These photos don’t just display the history of a ship.

They also display those Americans who laid down their

lives to protect the USA just as they do today.

This is the USS Missouri (BB-63),

better known as “Mighty Mo”.

From a historical perspective, the USS Missouri is arguably

one of the most famous ships the world has ever seen.

Let’s begin with an over-view of some of her many feats.

The photo above is of the USS Oklahoma.

During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor,

the Oklahoma was sunk by several bombs and torpedoes.

A total of 429 crew died when the ship capsized.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Navy began building

the USS Missouri to battle Japan in the Pacific.

She was commissioned for service in 1944 and is the last

of the iconic Iowa-class battleships ever built.

In the Pacific Theater,

BB-63 fought in the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The Iowa-class battleships were literally “armed to the teeth.”

They had 9 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 Naval rifles,

which were 16 inches in diameter and fired

2,700 pound shells that could travel a distance of 20 miles.

In addition they carried 20 5"/38 “Mark 12” guns

that could hit a target 10 miles away.

For anti-aircraft protection, they had two types of guns.

There were 49 of the smaller 20 millimeter “Oerlikon” guns

and 80 larger 40mm “Borfors” guns.

From WW2, “Mighty Mo” went on to serve in the Korean War

from 1950 to 1953.

In 1984, she was modernized to carrier Tomahawk cruise

missiles along with up-dated air defense systems.

Forty-seven years after her commissioning, in 1991

the USS Missouri was modernized and sent to battle Iraq

in “Operation Desert Storm”.

The ol’ beast fired multiple Tomahawk cruise missiles at Iraqi targets.

Her final resting place came in 1998, where the Missouri has been

honored as a museum ship at Foxtrot 5 Pier on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor.

These achievements over such a long period of time are amazing

but it is one other event in which history will forever remember this ship.

On this ship the Empire of Japan officially surrendered,

bringing a final closure to World War 2.

However the real story involves none of these achievements.

In fact, this is not a story about a weapon.

This is an inspirational story about the human side of War.

One of the scariest tactics of WW2 came from the Kamikaze.

Takijiro Onishi was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy

during World War 2.

He set up the first Special Attack Unit, Kamikaze unit, near Manila

(the capital city of the Philippine Islands)

as the certainty of a U.S. invasion became unavoidable.

In his own words,

“I don’t think there would be any other certain way to carry

out the operation (to hold the Philippines),

than to put a 250 kg bomb on a Zero and let it crash into a U.S. carrier,

in order to disable her for a week.”

In total 2,800 Kamikaze attack planes were sent on their one-way missions.

They damaged 368 ships.

34 other ships were completely sunk.

MG machine gun from a crashed Kamikaze gets lodged

in the barrel of Naval Borfors gun.

The attacks accounted for over 4,800 wounded sailors and 4,900 deaths.

This was the terrifying reality of war in the Pacific.

Here is where the story begins.

Below are images of the USS Missouri battling incoming

Japanese Kamikaze “Zeroes”.

On April 11th of 1945 while fighting off incoming Kamikazes

during the battle for Okinawa, a sailor nicknamed

“Buster” Campbell was hanging out with the ship’s photographer

and caught the following unforgettable photo just before a

Zero hit the side of the ship.

The remains of the pilot were found among the wreckage.

To which the Missouri’s Captain, William Callaghan (pictured on the left),

ordered the burial of the unknown Japanese pilot the following day.

At 9am the following morning of April 12th, 1945 in waters

northeast of Okinawa, as the last major battle of World War 2

raged at both sea and ashore, the body of a Japanese pilot

is readied for burial at sea.

The pilot’s body was placed in a canvas shroud and draped

with a Japanese flag sewn by the Missouri crew.

Sailors then stood by as the flag-draped body was brought on

deck from sickbay and carried by a 6-man burial detail toward

the rail near to the point of impact.

Those present came to attention and offered a hand-salute as the

Marine rifle detail aimed their weapons skyward to render a

three-volley salute over the remains.

Then a member of the ship’s bandsmen stepped forward with

his bugle and played “Taps.”

Finally the Senior Chaplain, Commander Roland Faulk,

concluded the ceremony by saying the following,

“we commit his body to the deep”.

The burial detail then lifted the flag-draped fallen pilot over

the side and into his final resting place of the Pacific Ocean.

To this day, the bent side-railing was never replaced

in memory of the Kamikaze attack.

The lodged Kamikaze gun was from the USS Missouri crash.

These are the remains kept of the Japanese pilot.

The gold button is believed to have come from the uniform of the pilot.

In 1945, the official Allied reporting name for the

Mitsubishi A6M Zero was “Zeke” which later became

commonly known as the “Zero”.

The Kamikaze pilot had a family and a name.

This was Setsuo Ishino.

On November 26th of 1944, after the Essex-class aircraft carrier

USS Intrepid (CV-11) was struck by 2 Kamikazes which killed

6 Officers and 59 of it’s crew.

Photoed above are Kamikaze pilots in May of 1945.

