| Battleship Potemkin |

|---|

|

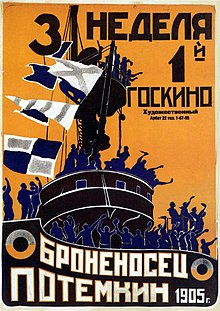

Today's selection -- from Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams by Charles King. At 27, Sergei Eisenstein developed the iconic silent film, Battleship Potemkin:

"Battleship Potemkin became one of his preeminent pieces and certainly one of the most copied works in film history. It was commissioned by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for the twentieth anniversary of the 1905 revolution, but by the time Eisenstein began the project, the end of the anniversary year was only a few months away. He and a vast team worked in Odessa and other parts of the Black Sea region for weeks, using the Hotel London as their base. To save time and money; they scraped together archival footage that could be used in place of new film, (The shots of tsarist ships steaming ominously toward the valiant mutineers are actually old images of the U.S. Navy on maneuvers, the giveaway being a small American flag visible in one scene.) In a mad rush at the end of the year, Eisenstein cut down some fifteen thousand meters of film into a running time of around seventy minutes. 'The fetters of space and the claws of time held our excessive and greedy fantasy in check,' he later wrote, surely with little inkling of the lasting success produced by just over three months of scenario writing, set design, shooting, and editing.

"What Eisenstein injected into the story was its single most memorable -- and in large part imaginary -- element: the slaughter on the Odessa steps. Eisenstein's genius was to place the steps at the center of his film, a scene that he called in his memoirs 'the very core of the film's organic substance and general structure.' Ranks of soldiers and Cossacks fire on the striking workers. When a Cossack strikes a woman across the face with his cavalry saber, we know exactly what has happened in that gruesome and shocking scene, even though the director never shows the sword making contact with her upturned face; the woman simply turns her gouged eye full-on to the camera. In the climactic sequence, a baby carriage teeters on the edge of the staircase then slides horrifically down the granite cataract.

|

| A wide shot of the massacre on the Odessa Steps. |

"In reality, there was no popular memory of a 'massacre on the steps' as the centerpiece of the violence of 1905. The major shooting occurred elsewhere in the city and involved not only the military but also a whole series of self-protection units organized by city neighborhoods to guard against bandits and the inciters of pogroms. The idea for the scene may have come from an illustration of the staircase that Eisenstein found in a contemporary French magazine while doing background research for the film in Moscow. In Eisenstein's retelling, the single bloodiest event of 1905 -- the murder of hundreds of Jews -- faded into the background. Through the film, Odessa was transformed from a place where Jews had been killed in the streets to a city remembered for working-class solidarity and opposition to the tsar's arbitrary rule. It was, to say the least, a heroic act of misremembering.

"When Soviet audiences viewed the silent film, they were witnessing the birth of their own country -- a revolutionary nation that looked back to the heroes and martyrs of 1905. By the time the film was released in 1925, the Soviet Union had succeeded the Russian Empire as the de facto ruler of much of the Black Sea coastline, including Odessa. Yet it was a country without a history. Its ideology proclaimed youth and rejection of the past as the hallmarks of a new social and political order. Even its founder -- Lenin -- lay dead, his legacy uncertain and a host of former courtiers now vying for power. The Potemkin mutiny, in Eisenstein's talented hands, became the Old Testament of the Bolshevik Revolution, a series of events that presaged the triumphant changes of October 1917.

"One of the last places Battleship Potemkin was shown was in Odessa itself. It had played at the Bolshoi Theatre and the First Sovkino Cinema in Moscow in December of 1925 and January of 1926, and when the American film stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford saw it during a visit to the Soviet Union that summer, they hastened its release abroad. Charlie Chaplin pronounced it the best film in the world. It soon played to packed houses in Atlantic City, New Jersey, before arriving in Odessa later in the year. The film had been taken for a dry documentary elsewhere in the Soviet Union and had been screened to half-full houses. But in Odessa it was an instant hit ...

"Battleship Potemkin is arguably the single most important cultural artifact in Odessa's modern history -- a piece of art that did more than any other to encapsulate the city's own image of itself and the way in which it would be remembered for generations to come. If portside hucksters and the mélange of East and West had impressed visitors for much of the nineteenth century, Eisenstein's staging of the Potemkin affair came to define the city in the twentieth. Eisenstein included all the basic elements of the incident that were passed down from the participants themselves, such as the crew's refusal to eat rancid meat as the impetus for the mutiny. But he added the heroic gloss that turned Odessa into the avant-garde of revolutionary change, providing a usable prehistory for the Bolshevik Revolution and, by extension, for the new Soviet state."

|

|

|

author: Charles King |

|

|

title: Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams

|

|

|

publisher: W.W. Norton & Company |

|