THE FORGOTTEN HISTORY OF HOW US MARINES AND SAILORS TOOK HAWAII IN AN ILLEGAL COUP

In 1893, US Marines and sailors staged a bloodless coup to seize control of Hawaii. Photo by Luca Bravo on Unsplash; composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

US Marines are known for their amphibious warfare capabilities — projecting power from naval vessels onto beaches or littoral zones anywhere in the world. And while leathernecks are forged on the proud naval traditions and legendary exploits of their forebears, most of America’s “soldiers of the sea” are unaware of the role US Marines played in capturing one Pacific island chain in particular: Hawaii.

The bloodless coup that overthrew the last Hawaiian monarch, Queen Liliʻuokalani, is little-remembered American history. It was the type of action that led legendary Marine officer Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler to say of his career, “I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers.”

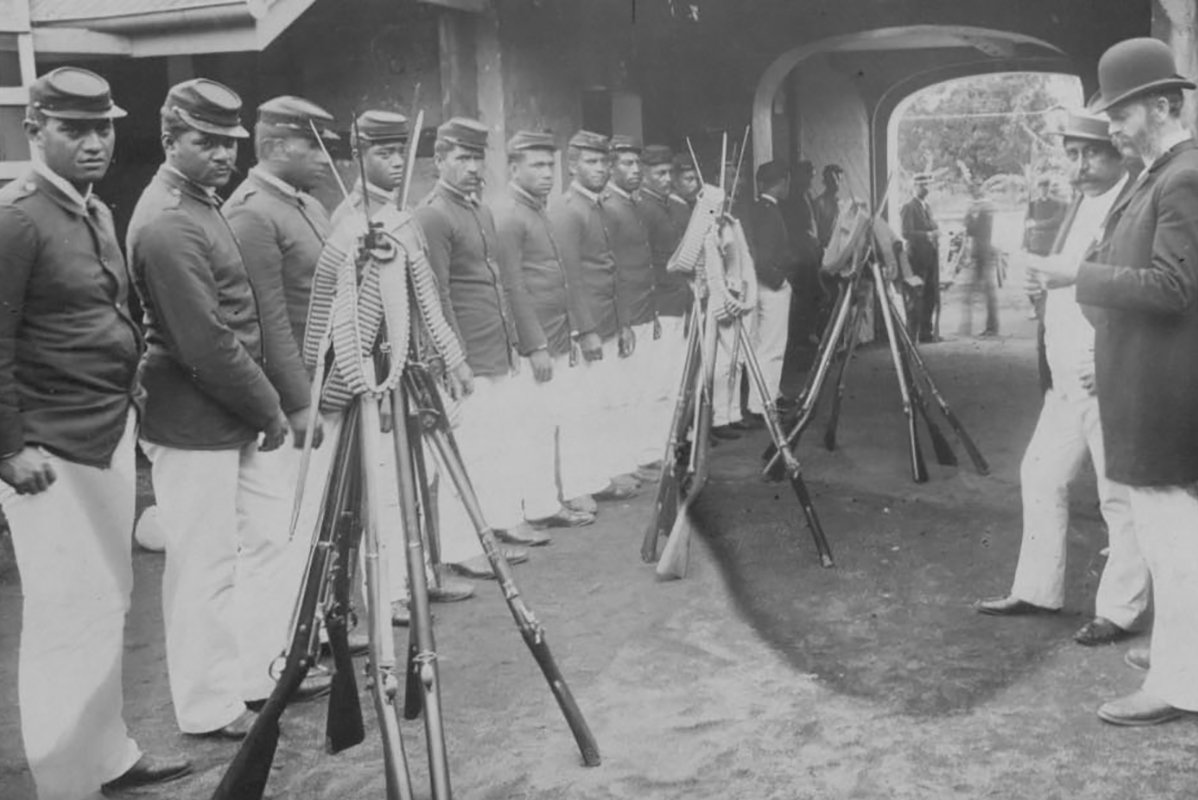

Bluejackets of the USS Boston occupy Arlington Hotel grounds during the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, with US Navy Lt. Lucien Young in command of troops. Site of childhood home of Queen Liliʻuokalani. US Naval History and Heritage Command photo.

Bluejackets of the USS Boston occupy Arlington Hotel grounds during the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, with US Navy Lt. Lucien Young in command of troops. Site of childhood home of Queen Liliʻuokalani. US Naval History and Heritage Command photo.Early in the evening of Jan. 16, 1893, Navy Lt. Lucien Young led a force of 162 American Marines and sailors from the USS Boston as they disembarked the ship anchored in Honolulu Bay and marched up the city’s cobblestone streets roughly half a mile to Aliʻiōlani Hale — then the seat of government for the Kingdom of Hawaii — to carry out a bloodless coup in the name of the US government.

