- Inside Japan’s Plan To Bomb America With Bubonic Plague During World War II

In 1945, Japan developed a plot for mass death in America via biological warfare under the innocuous title "Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night." Here's why the plan failed miserably.

Xinhua via Getty ImagesUnit 731 personnel conduct a bacteriological test on a child in Nongan County of northeast China’s Jilin Province. November 1940.

The story of World War II has been retold so many times that it might be easy to forget that some of the war’s more obscure horrors still remain unknown to the general public. For example, few know that in the final year of the war, Japan developed a plan for mass death via biological warfare under the title “Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night.”

With microbiologist and general Shiro Ishii at the helm, Japan’s chemical warfare research division Unit 731 came terrifyingly close to crop-dusting the U.S. with fleas infected with the bubonic plague.

The dress rehearsal for peppering American landscapes with a medieval disease had already been conducted by Japan against one of its closest neighbors: China.

The court transcripts of the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials in 1949, in which 12 members of the Japanese Kwantung Army were tried as war criminals, revealed as much — and publicized the war crime’s chilling details:

“The fleas were intended for the purpose of preserving the [plague] germs, of carrying them, and of directly infecting human beings.”

Unit 731 Experiments On Chinese People

Wikimedia CommonsGeneral Shiro Ishii lived his post-war life in peace by garnering U.S. immunity in exchange for the experimental research he had amassed.

After the Geneva Convention banned germ warfare in 1925, Japanese officials reasoned that such a prohibition only confirmed how potent a weapon it would be. This led to Japan’s biological weapons program in the 1930s and the army’s biological warfare division, Unit 731.

It didn’t take long for the Japanese army to subject Chinese civilians to their cruel experiments. As Japan occupied large swaths of China in the early 1930s, the army settled in Harbin near Manchuria — evicting eight villages there — and built the infamous Harbin facility. What occurred there was some of the most inhumane activity of the 20th century.

Wikimedia CommonsUnit 731’s Harbin facility was built on Manchurian land conquered by Japan.

The macabre research included locking subjects into chambers and applying pressurized air until their eyes burst from their sockets, or determining how much G-force was required to induce death.

Former Unit 731 medical worker Takeo Wano said he witnessed a man pickled in a six-foot-high glass jar — after being vertically cut into two pieces. There were other jars that contained heads, feet, and even entire bodies, sometimes labeled by the victim’s nationality.

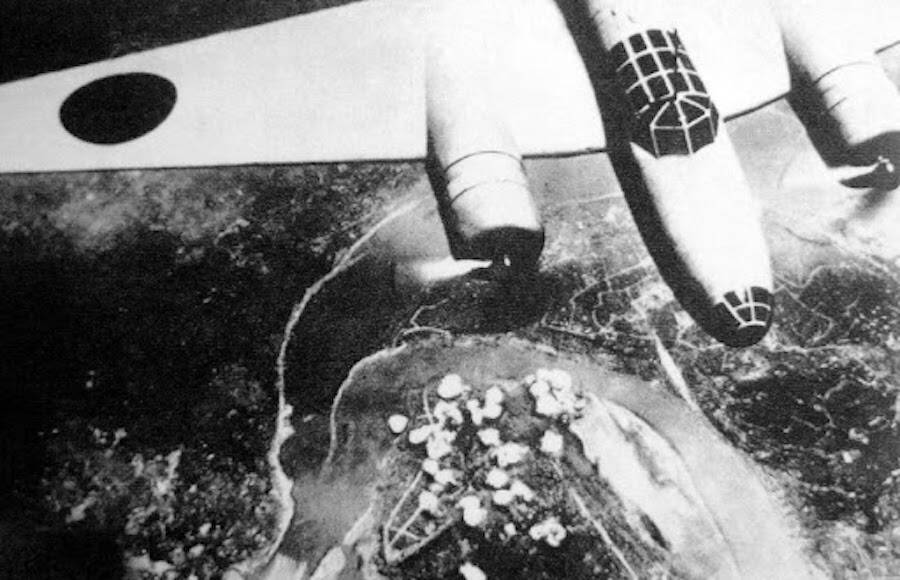

By October 1940, Japanese forces had turned to plague warfare. They bombarded Ningbo in eastern China and Changde in north-central China with infected fleas. Qiu Mingxuan, who survived the bombing as a nine-year-old and later become an epidemiologist, estimated that at least 50,000 citizens were killed due to these bombardments.

Wikimedia CommonsSpecial Naval landing forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy prepare to advance during the Battle of Shanghai in August 1937 — with gas masks firmly in place.