They never returned, just months before the war ended.

Below is an old man named Hishashi Tezuka.

He was a kamikaze pilot that would survive because the war ended.

War is hell.

Thank you to our greatest generation.

Thank you to those out there serving today.

… the “Big Mo” is shown with a bronze of Admiral Chester Nimitz, the leader who won the war in the Pacific

--

Don't worry...be happy!

To those who say this couldn't happen today, true, not as depicted in this film. Today's charletons are more subtle but the results are just as corrupt.

These days they weaponize the I.R.S. and corrupt F.B.I. agents, are joined by a complicit MSM who quote eloquent speakers as gods.

No wonder so many "swamp dwellers" fight 'draining the swamp'!

This is a film production, but the incident really did happen. Athens is about 20 or 25 miles north Cleveland, Tenn.

Watch this short video to the end. This is the real reason why we have the 2nd Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Below are some fascinating old photographs.

A 10 x 15-foot wooden shed where the Harley-Davidson Motor Company started out in 1903

A 10 x 15-foot wooden shed where the Harley-Davidson Motor Company started out in 1903 Testing football helmets in 1912A bar in New York City, the night before prohibition began,1920Mount Rushmore Before Carving, 1920sTraffic jam in New York, 1923A quiet little job at a crocodile farm in St. Augustine, FloridaWorld economic crisis, 1929

Testing football helmets in 1912A bar in New York City, the night before prohibition began,1920Mount Rushmore Before Carving, 1920sTraffic jam in New York, 1923A quiet little job at a crocodile farm in St. Augustine, FloridaWorld economic crisis, 1929

