https://www.cnn.com/travel/de-havilland-comet-dh106-first-passenger-jet

|

A worker inspects the Christ the Redeemer statue which was damaged during lightning storms in Rio [EPA]

For the old Anglo-Saxon nobility, it was a near genocidal catastrophe. Almost all of the Anglo-Saxon nobles saw their lands and property seized by their conquerors. Within a few short years most of the greatest lords were dead, if they hadn’t already been slaughtered at Hastings.

Some of their lesser kind tried to sustain rebellion and resistance, the most famous of these being Hereward the Wake, who would become a particularly beloved English folk hero subject to revivals of interest in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. But customary brutal efficiency of the Normans proved more obdurate than Saxon resentment as the years rolled on, and eventually all of these rebellions petered out.

Others from the previously ruling Anglo-Saxon nobility fled into foreign exile, as they had done more briefly in the power struggles between themselves or in the years of Canute and his sons, with some even becoming exotic members of the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Empire. There’s a fascinating little known quirk of history that saw a significant exodus of the English flee to the patronage of the Byzantine Empire. Some have asserted that for many generations a kind of New England existed under Byzantine patronage in what is now the Russian controlled Crimea, with four separate chroniclers between the 11th and 14th centuries claiming that between 235-350 ships fled from England to this distant region after the Conquest. All of these chroniclers claim that the refugees founded towns and villages that the Byzantine Emperors allowed them to create and govern, so long as men from these areas served in his military forces and personal bodyguard. Subsequent history and stages of Byzantine collapse swept these English links away, perhaps becoming just a buried DNA trace shared by small numbers of Ukrainians and Russians utterly unaware of their ultimate origin.

Back in England, the Conqueror was coldly determined to break all resistance, and chose overwhelming force of response as the means of doing so. When the remaining northern Anglo-Saxon Earls rebelled, William had ample excuse to remove the last truly significant Anglo-Saxon noble families from positions of influence. His savage response was an orgy of destruction known as the Harrowing of the North, which laid waste to towns, villages and settlements across the entire northern regions of the newly conquered kingdom.

Many historians have argued that the North never fully recovered, and that the modern North-South divide was essentially set by these events almost a thousand years ago. William was so brutal in suppressing revolt that effectively some of the richest regions of his realm became, seemingly permanently, significantly reduced in wealth, population and influence.

What was unique about the Norman Conquest was not the fact that the English had been subdued, or even how close the English came to extinction, but the permanence and the totality of their defeat. Two centuries earlier the English faced eradication and replacement by the Vikings (genetic and cultural forefathers of the Normans, who were merely Gallicised Vikings settled at the mouth of the Seine by treaty between Rollo, first Duke of Normandy, and a French king desperately seeking to buy off persistent raiders). Before Alfred the Great’s miraculous turnaround, it might be accurately said that the English had been reduced to a handful of outlaws in a pestilential marsh. There, perhaps, they had come closer to complete eradication than they did following 1066.

But that was not a permanent reduction, that was not a reduction that would define the difference between the working class and the upper class in England for the next thousand years. The Vikings were a cruel storm, whereas the Normans were a permanent change of climate. It’s estimated that 70% of the private land in England is still owned by families descended from the 20,000 Normans who landed in 1066. While some Normans (and the Bretons who formed part of their number) married Saxon women, it was Norman blood, primarily, that would from that point on flow in the veins of the English upper classes. It’s only amongst the top 1% of our society that Norman DNA had a significant impact, whilst the rest of us (save for some other minor Viking influence) remained solely a mix of Anglo-Saxon and Ancient Briton.

One of the things which is therefore odd about the history of the English and of English genetics is that despite numerous conquests most of us were ethnically very homogenous, with part of our heritage stretching back thousands of years before the Anglo-Saxons arrived, and part of it coming from the Anglo-Saxons exclusively. For almost a thousand years no further conquests came to complicate either our blood or our ways. Immigration was minuscule, statistically irrelevant. Modish modern recasting of our past is that English identity is one of the most mixed on the planet and always has been, a view which exists solely to suppress the uniqueness of England and its people and to deny them any priority in their own land. But it’s a false narrative, shaped solely by modern race hypocrisies and modern ideological impositions.