“I can still remember the panic among the people,” said Mingxuan. “Everybody kept their doors closed and was afraid to go out. The stores were closed down. The schools were closed down. But by December, the Japanese airplanes came to drop bombs almost every day. We couldn’t keep the quarantine area closed. The people inside ran to the countryside, carrying the plague germs with them.”

On the heels of such a resounding success, Unit 731’s death-dealing concoction was ready to make the long trip across the Pacific.

Operation Cherry Blossoms At Night

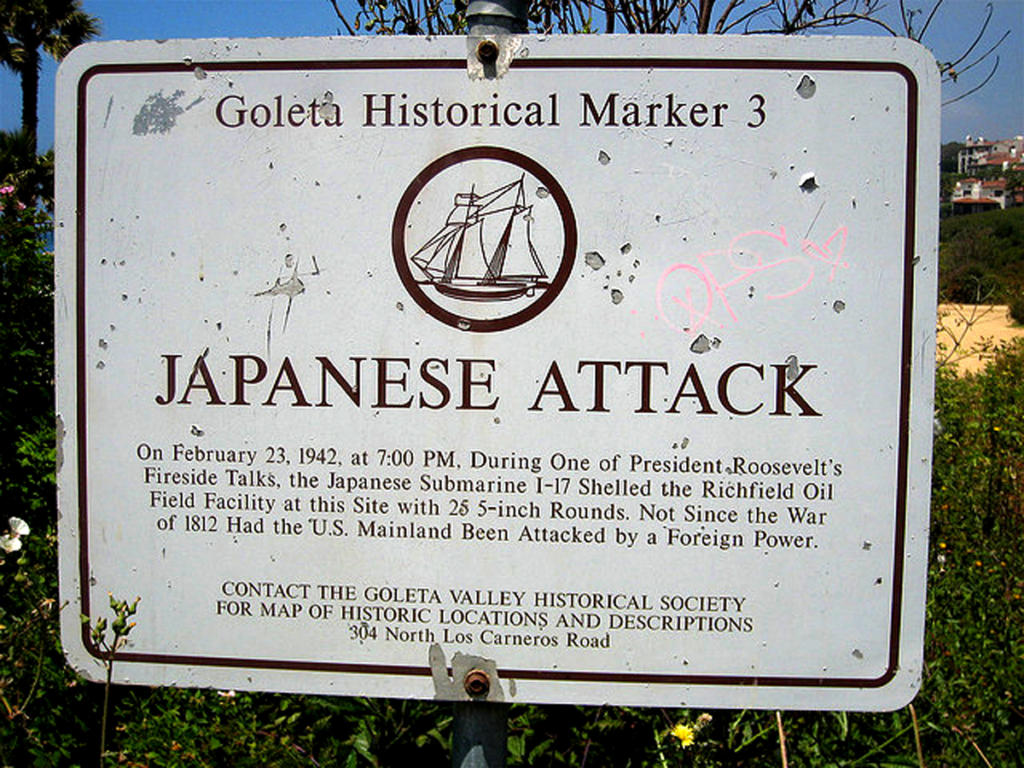

Japan initially planned to launch large balloon bombs that would ride the jet stream to America. They were successful in delivering around 200 of them. The bombs killed seven Americans, though the U.S. government censored reports of the killings.

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night would have seen kamikaze pilots strike first against California. The instructor for new Unit 731 recruits, Toshimi Mizobuchi, planned to take 20 of the 500 new troops who arrived in Harbin in 1945 to the southern California coast on a submarine. They would then man an onboard plane and fly it to San Diego.

Thousands of plague-riddled fleas would be deployed as a result, dropped by the troops who would take their own lives by crashing onto American soil.

The operation was set for Sept. 22, 1945. For surviving witness and chief of the attack force, Ishio Obata, the mission was so gut-churning that it was difficult to recall decades later.

Xinhua via Getty ImagesUnit 731 researchers conduct bacteriological experiments on captive child subjects in Nongan County of northeast China’s Jilin Province. November 1940.

“It is such a terrible memory that I don’t want to recall it,” he said. “I don’t want to think about Unit 731. Fifty years have passed since the war. Please let me remain silent.”

Fortunately, the Cherry Blossoms plot never came to fruition.

The Failure Of The Plot Against America

One Japanese Navy specialist claimed the Navy would have never approved this mission, especially in the latter half of 1945. By that point, protecting Japan’s most valuable islands was far more important than launching attacks on the United States.

By Aug. 9, 1945, the country started blowing up as much evidence of their Unit 731 experimentation as humanly possible. Nonetheless, its history survived — partly due to the United States granting General Shiro Ishii immunity in exchange for his research.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Japanese soldiers bombed Chongqing from 1938 to 1943.