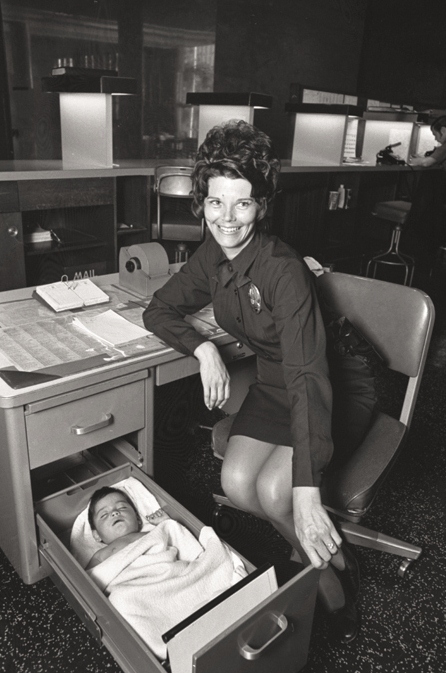

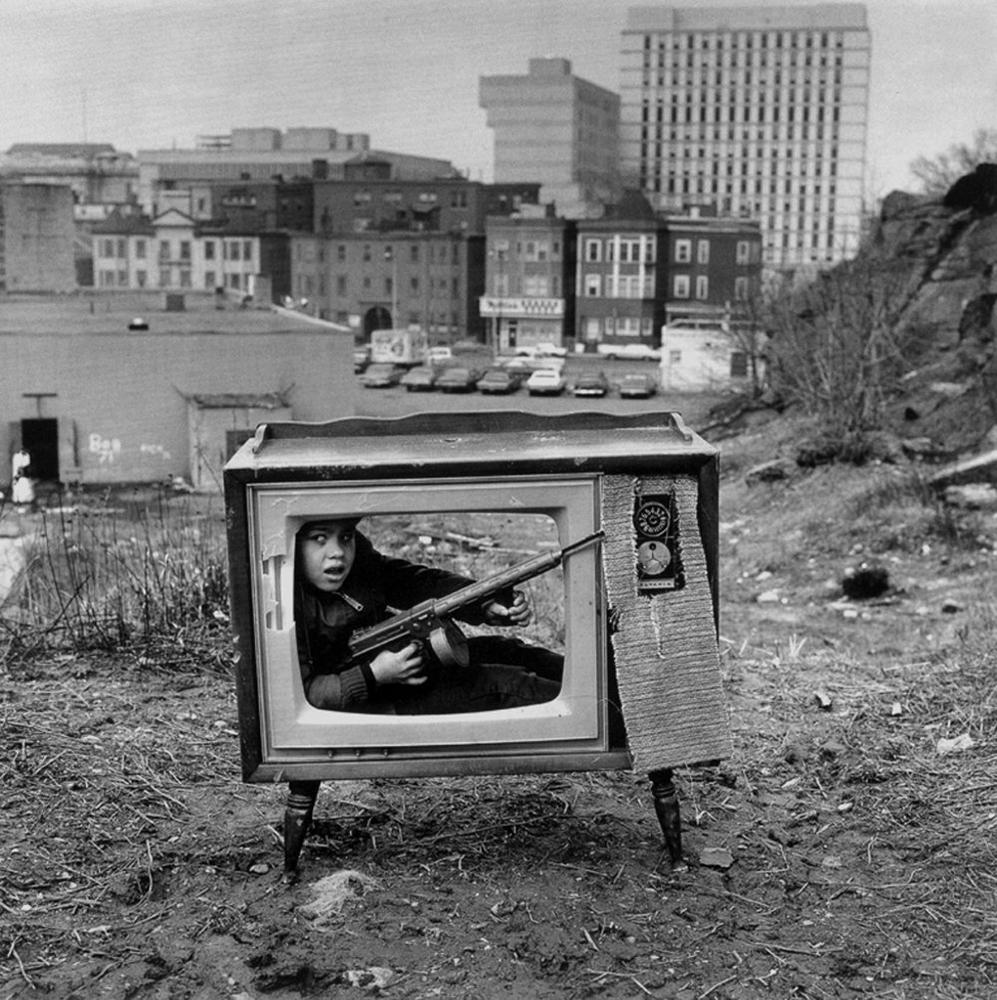

Central Park in 1930Last four couples standing at a Chicago dance marathon, ca. 1930Meeting of the Mickey Mouse Club, early 1930sConfederate and Union soldiers shake hands across the wall at the 1938 reunion for the Veterans of the Battle of GettysburgWhen they realized women were using their sacks to make clothes for their children, flour mills of the 30s started using flowered fabric for their sacks, 1939NY, Coney Island, 1940The thirty-six men needed to fly and service a B-17E in 1942Three young women wash their clothes in Central Park during a water shortage. New York, 1949 19 year-old Shigeki Tanaka was a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima and went on to win the1951 Boston Marathon. The crowd was silent as he crossed the finish line. Tanaka was notexactly a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima. When the bomb was dropped, he was athome, about 20 miles from the site. He saw a light and heard a distant rumble, but was personally unaffected by the bomb.Florida’s last Civil War veteran, Bill Lundy, poses with a jet fighter, 1955NASA scientists with their board of calculations, 1960sNew York firemen play a game after a fire in a billiard parlor, 1969An abandoned baby sleeps peacefully in a drawer at the Los Angeles Police Station, 1971Boy hiding in a TV set. Boston, 1972 by Arthur TressA spectator holds up a sign at the Academy Awards, April 1974Robert De Niro’s cab driver license. In order to get into character for the film Taxi Driver, he obtained his own hack license and would pick-up/drive customers around in New York City.Ronald Reagan wearing sweatpants on Air Force One, 1985A boxing match on board the USS Oregon in 1897

19 year-old Shigeki Tanaka was a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima and went on to win the1951 Boston Marathon. The crowd was silent as he crossed the finish line. Tanaka was notexactly a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima. When the bomb was dropped, he was athome, about 20 miles from the site. He saw a light and heard a distant rumble, but was personally unaffected by the bomb.Florida’s last Civil War veteran, Bill Lundy, poses with a jet fighter, 1955NASA scientists with their board of calculations, 1960sNew York firemen play a game after a fire in a billiard parlor, 1969An abandoned baby sleeps peacefully in a drawer at the Los Angeles Police Station, 1971Boy hiding in a TV set. Boston, 1972 by Arthur TressA spectator holds up a sign at the Academy Awards, April 1974Robert De Niro’s cab driver license. In order to get into character for the film Taxi Driver, he obtained his own hack license and would pick-up/drive customers around in New York City.Ronald Reagan wearing sweatpants on Air Force One, 1985A boxing match on board the USS Oregon in 1897

An airman being captured by Vietnamese in Truc Bach Lake, Hanoi in 1967.The airman is John McCain.

Samurai warriors taken between 1860 and 1880

A shell-shocked reindeer looks on as war planes drop bombs on Russia in 1941.

Walt Disney on the day they opened Disney StudiosThe Microsoft staff in 1978

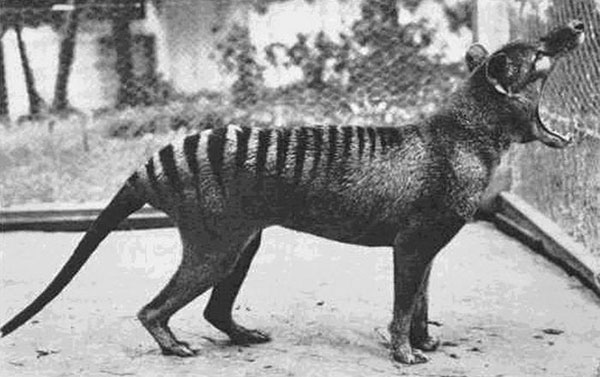

The last known Tasmanian Tiger (now extinct) photographed in 1933

German air raid on Moscow in 1941

Winston Churchill out for a swim

The London sky after a bombing and dogfight between British and German planes in 1940 Martin Luther King, Jr removes a burned cross from his yard in 1960. The boy is his son. ;Google begins.

Martin Luther King, Jr removes a burned cross from his yard in 1960. The boy is his son. ;Google begins.

