https://www.shootingillustrated.com/content/after-the-shooting-stops/

From a YouTube comment:

"In certain circles, the 3 Gorges Dam is known as the Taiwanese Independence Dam. As soon as China made the dam, they essentially made Taiwan a nuclear power, since most of Taiwan's Yun Feng missiles are said to be targeted on the dam, giving Taiwan the ability to destroy at least 3 major Chinese cities."

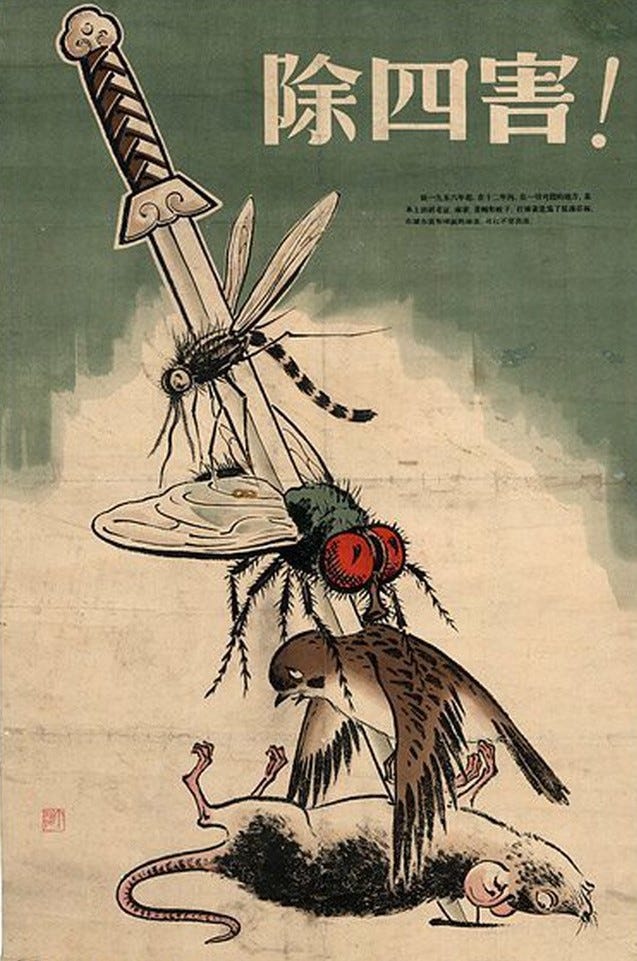

The killing of tree sparrows backfired and resulted in the deaths of 55 million Chinese

“B

irds are public animals of capitalism,” declared the communist government of China under Mao Zedong (1893 -1976). In 1958, claiming sparrows eat the proletariat’s hard work, the Chinese government ordered the complete extermination of the sparrows.Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks killed. The sparrows went nearly extinct.

The Four Pests campaign

As part of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward initiative from 1958 to 1962, the Chinese eliminated rats, flies, mosquitos, and sparrows.

These four animals were accused of:

- mosquitos were responsible for malaria

- rodents caused plague

- flies were a nuisance in general

- Eurasian tree sparrows ate grain and fruit

Over the period of three years, approximately one billion sparrows, 1.5 billion rats, 100 million kilograms of flies, and 11 million kilograms of mosquitos were killed throughout China.

The Chinese total war on sparrows

The Chinese officials believed each sparrow ate 4.5 kilograms (9.9 pounds) of grain per year.

Mao Zedong claimed sparrows were the enemies of communism and hindered the economic development of China.

In 1958, the Chinese government declared a war on sparrows.

For multiple days in a row, millions of Chinese took part in the hunt for sparrows.

Besides shooting sparrows, destroying their nests and eggs, and raising an army of scarecrows, the Chinese used a very ingenious method to kill the birds — noise.

By hitting on pots and pans, screaming slogans such as “Long live the great Mao”, and waving rags attached to long poles, they prevented sparrows from resting in their nests, which caused them to drop dead from exhaustion.

Sparrows can’t stay in the air for over fifteen minutes without resting.

“I remembered a day when the entire population did nothing but use gongs and pots and all sorts of other objects suitable for making a noise on the streets and in running about the yards to startle the sparrows. There had been so much noise all day that the birds had nowhere to settle and finally fell dead from the sky.”

— Kuan Yu-Chien, a Chinese writer

Schools, working brigades, and government agencies that killed the most pests received recognition and rewards.

Some sparrows found refuge in embassies

Interestingly, sparrows found refuge near the embassies. For example, the Polish embassy in Beijing refused to kill the sparrows.

Consequently, the Chinese surrounded the building with drums and played on them for straight two days.

Sparrows took to the air and flew around until they dropped dead from exhaustion.

The Poles had to use shovels to clean all the dead sparrows.

The extermination of sparrows caused a terrible environmental disaster

The large-scale hunt nearly eradicated sparrows, which caused a huge imbalance in nature.

Yes, sparrows do eat grain, but they also feed on locusts and other insects, such as the common asparagus beetle (Crioceris asparagi).

The extinction of sparrows led to the increased populations of insects and locusts, which in turn destroyed the crops.

The combination of the extermination of sparrows, droughts, floods, and ineffective government policies resulted in the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-61, the deadliest famine in human history.

According to some sources, 55 million Chinese died because of famine.

By April 1960, the Chinese government stopped its war on sparrows and redirected efforts to the extermination of bedbugs.

In an ironic twist of fate, the Chinese government had to buy 250,000 sparrows from the Soviet Union to speed up the repopulation of these useful birds.

Conclusion

Not only the Chinese, but all of humanity tries to control and shape the environment. We forget we are now owners of the planet Earth; we are merely renting it. We are at Earth’s mercy.

” Make the high mountain bow its head, make the river yield the way.”

— Mao Zedong, the founder of communist China

Yes, we can lower mountains and re-route rivers, but we suffer also the consequences. Especially if we lack an understanding of the consequences of our actions.

The killing of one billion sparrows massively backfired and resulted in the deaths of 55 million Chinese people.