There’s still an open debate on how close Cherry Blossoms at Night was to being executed. What is known is that during a critical meeting in July 1944 it was General Hideki Tōjō who rejected using germ warfare against the United States.

He recognized that Japan’s defeat was most likely imminent and that the use of bioweapons would only escalate America’s retaliation.

Before he died of throat cancer in 1959, Shiro Ishii lived out his life in peace. Many of the men below him in the chain of command were later elevated to higher places of power in Japan’s government. One became Tokyo’s governor, another the head of the Japan Medical Association.

When asked about their actions decades later, many of the men rationalized their wartime research. For the Unit 731 medic who cut one Chinese prisoner into pieces without anesthesia, the logic was all quite simple.

“Vivisection should be done under normal circumstances,” he said. “If we’d used anesthesia, that might have affected the body organs and blood vessels that we were examining. So we couldn’t have used anesthetic.”

H.S. WongA crying baby in the ruins of Shanghai’s South Station after a devastating Japanese bombing on Aug. 28, 1937.

When asked how these experiments could have possibly included children, he was just as blunt.

“Of course there were experiments on children,” he said. “But probably their fathers were spies. There’s a possibility this could happen again. Because in a war, you have to win.”

Similar reasoning could have seen Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night brought to its full completion. Ultimately, it may have only been Hideki Tōjō’s intervention that prevented the mass death of American civilians. But when his turn finally came, no one intervened to save Tōjō.

A little over a week after Japan’s surrender, Tōjō attempted suicide with an American pistol. His life was saved with a transfusion of American blood. Then it was taken three years later, when Hideki Tōjō was hung by an international tribunal for war crimes.

After learning about Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, read about four of the most evil science experiments ever performed. Then, learn about Japan’s World War II-era reign of terror.

His Parachute Got Stuck on the Plane’s Wheel and He Was Suspended in Midair with Little Chance of Survival—Then Another Plane Came to His Rescue

Almost 80 years after it unfolded in the sky over San Diego, a nearly impossible rescue mission remains one of the most daring feats in aeronautical history.

It began like any other May morning in California. The sky was blue, the sun hot. A slight breeze riffled the glistening waters of San Diego Bay. At the naval airbase on North Island, all was calm.

At 9:45 a.m., Walter Osipoff, a sandy-haired 23-year-old Marine second lieutenant from Akron, Ohio, boarded a DC-2 transport for a routine parachute jump. Lt. Bill Lowrey, a 34-year-old Navy test pilot from New Orleans, was already putting his observation plane through its paces. And John McCants, a husky 41-year-old aviation chief machinist’s mate from Jordan, Montana, was checking out the aircraft that he was scheduled to fly later. Before the sun was high in the noonday sky, these three men would be linked forever in one of history’s most spectacular midair rescues.

Osipoff was a seasoned parachutist, a former collegiate wrestling and gymnastics star. He had joined the National Guard and then the Marines in 1938. He had already made more than 20 jumps by May 15, 1941.

That morning, his DC-2 took off and headed for Kearney Mesa where Osipoff would supervise practice jumps by 12 of his men. Three separate canvas cylinders, containing ammunition and rifles, were also to be parachuted overboard as part of the exercise.

Nine of the men had already jumped when Osipoff, standing a few inches from the plane’s door, started to toss out the last cargo container. Somehow, the automatic-release cord of his backpack parachute became looped over the cylinder and his chute was suddenly ripped open. He tried to grab hold of the quickly billowing silk but, the next thing he knew, he had been jerked from the plane—sucked out with such force that the impact of his body ripped a 2.5-foot gash in the DC-2’s aluminum fuselage.

Instead of flowing free, Osipoff’s open parachute now wrapped itself around the plane’s tail wheel. The chute’s chest strap and one leg strap had broken; only the second leg strap was still holding—and it had slipped down to Osipoff’s ankle. One by one, 24 of the 28 lines between his precariously attached harness and the parachute snapped. He was now hanging some 12 feet below and 15 feet behind the tail of the plane. Four parachute shroud lines twisted around his left leg were all that kept him from being pitched to the earth.

Dangling there upside down, Osipoff had enough presence of mind to not try to release his emergency parachute. With the plane pulling him one way and the emergency chute pulling him another, he realized that he would be torn in half. Conscious all the while, he knew that he was hanging by one leg, spinning and bouncing—and he was aware that his ribs hurt. He did not know then that two ribs and three vertebrae had been fractured.