Nagasaki , 20 minutes after the atomic bombing in 1945

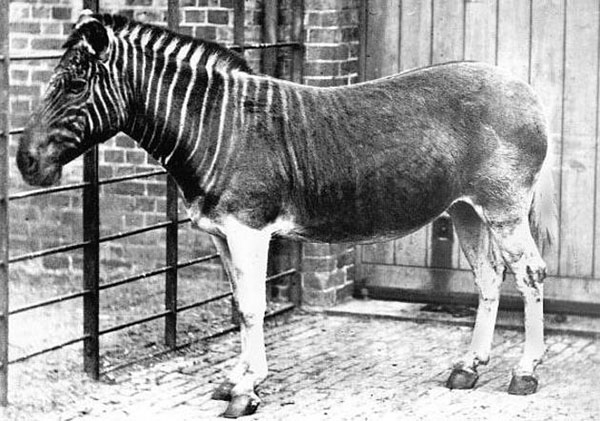

The only photograph of a living Quagga (now extinct) from 1870

Hitler’s bunker

A Japanese plane is shot down during the Battle of Saipan in 1944.

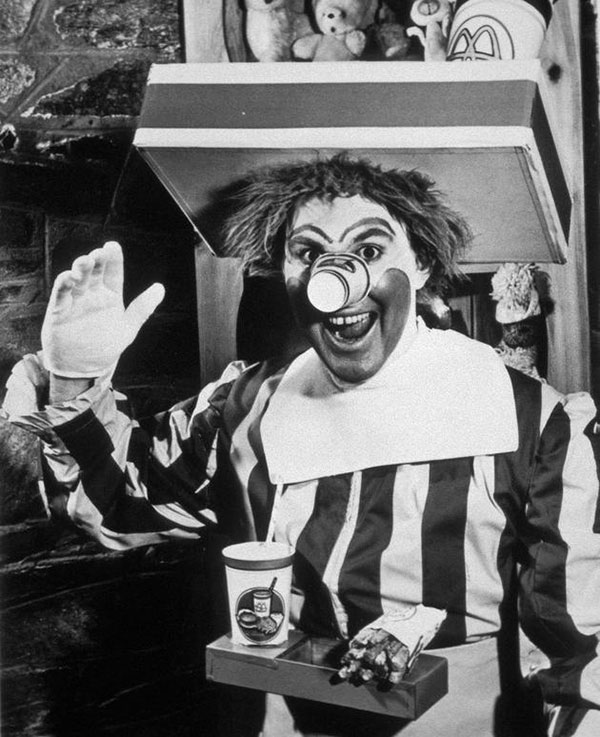

The original Ronald McDonald played by Willard Scott

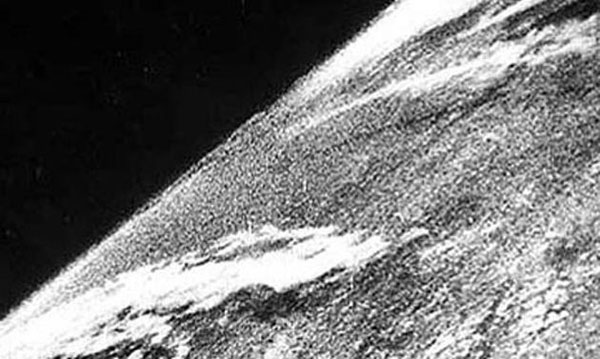

The first photo taken from space in 1946

British SAS back from a 3-month patrol of North Africa in 1943

Disneyland employee cafeteria in 1961

The first McDonalds

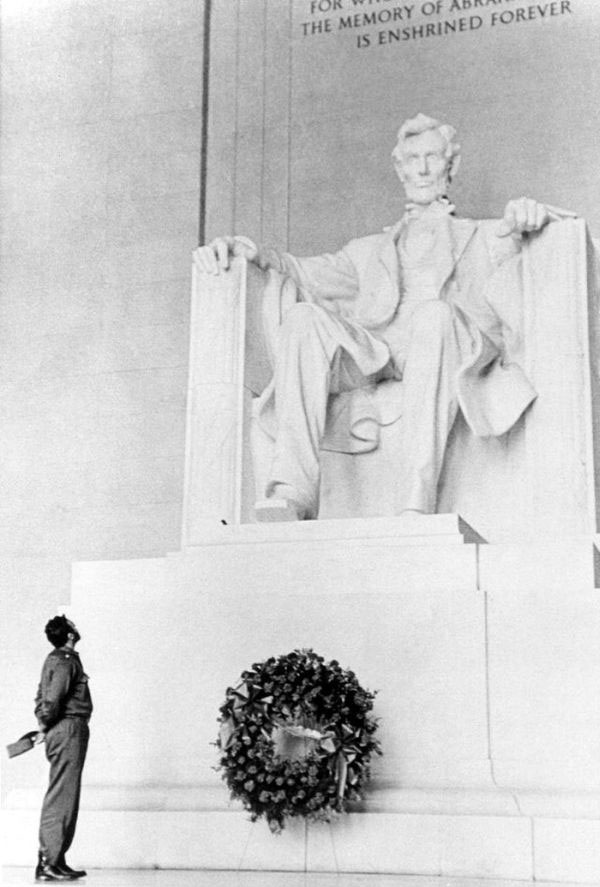

Fidel Castro lays a wreath at the Lincoln Memorial.