The American force occupied Aliʻiōlani Hale and its adjacent buildings, which stood directly across the street from Iolani Palace, where Liliʻuokalani lived. Although the American force had Gatling guns and light artillery, the queen had a palace guard force of almost 600 soldiers, artillery of her own, and a defensible position.

Rather than put her people at risk, the queen formally abdicated her throne in a conditional letter: “Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

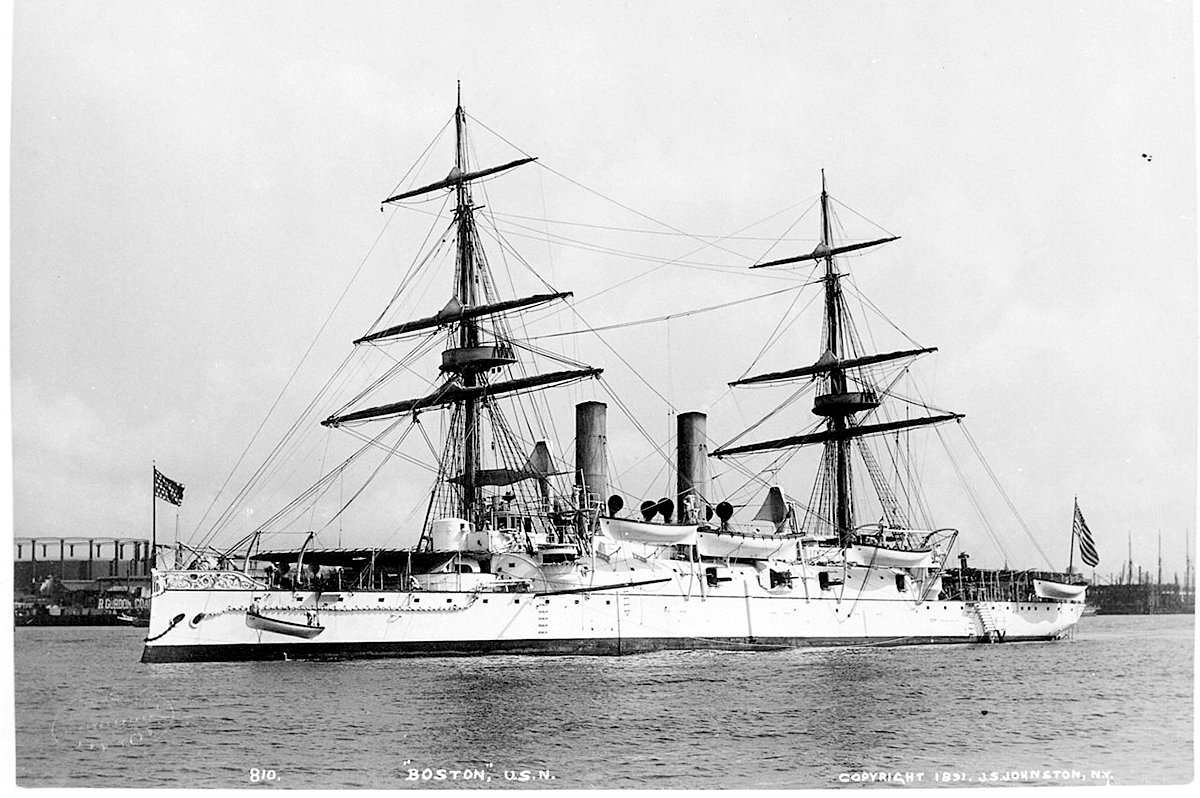

USS Boston in 1891. Wikimedia Commons photo.

USS Boston in 1891. Wikimedia Commons photo.The coup was undoubtedly illegal and not officially sanctioned by President Benjamin Harrison or the US Congress. Its mastermind was John L. Stevens, the US Minister to Hawaii — a US State Department position equivalent in rank to a present-day US ambassador to foreign governments.

Stevens was a journalist, author, minister, and newspaper publisher who founded the Republican Party in Maine and served as a Maine state senator. Like many Americans in the Victorian era, Stevens was a proponent of Manifest Destiny — the belief that the United States should continue its territorial expansion across North America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific.