Inside the plane, the DC-2 crew struggled to pull Osipoff to safety but they could not reach him. The aircraft was starting to run low on fuel but an emergency landing with Osipoff dragging behind would certainly smash him to death. And, pilot Harold Johnson had no radio contact with the ground.

To attract attention below, Johnson eased the transport down to 300 feet and started circling North Island. A few people at the base noticed the plane coming by every few minutes but they assumed that it was towing some sort of target.

Meanwhile, Bill Lowrey had landed his plane and was walking toward his office when he glanced upward. He and John McCants, who was working nearby, saw at the same time the figure dangling from the plane. As the DC-2 circled once again, Lowrey yelled to McCants, “There’s a man hanging on that line. Do you suppose we can get him?” McCants answered grimly, “We can try.”

Lowrey shouted to his mechanics to get his plane ready for takeoff. It was an SOC-1, a two-seat, open-cockpit observation plane less than 27 feet long. Recalled Lowrey afterward, “I didn’t even know how much fuel it had.” Turning to McCants, he said, “Let’s go!”

Lowrey and McCants had never flown together before but the two men seemed to take it for granted that they were going to attempt the impossible. “There was only one decision to be made,” Lowrey later said quietly, “and that was to go get him. How, we didn’t know. We had no time to plan.”

Nor was there time to get through to their commanding officer and request permission for the flight. Lowrey simply told the tower, “Give me a green light. I’m taking off.” At the last moment, a Marine ran out to the plane with a hunting knife—for cutting Osipoff loose—and dumped it in McCants’s lap.

As the SOC-1 roared aloft, all activity around San Diego seemed to stop. Civilians crowded rooftops, children stopped playing at recess, and the men of North Island strained their eyes upward. With murmured prayers and pounding hearts, the watchers agonized through every move in the impossible mission.

Within minutes, Lowrey and McCants were under the transport, flying at 300 feet. They made five approaches but the air proved too bumpy to try for a rescue. Since radio communication between the two planes was impossible, Lowrey hand-signaled Johnson to head out over the Pacific where the air would be smoother and they climbed to 3,000 feet. Johnson held his plane on a straight course and reduced speed to that of the smaller plane—100 miles an hour.

Lowrey flew back and away from Osipoff but level with him. McCants, who was in the open seat in back of Lowrey, saw that Osipoff was hanging by one foot and that blood was dripping from his helmet. Lowrey edged the plane closer with such precision that his maneuvers jibed with the swings of Osipoff’s inert body. His timing had to be exact so that Osipoff did not smash into the SOC-1’s propeller.

Finally, Lowrey slipped his upper left wing under Osipoff’s shroud lines and McCants, standing upright in the rear cockpit—with the plane still going 100 miles an hour 3,000 feet above the sea—lunged for Osipoff. He grabbed him at the waist and Osipoff flung his arms around McCants’s shoulders in a death grip.

McCants pulled Osipoff into the plane but, since it was only a two-seater, the next problem was where to put him. As Lowrey eased the SOC-1 forward to get some slack in the chute lines, McCants managed to stretch Osipoff’s body across the top of the fuselage with Osipoff’s head in his lap.

Because McCants was using both hands to hold Osipoff in a vise, there was no way for him to cut the cords that still attached Osipoff to the DC-2. Lowrey then nosed his plane inch by inch closer to the transport and, with incredible precision, used his propeller to cut the shroud lines. After hanging for 33 minutes between life and death, Osipoff was finally free.

Lowrey had flown so close to the transport that he’d nicked a 12-inch gash in its tail. But now the parachute, abruptly detached along with the shroud lines, drifted downward and wrapped itself around Lowrey’s rudder. That meant that Lowrey had to fly the SOC-1 without being able to control it properly and with most of Osipoff’s body still on the outside. Yet, five minutes later, Lowrey somehow managed to touch down at North Island and the little plane rolled to a stop. Osipoff finally lost consciousness—but not before he heard sailors applauding the landing.

Later on, after lunch, Lowrey and McCants went back to their usual duties. Three weeks later, both men were flown to Washington, D.C., where Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox awarded them the Distinguished Flying Cross for executing “one of the most brilliant and daring rescues in naval history”.

Osipoff spent the next six months in the hospital. The following January, completely recovered and newly promoted to first lieutenant, he went back to parachute jumping. The morning he was to make his first jump after the accident, he was cool and laconic, as usual. His friends, though, were nervous. One after another, they went up to reassure him. Each volunteered to jump first so he could follow.

Osipoff grinned and shook his head. “The hell with that!” he said as he fastened his parachute. “I know damn well I’m going to make it.” And he did.

This article first appeared in the May 1975 edition of Reader’s Digest.