Inside Hunter Jim Corbett’s Legendary Showdowns With History’s Scariest Man-Eating Big Cats

British tracker and naturalist Edward James Corbett was commissioned by the Indian government to kill some 30 leopards, panthers, and tigers in the early 20th century.

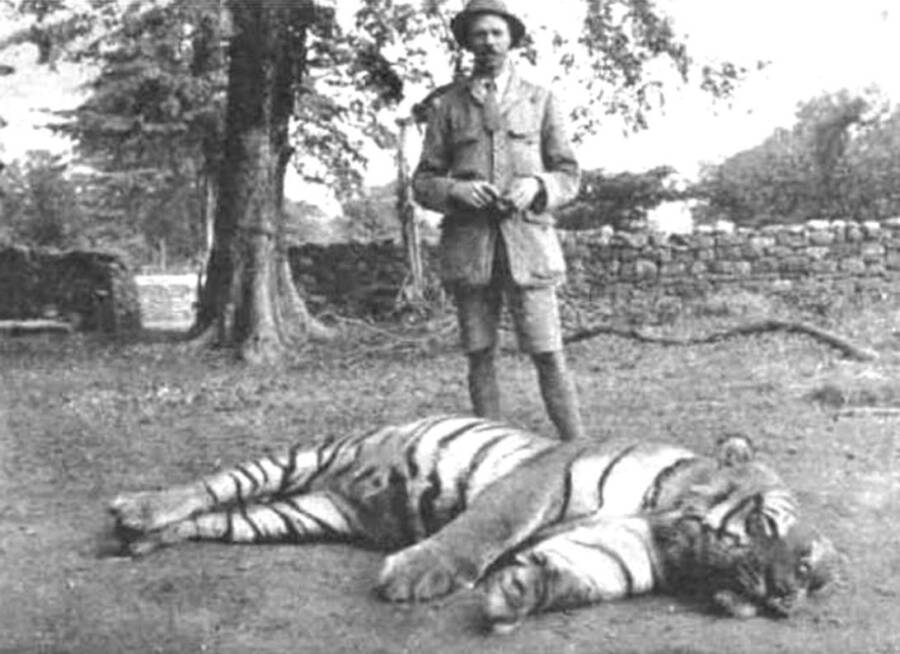

Wikimedia CommonsJim Corbett and the slain “Bachelor of Powalgarh” in 1930.

Jim Corbett was a man of many talents. Born in British India in the late 1800s, his versatility was seemingly a prerequisite for survival. A child of the Kumaon region, its forests inspired his lifelong effort to protect animals and people alike.

Corbett dedicated his later life to preserving India’s dwindling tiger population. As a recreational photographer, naturalist, and author, he would help found India’s first National Park.

Jim Corbett was

bornEdward James Corbett on July 25, 1875, in the Indian town of Nainital, in the wilderness and expanse of the Himalayan foothills. As the eighth of 12 children, Corbett would spend much of his time outside, exploring the region’s natural beauty.

“I have used the word ‘absorbed,’ in preference to ‘learnt,’ for jungle lore is not a science that can be learnt from textbooks,” he wrote in his later life.

His Irish parents, Christopher and Mary Jane Corbett, had moved their family to Nainital in 1862, years before the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh became the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. Corbett’s father worked as the town’s postmaster.

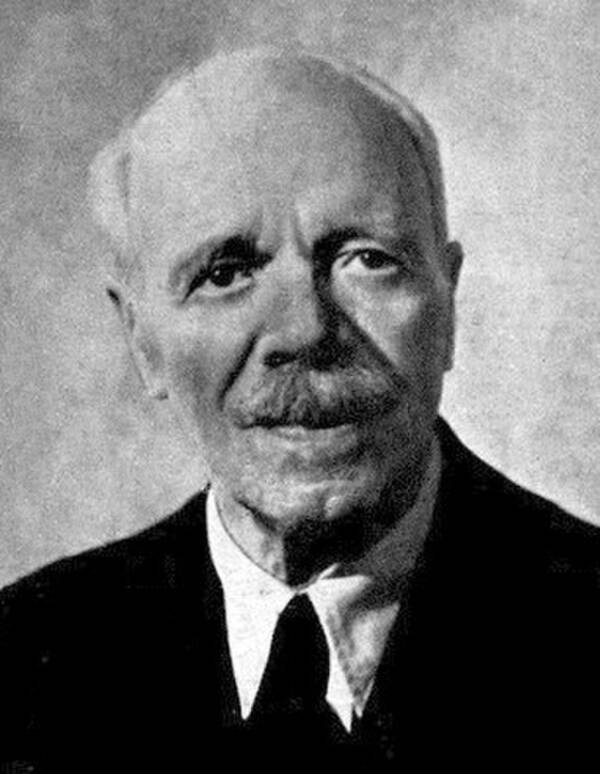

Wikimedia CommonsCorbett killed 33 predators and wrote six books.

Corbett was only 6 when his father died of a heart attack on April 21, 1881. While his mother busied herself tending to European settlers, his brother took over as postmaster. Corbett himself took to the forests of Kaladhungi, where his family wintered in a cottage they named “Arundel.”

As a student of Oak Openings School, Corbett had participated in only a few nature excursions. However, at Arundel, he rapidly grew adept at hunting and tracking. Quitting school at 18, he went to work for the Bengal and North Western Railway as a fuel inspector. Word of his hunting prowess grew, and before long, and the government soon asked him to eradicate the Champawat Tiger.

Jim Corbett Hunts The Man-Eaters Of Kumaon

The Champawat Tiger started killing in Nepal. She had chalked up over 200 victims before being driven into the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. Two hundred and thirty more people would die on her claws and jaws there before Corbett intervened.

After besting the Champawat Tiger, Corbett began documenting the human casualties of the predatory cats he hunted. His books chronicling the 33 predators he eradicated would revolve around the details of the estimated 1,200 people the beasts had killed.

In 1910, Corbett tracked and killed the Panar Leopard, which had reportedly eaten about 400 people. He killed his second man-eating leopard, the Leopard of Rudraprayag, in 1926. The latter had preyed upon pilgrims venturing to the Hindu holy sites of Kedarnath and Badrinath for nearly a decade.

Safari BooksCorbett volunteered in both World Wars and became an honorary colonel.

Examination of the Panar Leopard revealed tooth decay and advanced gum disease. Experts believed this drove it to kill people rather than challenge itself with wild game. Most of Corbett’s kills were cats with similar debilities. Porcupine quills or old bullets created aggravating wounds, driving the beasts from the forests in a man-killing madness.

“The wound that has caused a particular tiger to take to man-eating might be the result of a carelessly fired shot and failure to follow up and recover the wounded animal, or be the result of the tiger having lost his temper while killing a porcupine,” wrote Corbett in Man-Eaters of Kumaon.

Like a pre-war Batman, Corbett would work alone, haunting the jungles with only a faithful dog named Robin at his side. He grew famous for killing village-destroying villains like the Thak man-eater, the Talla-Des, and the Chowgarh tigress without suffering even a scratch.

Wikimedia CommonsA Bengal tiger in Corbett National Park.

Corbett died on April 19, 1955, days after he finished his sixth book, Tree Tops. He suffered a heart attack, as his father had before him. One year later, the state of Uttarakhand renamed the national park he helped found Jim Corbett National Park — one of few instances of a Brit receiving such an honor post-independence.