With the British angling for the strategic harbors in the Pacific archipelago, Stevens believed the US should annex Hawaii, and he wrote to US Secretary of State John W. Foster, “The Hawaiian pear is now fully ripe, and this is the golden hour for the United States to pluck it.”

Stevens’ “golden hour” coincided with Liliʻuokalani’s attempt to ratify a new constitution that would have reasserted the monarchy’s power — largely ceded by her predecessor.

Queen Liliʻuokalani’s household guard being disarmed by Col. John H. Soper, following the overthrow of the monarchy in January 1893. Wikimedia Commons photo.

Queen Liliʻuokalani’s household guard being disarmed by Col. John H. Soper, following the overthrow of the monarchy in January 1893. Wikimedia Commons photo.“The rumor circulated that her new constitution would deny the vote to any haole [nonnative Hawaiian] who was not married to a Hawaiian,” Ruth M. Tabrah wrote in Hawaii: A History. “The certainty of many Americans was that she would sooner see her kingdom placed in the hands of the British than continue a pattern of American influence and American political control. On the morning of January 14, 1893, the queen announced her intention to promulgate a new constitution that would restore actual rule of the kingdom to her as sovereign.”

With their interests threatened by the possibility of the new constitution becoming law, a cabal of businessmen calling themselves the “Committee of Safety“ saw US annexation as the best way to stay in power. The group of powerful plantation owners and financiers was supported by Sanford Dole, a lawyer and descendant of American missionaries in Hawaii. With Stevens’ support, the Committee of Safety conspired to take action.

According to the eventual presidential investigation of the coup in Hawaii: A “small body of men, some of whom were Germans, some Americans, and some native-born subjects of foreign origin” met on the evening of Jan. 14, 1893, and discussed “the subject of dethroning the Queen and proclaiming a new Government with a view of annexation to the United States.”

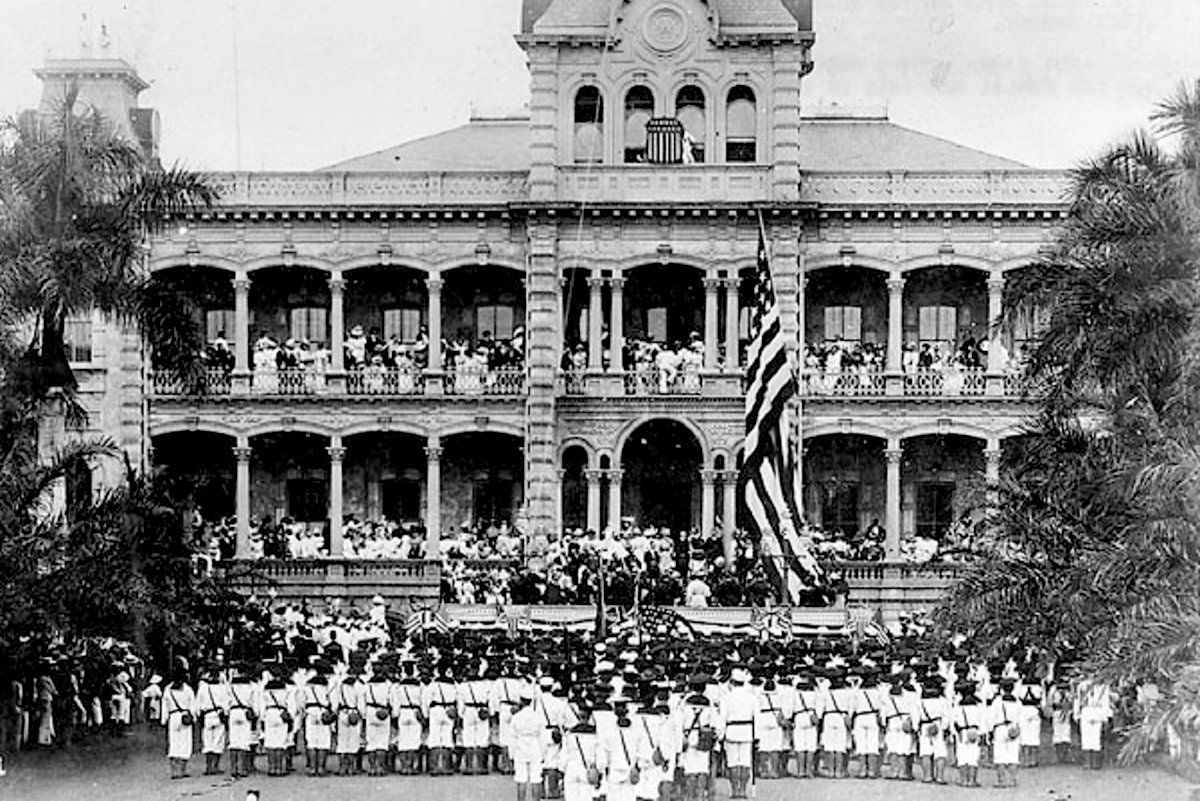

Ceremonies marking the raising of the United States flag at the Old Government Building Aug. 12, 1898. Sanford Dole, who declared himself president of the Republic of Hawaii after deposing the monarchy, is among those present. US Naval History and Heritage Command photo.

Ceremonies marking the raising of the United States flag at the Old Government Building Aug. 12, 1898. Sanford Dole, who declared himself president of the Republic of Hawaii after deposing the monarchy, is among those present. US Naval History and Heritage Command photo.The Committee of Safety asked Stevens for military support under the pretense of protecting American citizens and property in Honolulu. Stevens delivered, ordering Navy Capt. Gilbert C. Wiltse, commander of the USS Boston, to dispatch the ground force.

“In view of the existing critical circumstances in Honolulu, including an inadequate legal force, I request you to land marines and sailors from the ship under your command for the protection of the United States legation and United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property” Stevens instructed Wiltse on Jan. 16, 1893.

Although Stevens was acting on his own without any authorization from the State Department, Congress, or the president, Wiltse carried out the minister’s illegitimate order, and Stevens and the Committee of Safety established a provisional government deemed “The Republic of Hawaii.” Sanford Dole, who was beginning his pineapple business, declared himself president without a popular vote, and the new government found the queen guilty of treason and placed her under house arrest.

US Marines at annexation ceremonies in Hawaii on Aug. 12, 1898. Wikimedia Commons photo.

US Marines at annexation ceremonies in Hawaii on Aug. 12, 1898. Wikimedia Commons photo.The American businessmen lobbied Harrison and Congress to officially annex the Hawaiian Islands, but after Harrison sent an annexation treaty to the Senate for confirmation in his final month in office, newly elected President Grover Cleveland withdrew the treaty. Cleveland appointed James H. Blount to investigate the events surrounding the overthrow of Hawaii’s monarchy, and Blount’s investigation concluded that Stevens acted completely illegally in ordering the operation, which would not have succeeded “but for the landing of the United States forces upon false pretexts respecting the dangers to life and property.”

“The provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States,” Cleveland wrote about the coup. “By an act of war … a substantial wrong has been done.”

Cleveland supported restoring the monarchy in Hawaii, and he received Liliʻuokalani and replaced the American Stars and Stripes in Honolulu with the Hawaiian flag. The US House of Representatives voted to censure Stevens and adopted a resolution opposing annexation. Because American public sentiment at the time didn’t reflect Cleveland’s strong anti-imperialist ideals, Congress did not act to restore the monarchy.

American Marines from the USS Philadelphia raise the American flag at the United States annexation ceremony at Iolani Palace, Honolulu, Hawaii. Wikimedia Commons photo.

American Marines from the USS Philadelphia raise the American flag at the United States annexation ceremony at Iolani Palace, Honolulu, Hawaii. Wikimedia Commons photo.President William McKinley succeeded Cleveland in March 1897, and after running on a Republican Party platform that called for the annexation of Hawaii, McKinley wanted Congress to officially annex the islands. Fearing he lacked the two-thirds majority he needed in the Senate, McKinley called for a joint resolution of Congress — the same way the US acquired Texas. With Congress fearing Japan might make a play for the Hawaiian Islands and the Spanish-American War looming, the joint resolution easily passed.

In July 1898, McKinley signed the joint resolution, officially annexing Hawaii as a US territory. In 1959 — 66 years after the bloodless coup that took the Hawaiian archipelago for the United States — President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation making Hawaii the 50th American state. The US formally apologized to Hawaii in 1993 for annexing the islands, and the apology was codified into law.

When the Marines and sailors from the USS Boston posted up around Iolani Palace in January 1893, the queen’s guards were under orders not to provoke the Americans. So despite a restive night for the Marines slapping mosquitoes, Jan. 17 dawned without violence. The Marines never fired a shot, but their presence and the military power they represented was enough to end a monarchy.

“The way to lose any earthly kingdom is to be inflexible, intolerant and prejudicial,” Liliʻuokalani said later. “Another way is to be too flexible, tolerant of too many wrongs and without judgment at all. It is a razor’s edge.”