It’s far more historically accurate to say that the English had the kind of homogeneity you would expect of an island nation with some martial prowess to its name, and certainly far more internal cultural unity than we now possess.

Even the Saxon and Norman division was eventually healed. The Normans were an unusual people, both unusually ruthless in imposing themselves on others, and unusually adaptive to any environment they found themselves in. They tended to quickly conquer, but then relatively quickly assimilate. In France they learned French ways. In England, despite brutally suppressing the people they had conquered, they eventually learned English ways.

It took multiple generations, but there did come a time when no Norman descended lord spoke French as his first language, and when none would think of themselves as Norman rather than English. They came, they conquered…but then they too were conquered, assimilated into the same identity as those they ruled. The Anglo-Saxons won back by time, rather than by arms, what they had lost on the battlefield. While the same people ruled then, those people thought of themselves differently.

They thought of themselves as English. So who, in the end, conquered who?

That provides the English today with a comforting precedent, but it’s not likely to be one that is repeated. Because today the English are at a greater threat of non-existence than they have been since Alfred hid in a marsh. Today, they face an enemy in Islamic arrivals who have all the brutality of the Normans and none of their adaptability. Islamic arrivals have not and will not assimilate to the point of considering themselves English too, or of adapting to and respecting English ways. Instead, Muslims create Muslim only areas where the English are at risk.

What’s worse, the current political and media elite in Britain is completely happy for these arrivals (or others) to entirely replace the English. Imagine if instead of 20,000 Normans there were millions, and imagine if instead of fighting the invasion, every Anglo-Saxon leader had, from the start and with a calculated dishonesty, preferred the invader to their own people.

The fact is that there has been a long and multi-pronged attempt to eradicate the English, conducted quite often by the English themselves, by their educated and indoctrinated elites, by their comfortable and unaffected middle class who still support open borders and hard left parties from a position of being in the least diverse and most safe parts of the country.

Many years ago Orwell noted that the English intellectual despises his own Englishness and despises even more the poorer working class who do not share that learned and affected self-loathing. But what was a sort of sado-masochistic belief of those most removed from reality has become the operating belief of the society as a whole. It used to be thought that rough Anglo-Saxon pragmatism, a certain realism that disdained abstract approaches contrary to perceivable reality, was a feature that protected the English nation from the excesses that wracked their Continental neighbours.

The English were too sensible to fall to communist revolution. The English were too in touch with reality to go for extreme hard left social positions. For centuries English compromise was not moral compromise, but a sane man’s avoidance of insanity. It gave English governance a stability found nowhere else in Europe, and even when fanaticism did lead to civil war, what is remarkable about the English is that both sides were chastened by it, and learned to compromise better. that’s what the Restoration showed, and it’s what the bloodless Glorious Revolution showed too.

Eventually Saxon common sense had so blunted Norman cold ambition that the English were better at resolving the differences between themselves than other places were, especially the differences between the social classes.

All this survived so long as they were essentially one people….and so long as the intellectuals were not directing the social attitudes of the nation. The strongest defence of English sanity and its often unwritten constitutional settlement, was that not many of us went to university.

Now though, the attitude that Orwell wrote about is totally dominant, and it welcomes invasion and the subjugation of the English with open arms, indeed with active and malign assistance from its police, its judiciary and its media and political class.

For long years the English were quietly but consistently being replaced, abused and betrayed, the demographics of their nation fundamentally altered against their will, whilst at the same time their very existence, their own ethnicity, was denied. They have been told for 70 years that they do not in fact exist, that they are invaders themselves as if a millennia and a half of ownership counts for nothing and as if their blood ties to an even older Briton heritage don’t exist either. Looking at the difference between 19th century and 20th century talk on these topics is remarkable.

English school texts used to talk about the history of the English race, knowing full well there was such a distinct thing and that it was distinct and valuable not just ethnically, but in terms of its culture and achievements too. Today, the race is dropped except when calling them racist. Today, it has become ‘you do not exist…and your existence is the greatest evil there ever was’.