George S. Patton?s dog mourning his master on the day of his death.

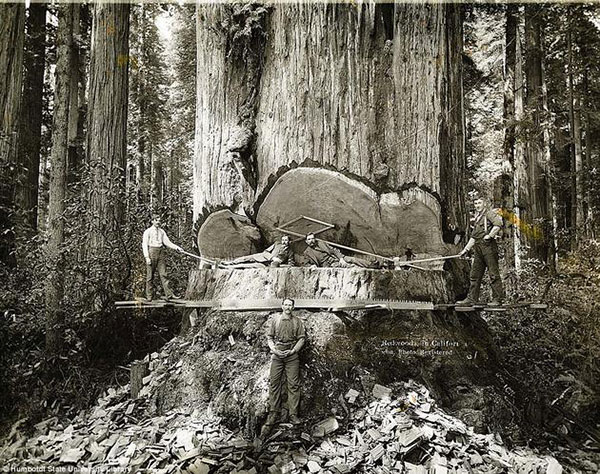

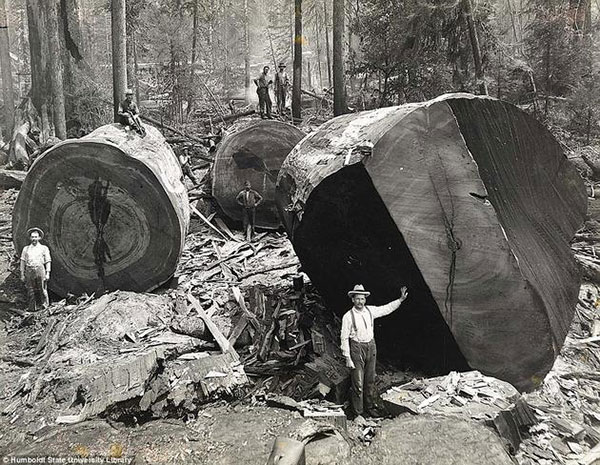

California lumberjacks working on Redwoods

Construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961

Bread and soup during the Great Depression

The 1912 World Series

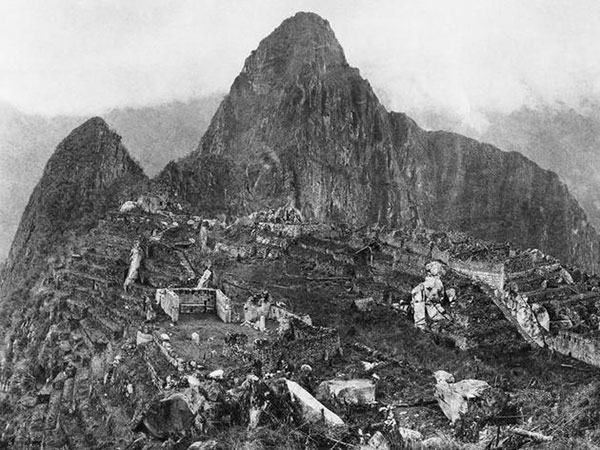

The first photo following the discovery of Machu Pichu in 1912.

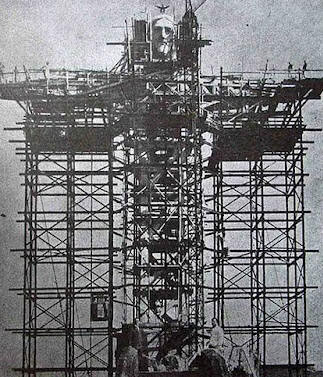

Construction of Christ the Redeemer in Rio da Janeiro, Brazil

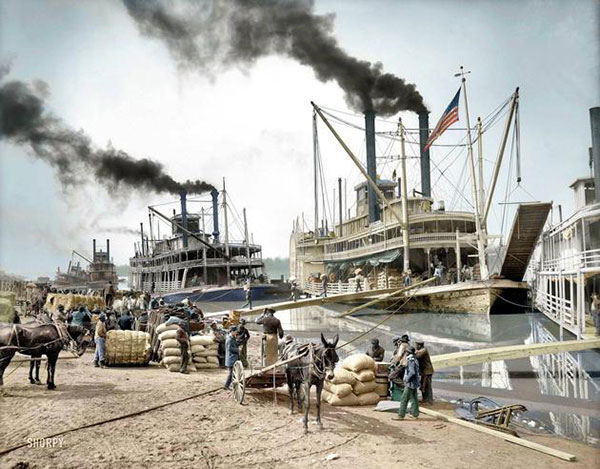

Steamboats on the Mississippi River in 1907

Leo Tolstoy telling a story to his grandchildren in 1909 ;

