Today's selection -- from Where The Wild Things Were by William Stolzenburg. Charles Elton, Georgyi Frantsevitch Gause, Nelson G. Hairston, Frederick E. Smith, and Lawrence B. Slobodkin expanded our understanding of the world’s ecology:

"In 1927, his mind straining at the seams from three summers at Spitsbergen, Elton sat down at his desk and released the floodgates. In a ninety-day burst of creative fervor he wrote a two-hundred-page book, published simply as Animal Ecology. Eighty years later, the elegant little volume remains a standard on reading lists and bookshelves of students and professors of ecology.

"In clear bold tones and basic English, Animal Ecology frames the questions, and a good many of the answers, that still occupy the major discussions of modem science. Gems of Elton's prescience can be found on nearly every page of Animal Ecology. But one could start by flipping to chapter 5, 'The Animal Community,' and immediately find the essence of Elton's ecological perspective. There at the head of the page it is laid out in three Chinese proverbs:

'The large fish eat the small fish; the small fish eat the water insects; the water insects eat plants and mud.'

'Large fowl cannot eat small grain.'

'One hill cannot shelter two tigers.'

"This was Elton's way of introducing several of the most important concepts in the field of community ecology. It is a chapter that begins with Elton studiously watching an anthill and finishes with a lion killing zebras. And in between those poles, he boils down the whole of animal society to a word, food:

Animals are not always struggling for existence, but when they do begin, they spend the greater part of their lives eating ... Food is the burning question in animal society, and the whole structure and activities of the community are dependent upon questions of food-supply.

"Elton's Animal Ecology draws heavily on his apprenticeship in Spitsbergen. He had ultimately discovered order in the freewheeling Arctic assemblage, and it had come to his mind in familiar shapes and constructions. He saw the sun's energy linked to the greenery of tundra plants to the feathers of ptarmigan to the muscle of Arctic fox. It was simple enough: Plants eat sunlight, herbivores eat plants, carnivores eat herbivores, 'and so on,' he wrote, 'until we reach an animal which has no enemies.' life was linked in chains of food.

|

| Charles Sutherland Elton |

"One could find a welter of such chains, even in the skeleton crew of species that epitomized Spitsbergen. Here Elton included a hand-drawn sketch. In what otherwise resembles the electrical diagram of a circuit board, Elton's lines and arrows run this way and that, connecting boxes labeled guillemots and protozoa, dung. spider, plants, worms, geese, purple sandpiper and ptarmigan, mites, moss, seals, polar bear, more dung, more arrows, all arrows eventually leading to the Arctic fox.

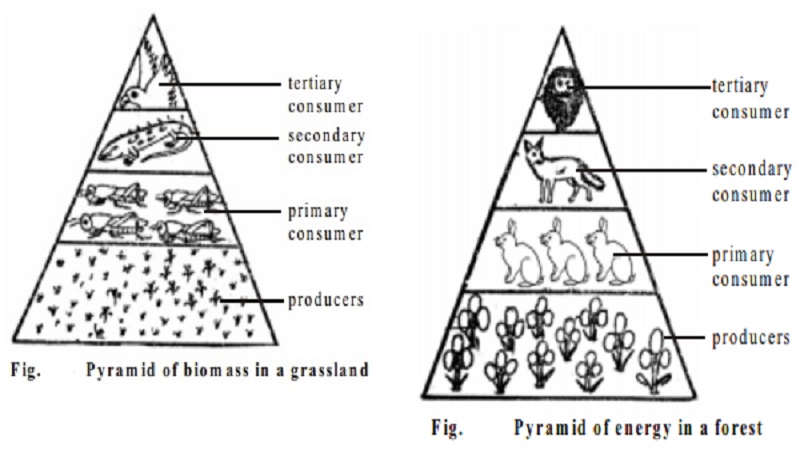

"The chains are intertwined, crisscrossing and connecting, forming what Elton had come to think of as a 'food-cycle,' what his descendants today call a food web. Elton, in his fascination with numbers, started adding them to that web: Roughly how many plants and plankton at this end of the chain, how many foxes and bears at that end? With the numbers, his web had gained a third dimension, and its shape now took the form of a pyramid.

"Elton's pyramid is a narrowing progression in this community of life, founded on a broad, numerous base of plants and photosynthetic plankton-harvesters of the sun's energy, primary producers of food. From there it steps up to a substantially more narrow layer of herbivorous animals cropping their share from below, and so on up to yet a smaller tier of carnivores feeding on the plant-eaters. Perched loftily at the apex are the biggest, rarest, topmost predators, those capable of eating all, and typically eaten by none. In the prolific plains of the Serengeti, that predator would be the African lion; in the stingy tundra of Spitsbergen, that predator happens to be a scrappy little fox, 'the apex of the whole terrestrial ecological pyramid in the Arctic.' Elton's geometric perspective on life would soon become one of the tenets of ecology, and to this day is known as the Eltonian pyramid.

"Animal Ecology is where the food chains that Elton realized in the guano gardens of Spitsbergen, where the pyramid of numbers he saw spreading beneath the Arctic fox, are set down as principles for all life on Earth.