Go into any of those outmoded things called a bookshop and you can find whole walls of texts devoted to this message. Do a Google or an Amazon search on the English or on the British Empire. Post-colonial grievance porn will predominate what you find. For every mild defence of English history and heritage, the kind of still too polite and still too diffident rebuttal offered by a Douglas Murray or a Niall Ferguson, there will be a hundred books spreading the poison of what is essentially Anglophobia (a far, far more real thing, with far, far less justification, than ‘Islamophobia’).

We live in a nation that teaches hatred of our own officially, while pretending that hatred of the Other is the really big problem.

Third generation immigrants comfortably settled in England (and doing very well socially and financially, thank you very much) will tell you how utterly vile all English history was, how the English invented racism and conquest, how the British Empire was worse than Nazi Germany, how Churchill was in favour of gas chambers or Britain invented concentration camps or how India was ruined by the Raj or how Churchill (again) deliberately starved millions in Bengal.

All of these are lies, of course. But they are the common intellectual understanding of the people who rule the English now, and the half-arsed, hypocritically racist truisms with which anyone who gets to an upper level of media and politics has been schooled. They are the ‘I know a tiny fraction of history, but I don’t know enough to know the truth’ version of history that you will encounter in online debates and from both students and professors at English universities.

I don’t think people realise just how fully bizarre it is to have the common assumptions of a people become both that they don’t exist and that their existence explains all evil, at the same time, and for everyone to go around acting as if this is normal. The only other people in the world who have been subjected to this level of hate and gaslighting regarding their identity are the Jews, who have of course suffered this for longer and who also have very many of their own doing it (again, indoctrinated leftists).

Under Conservative governments, we have had people embarrassed to fight back or oppose any of this, or people who support insane levels of demographic replacement for purely selfish economic reasons. Official conservatism has from the 1960s on (and really sooner than that) been terrified of the social stigma of Englishness and of celebrating Englishness. Like others in their social class, alleged conservatives of the Official Blue Party learned at university and at dinner parties that actually liking the English was vulgar and unsophisticated, and that sneering at them was much more nuanced and acceptable.

Attitudes to Englishness divide primarily on class grounds, with the people with the least money and power considering it natural and good to favour your own, and the people with the most money and power considering it natural and good to prioritise and favour anyone else except your own. Once you had that intellectual disdain for the English (based on revisionist and malign history often penned by outright Marxists) percolate through the whole of ‘polite society’ and become the normal lesson of the education system, you ensured that you would eventually get a government that really does want to see the English wiped out.

Not just culturally. But actually extinguished. As a history, as a people, as anything at all except an evil that has been rightly removed from the world.

That is the government and the ruling class that the English have today, even though its membership is primarily white still and many of its chief commissars and apparatchiks are genetically English themselves.

According to now official mantra and even sentencing for crime, the only English that are decent and tolerable are the English who accept, welcome and speed their total demographic replacement and extinction. You can have a place at the top table for one or two more generations if you work assiduously to ensure that your people no longer exist in any meaningful way. If you hate them and despise them, if you base your own idea of self-worth in denying their worth, then you can become a Prime Minister or a Home Secretary or a sitting Judge. But ONLY if you pretend that it does not matter that a million little white children were raped, and that talking about that is far worse than doing it. ONLY if you pretend that footage of huge armed Muslim gangs terrorising white people isn’t real, whilst you imprison people for sharing it.

My American friends and Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders too experience something similar, but I think as adjuncts and versions of this Anglophobia in power. When the US is demonised and hated it is specifically the white portion of America that is demonised and hated, and even more specifically the Anglo heritage of this successor nation. The same is true in Canada, or in Australia, and especially true in New Zealand (as an interesting aside on these attitudes, the Māori people designated as especially worthy by being indigenous have been in New Zealand a shorter length of time than the English have been in England. But the English are never recognised as indigenous, nor is any other white population anywhere in the world).

Kamala Harris recently praised Joe Biden as one of the most consequential Presidents in US history. In one sense, if you take consequential as a positive, it is an absurdity. But in another way it’s probably the most honest thing she has ever said. The half-dead zombie that is Biden is not consequential in any positive fashion or as an individual imposing himself on history. But he is extremely consequential in terms of the impact of his administration, from the nature of its illegitimate arrival to the nature of his personal ignominious departure. He is toweringly consequential if you take that to mean negative consequences inflicted by his administration in his alleged period of rule.