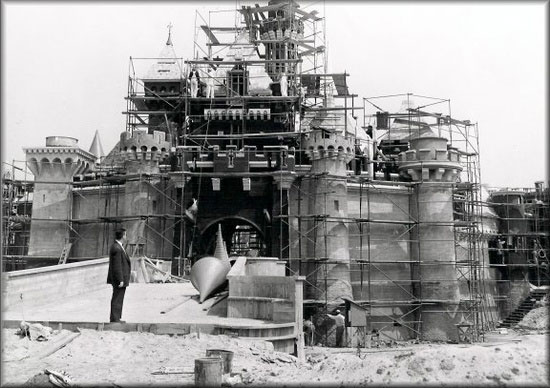

The construction of Disneyland

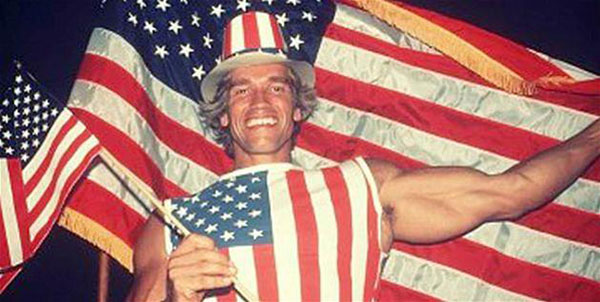

Arnold Schwarzenegger on the day he received his American citizenship

14-year-old Osama bin Laden (2nd from the right)

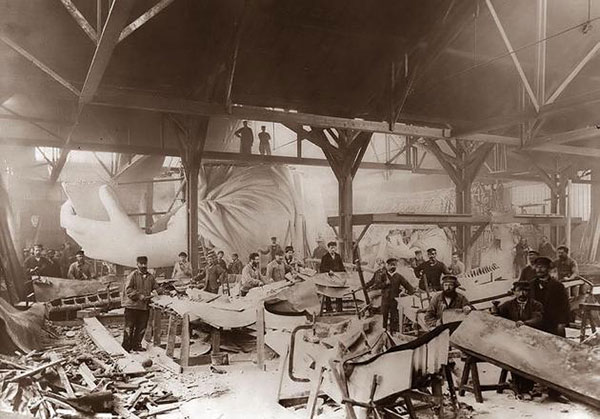

Construction of the Statue of Liberty in 1884

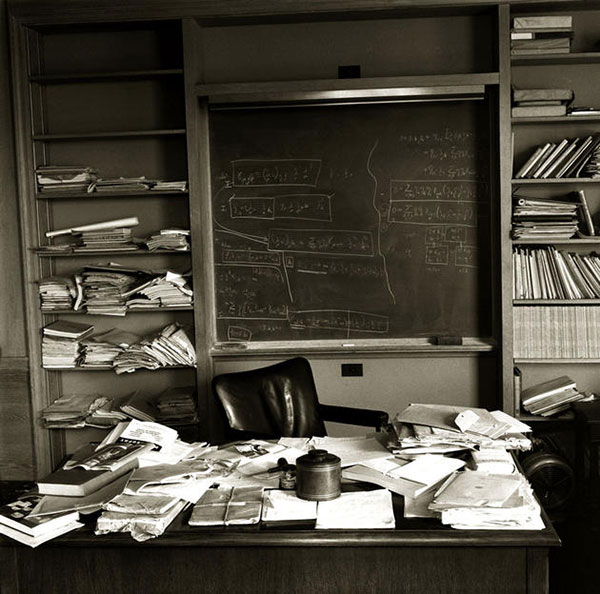

Albert Einstein’s office photographed on the day of his death

A liberated Jew holds a Nazi guard at gunpoint.

Construction of the Manhattan Bridge in 1908

Construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1888

Dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989

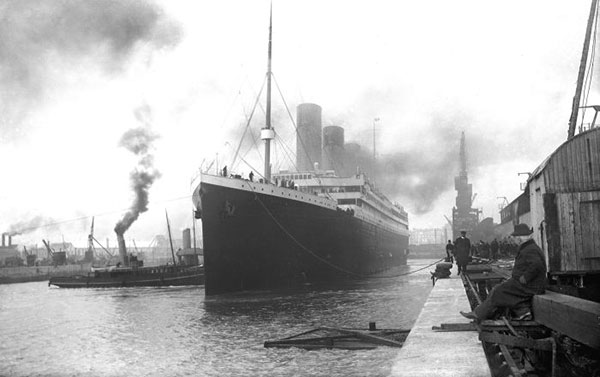

Titanic leaves port in 1912.