"Along the way, Elton also discussed the importance of body size with regard to the act of eating and being eaten -- stating again the obvious observation whose importance had somehow escaped so many before him. 'There are very definite limits, both upper and lower, to the size of food which a carnivorous animal can eat ... Spiders do not catch elephants in their webs, nor do water scorpions prey on geese.' He also gave new life and meaning to the word 'niche,' through his own definition: An animal's 'place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies.'

"The Chinese may have offered the original inklings on animal ecology, but it was Elton who built a pyramid out of them. With his niches, his food chains, his pyramids, Elton gave his fellow ecologists homework assignments for the coming century.

"It was easy enough to see, with the help of Elton's timely reminder, that life was stacked in a pyramid of numbers. But what controlled those numbers? 'What prevents the animals from completely destroying the vegetable and possibly other parts of the landscape,' asked Elton. 'That is, what preserves the balance of numbers among them (uneasy balance though it may be)?'

In the 1930s, a Russian microbiologist named Georgyi Frantsevitch Gause took a cut at answering Elton's question. Gause's Spitsbergen was a test tube containing competing species of hungry microbes. In a series of experiments set down in his landmark text, The Struggle for Existence, he fed his captive microbes a broth of bacteria and scrutinized their lethal contests.

"Gause's more famous experiments involved two kinds of Paramecium, one superior competitor invariably eating the other's lunch to the loser's ultimate demise. In a less celebrated set of tests, Gause turned his attention 'to an entirely new group of phenomena of the struggle for existence, that of one species being directly devoured by another.' This time Gause pitted predator and prey in the same tube, caging a harmless, bacteria-sucking Paramecium against a relentless protozoan predator called Didinium. An insatiable little monster shaped like a bloated tick, Didinium wielded a poisonous dart for a nose, firing paralyzing toxins into any Paramecium it bumped into. Thus captured, the prey was then devoured whole.

"The first meetings of the two were predictably brutish and short, the sequence proceeding as such: Peace-loving Paramecium, with no place to run nor hide, gets quickly devoured by the predator Didinium. Gorging to its heart's content, Didinium soon finds itself alone and hungry, and perishes.

"Then in steps Gause, playing God, to level the odds. He adds some sediment to the bottom of the test tube -- a refuge, a place for Paramecium to hide. Didinium, however, knows no other strategy. Seeking and destroying every last Paramecium it finds, the savage microbe again eats its way to oblivion. But this time a few lucky Paramecium have remained hidden. With the coast clear, they emerge, and soon the world is crazy again with Paramecium.

"Gause adds one more twist. Every couple of days, he adds a new Didinium to the mix. An immigrant. And with that, the little glass microcosm begins producing beautiful numbers. Logged on a line chart, the populations begin tracing sinuous, oscillating waves, prey leading predator through rise and fall, rise and fall, the eternal waves of a predator-prey equilibrium.

"It was a beautifully naked, if admittedly clinical, demonstration of the finely and tenuously balanced skills of predator and prey, teetering so delicately on environmental fulcrums. But inevitably, it was the prey in charge, Paramecium leading Didinium around by its deadly nose.

"The world according to Gause was a competitive place. And it was governed from the bottom up. The sun shone, the plants grew, animals ate the plants, other animals ate the plant-eaters, one trophic level to the next, all the way to the tip of Elton's pyramid. The world was in a steady-state equilibrium. It all made perfect sense.

"Until a phenomenon called HSS came along.

"In 1960, three eminent scientists from the zoology department of the University of Michigan -- Nelson G. Hairston, Frederick E. Smith, and Lawrence B. Slobodkin -- wrote a soon-to-be-infamous paper called 'Community Structure, Population Control, and Competition,' a five-page theoretical rumination published in the American Naturalist. The paper was cited and debated so heavily that its authors were thereafter known more simply as HSS. Their proposal earned a nickname of its own: The green world hypothesis.

"HSS reasoned that the terrestrial world is green -- meaning that it is largely covered in plants -- because herbivores are kept from eating it all. And what kept those herbivores from turning the green world to dust, suggested HSS, were predators.

"The green world of HSS presented a decidedly different take on how nature worked. The venerable bottom-up perspective had Elton's pyramid progressing smoothly and stepwise from bottom to top, every higher layer inexorably dictated by the lower. HSS, with their hypothetical predators exerting such influence from the top, were fiddling with that sacred pyramid, adding great weight to its peak. In defense of their hypothesis, they cited commonly known plagues of rodents and the outbreaks of insects, apparently following the destruction of their predators. They also raised the legend of the Kaibab.

"The Kaibab legend was the classic and controversial tale of predators having the final word. In the 1920s, on the Kaibab Plateau north of the Grand Canyon, the deer population, by all accounts, exploded. And then, the story goes, as the last edible twig was browsed, the population predictably crashed. There was mass starvation, and there were people there to witness it. There was outrage and blame.

"The standard explanation, one that has since had a long and potholed ride in the ecology textbooks, pinned the deer's irruption on government trappers, who had cleared the plateau of its wolves and mountain lions. The herd's ultimate demise was therefore triggered by a lack of predators.

"HSS used the Kaibab to bolster their case that competition, by itself, fell short of answering ecology's seminal questions on the limits of populations. The phenomenon of predation was now a factor to be heeded. It was a bold hypothesis, abundantly praised and reviled. But what it most fundamentally lacked -- as everyone including Hairston, Smith, and Slobodkin would admit -- was proof."

|

|||

| author: William Stolzenberg | |||

| title: Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators |