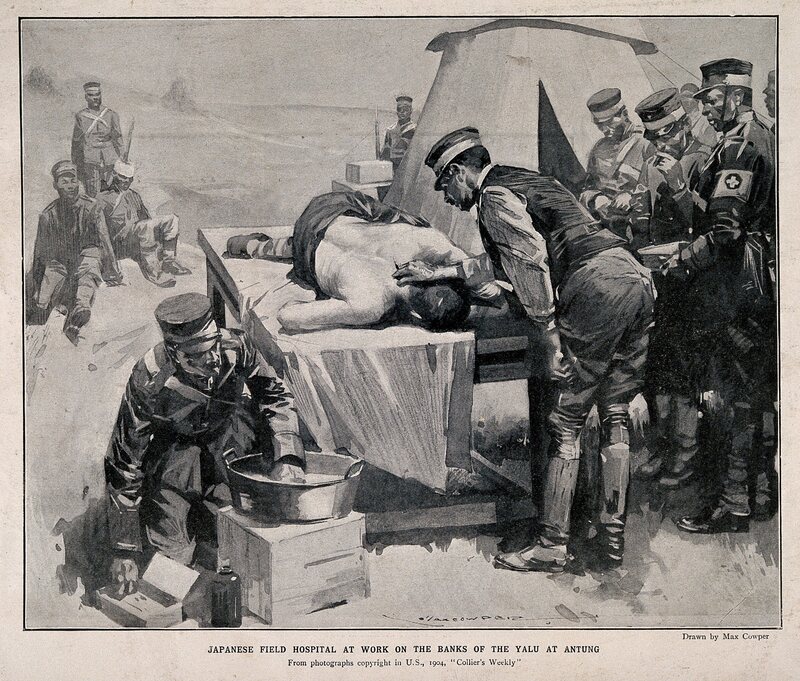

A Japanese battlefield hospital during the Russo-Japanese war. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0

A Japanese battlefield hospital during the Russo-Japanese war. WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0The result was deadly. During the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, beriberi killed 27,000 soldiers, compared to 47,000 men killed by actual war wounds. Finally, barley became a vital battlefield ration. The source of a disease that had ravaged Japan’s leadership and kneecapped the military was identified. It was the country’s staple crop, everyday meal, and cultural touchstone: simple white rice.

Vitamins had yet to be discovered, and the debate over the true cause of beriberi lingered for decades. But few could deny that Takaki had uncovered white rice’s deadly secret. Takaki, for his efforts, was made a member of the nobility in 1905. Charmingly, he was given the nickname “the Barley Baron.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our weekly email.

|