Adolf Hitler’s pants after the failed assassination attempt at Wolf?s Lair in 1944

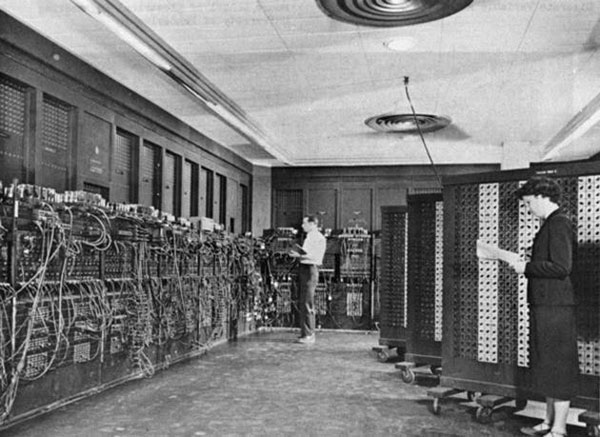

ENIAC, the first computer ever built

Brighton Swimming Club in 1863

Ferdinand Porsche showing a model of the Volkswagen Beetle to Adolf Hitler in 1935

The unbroken seal on King Tut’s tomb

Apollo 16 astronaut Charles Duke left this family photo behind on the moon in 1972.

The crew of Apollo 1 practicing their water landing in 1966. Unfortunately, all of them were killed on the launch pad in a fire.

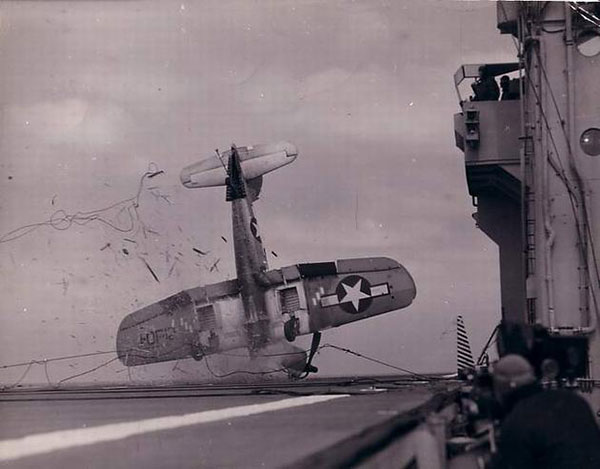

An aircraft crash on board during World War II

Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Warren G. Harding (29th president of USA ), and Harvey Samuel Firestone (founder of Firestone Tire and Rubber Co.) talking together

Notes & Comments April 2018

Fahrenheit 451 updated

What took them so long? That was our first question when we heard the latest news about the distinguished University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax. Last summer, Professor Wax created a minor disturbance in the force of politically correct groupthink when she co-authored an op-ed for The Philadelphia Inquirer titled “Paying the price for breakdown of the country’s bourgeois culture.”

What, a college professor arguing in favor of “bourgeois” values? Mirabile dictu, yes. Professor Wax and her co-author, Professor Larry Alexander from the University of San Diego, argued not only that the “bourgeois” values regnant in American society in the 1950s were beneficial to society as a whole, but also that they were potent aides to disadvantaged individuals seeking to better themselves economically and socially. “Get married before you have children and strive to stay married for their sake,” Professors Wax and Alexander advised.

Get the education you need for gainful employment, work hard, and avoid idleness. Go the extra mile for your employer or client. Be a patriot, ready to serve the country. Be neighborly, civic-minded, and charitable. Avoid coarse language in public. Be respectful of authority. Eschew substance abuse and crime.

Such homely advice rankled, of course. Imagine telling the professoriate to be patriotic, to work hard, to be civic-minded or charitable. Quelle horreur!

Wax and Alexander were roundly condemned by their university colleagues. Thirty-three of Wax’s fellow law professors at Penn signed an “Open Letter” condemning her op-ed. “We categorically reject Wax’s claims,” they thundered.

What they found especially egregious was Wax and Alexander’s observation that “All cultures are not equal.” That hissing noise you hear is the sharp intake of breath at the utterance of such a sentiment. The tort was compounded by Wax’s later statements in an interview that “Everyone wants to go to countries ruled by white Europeans” because “Anglo-Protestant cultural norms are superior.”

Can you believe it? Professor Wax actually had the temerity to utter this plain, irrefragable, impolitic truth. Everyone knows this to be the case. As William Henry argued back in the 1990s in his undeservedly neglected book In Defense of Elitism, “the simple fact [is] that some people are better than others—smarter, harder working, more learned, more productive, harder to replace.” Moreover, Henry continued, “Some ideas are better than others, some values more enduring, some works of art more universal.” And it follows, he concluded, that “Some cultures, though we dare not say it, are more accomplished than others and therefore more worthy of study. Every corner of the human race may have something to contribute. That does not mean that all contributions are equal. . . . It is scarcely the same thing to put a man on the moon as to put a bone in your nose.”

True, too true. But in a pusillanimous society terrified by its own shadow, it is one thing to know the truth, quite another to utter it in public.

For his part, Theodore Ruger, the Dean of Penn Law School, tried to have it both ways. He didn’t, on that occasion, discipline Professor Wax or seek to revoke her tenure. But he hastened to disparage her observation as “divisive, even noxious,” and to “state my own personal view that as a scholar and educator I reject emphatically any claim that a single cultural tradition is better than all others.”

What a brave man is Ted Ruger. Uriah Heep would have been proud.

There were other efflorescences of outrage directed at Professors Wax and Alexander last autumn. But since the metabolism of outrage and victimhood is voracious as well as predatory, fresh objects of obloquy were soon discovered. Attention drifted away from Amy Wax.

Until a few weeks ago, that is. At some point in March, a social justice vigilante came across an internet video of a conversation between Glenn Loury, a black, anti–affirmative action economics professor at Brown University, and Professor Wax. Titled “The Downside to Social Uplift,” the conversation, which was posted in September, revolved around some of the issues that Professor Wax had raised in her op-ed for the Inquirer. Towards the end of the interview, the painful subject of unintended consequences came up. The very practice of affirmative action, Professor Loury pointed out, entails that those benefitting from its dispensation will be, in aggregate, less qualified than those who do not qualify for special treatment. That’s what the practice of affirmative action means: that people who are less qualified will be given preference over people who are more qualified because of some extrinsic consideration—race, say, or sex or ethnic origin.

Professor Wax agreed and noted that one consequence of this was that those admitted to academic programs through affirmative action often struggle to compete. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a black student graduate in the top quarter of the class,” Professor Wax said, “and rarely, rarely in the top half.” Professor Wax also observed that the Penn Law Review had an unpublicized racial diversity mandate.

Uh-oh. It took several months for the censors to get around to absorbing this comment. But last month they finally did and the result was mass hysteria. From Ghana to Tokyo to Israel, students associated with Penn Law School were furiously trading emails, tweets, and other social media bulletins about Amy Wax. The university’s Black Law Students Association, whose president, Nick Hall, was instrumental in publicizing the video, went into a swivet. What, they demanded of Dean Ruger, was he going to do about Professor Wax’s outrageous comments?

In a word, capitulate. Then preen. Dean Ruger announced that Professor Wax would henceforth be barred from teaching any mandatory first-year courses. “It is imperative for me as dean to state,” he thundered, “that . . . black students have graduated in the top of the class at Penn Law, and the Law Review does not have a diversity mandate.” Did he offer any data to back that up? No. Perhaps Penn doesn’t keep track. But Dean Ruger may wish to consult a study published in the Stanford Law Review in 2004 which showed that in the most elite law schools, 52 percent of first-year black students pooled in the bottom tenth of their class, compared to 6 percent of whites. Only 8 percent of first-year black students were in the top half of their class.

Lack of data, however, is no impediment to declaring one’s higher virtue while simultaneously caving in to the atavistic forces of political correctness. Amy Wax, intoned Dean Ruger, is “protected by Penn’s policies of free and open expression as well as academic freedom.” Nevertheless, she will be treated as a toxic personality, too dangerous for Penn’s tender shoots embarking on a career in law. “In light of Professor Wax’s statements,” Dean Ruger wrote in a community-wide email,

black students assigned to her class . . . may reasonably wonder whether their professor has already come to a conclusion about their presence, performance, and potential for success in law school and thereafter. They may legitimately question whether the inaccurate and belittling statements she has made may adversely affect their learning environment and career prospects. . . . More broadly, this dynamic may negatively affect the classroom experience for all students regardless of race or background.

As Jason Richwine noted in a column for National Review, Dean Ruger’s protest is “almost Orwellian in its blame-shifting.” All of the issues he lists “are the direct result of Penn’s affirmative-action policies. Those policies generate a racial skills gap in Penn’s first-year law class, and Professor Wax has merely voiced what every rational observer already knows.” Moreover, grading of first-year students at Penn is blind: professors do not know which grade is assigned to which student.

Doubtless Dean Ruger hoped that by scapegoating Amy Wax he would effectively mollify the beast of political correctness. Not likely. As could have been predicted, his capitulation and nauseating Two-Minutes-Hate display of politically correct grandiosity merely sharpened the appetite of the racial grievance mongers. Dean Ruger publicly castigated and in effect demoted Amy Wax. But that was not enough for Asa Khalif, a leader of Black Lives Matter Pennsylvania, who is demanding that she be fired outright. Indeed, he told The Philadelphia Tribune that Penn has one week to comply. “None of what this racist is doing is new to anyone familiar with her,” Khalif said. “Many people have known about her for years. Not just black and brown people, but people who don’t believe she can fairly grade or teach people who don’t look like her. . . . We are unwavering in our one demand that she be fired.”

As we write, L’affaire Wax is still unfolding. Who knows to what lengths Mr. Khalif and his Black Lives Matter thugs are willing to go? Who knows what ecstasies of groveling condemnation Dean Ruger or other Penn administrators may indulge? One thing, however, is clear. The truth is a dispensable commodity at our elite colleges and universities. When it clashes with the imperatives of political correctness, the truth loses. Like the firemen in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, most of those populating the higher education establishment are busy destroying the very things they had, once upon a time, been trained to cherish and protect.