Keir Starmer in the UK is already similarly consequential, after only a month in power. What Blair began, he will finish, just as what Obama began, Biden continued. And that’s a war on the English, a racial war on the English and anything they ever built or their descendants ever built (even their rebellious descendants).

Not since 1066 has a government in my land so hated and despised the people it rules, and been so determined to enslave, reduce, deny, exploit and destroy them. What is happening with mass immigration, with unacknowledged but real Muslim conquest, and with erasure from both the history books and the streets, represents a deliberate attempt to expunge a distinct people from the world, to consign them solely to history. And if you don’t believe that is true, visit the parts of Birmingham or London or Bradford where it has already happened, and find me an Englishman there.

Jupplandia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You're currently a free subscriber to Jupplandia. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

By Ryan McMaken

August 15, 2024

“Democracy” is one of those terms that is essentially useless unless the one using the word first defines his terms. After all, the term “democratic” can mean anything from small-scale direct democracy to the mega-elections we see in today’s huge constitutional states. Among the modern social-democratic Left, the term often just means “something I like.”

The meaning of the term can also vary significantly from time to time and from place to place. During the Jacksonian period, the Democratic party—which at the time was the decentralist, free-market, Jeffersonian party—was called “the Democracy.” By the mid twentieth century, the term meant something else entirely. In Europe, the term came to take on a variety of different meanings from place to place. The Mises ReaderMises, Ludwig vonBuy New $12.95(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

The Mises ReaderMises, Ludwig vonBuy New $12.95(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

For our purposes here, I want to focus on how one particular European—Ludwig von Mises—used the term.

Although many modern students of Mises are often highly skeptical of democracy of various types, it is clear that Mises himself used the term with approval. But, Mises used the word in a way that was quite different from how most use it today. The Misesian view contrasts with modern conceptions of a “democracy” in which majority rule is forcibly imposed upon the whole population. Because modern democratic states exercise monopolistic power over their populations, there is then no escape from this “will of the majority.”

Misesian democracy is something else altogether.

Mises’s vision of democracy must be understood in light of his support for unlimited secession as a tool against majoritarian rule. For Mises, “democracy” means the free exercise of a right of exit, by which the alleged “will of the majority” is rendered unenforceable against those who seek to leave.

Moreover, we can only understand Mises’s idea of democracy if we note that Mises’s conception of a liberal “state” is not really a state at all; it contradicts the common definition of a state as an organization with a monopoly on the means of coercion. For Mises, membership within a “free” state is ultimately voluntary since secession remains always an option.

Mises’s View of Self-Determination and Secession

Mises supported the idea of a polity he called a “free national state.” However, Mises’s national state is not a monopolistic state because Mises maintained that “[n]o people and no part of a people shall be held against its will in a political association that it does not want.”

For Mises, the people of any portion of a national state are free to exercise their right of self-determination and by exiting the state via secession. As Mises put it:

The right of self-determination in regard to the question of membership in a state thus means: whenever the inhabitants of a particular territory, whether it be a single village, a whole district, or a series of adjacent districts, make it known, by a freely conducted plebiscite, that they no longer wish to remain united to the state to which they belong at the time, their wishes are to be respected and complied with. …If it were in any way possible to grant this right of self-determination to every individual person, it would have to be done.

Mises contrasts this type of free association with the “princely state” which is essentially the modern state as we have come to know it. The princely state, Mises writes, “strives restlessly for expansion of its territory and for increase in the number of its subjects. …The more land and the more subjects, the more revenues and the more soldiers.” When this type of state is not expanding, it is busy maintaining its borders, and thus, once within the borders of this state, all populations are denied any right of self-determination. After all, to tolerate self-determination—and the right of secession that naturally follows—would be to tolerate the dismemberment of the state.

Mises presents an alternative:

Liberalism knows no conquests, no annexations … the problem of the size of the state is unimportant to it. It forces no one against his will into the structure of the state. Whoever wants to emigrate is not held back. When a part of the people of a state wants to drop out of the union, liberalism does not hinder it from doing so. Colonies that want to become independent need only do so.

Only if we consider the context presented by Mises here can we understand Mises when he presents his definition of democracy: “Democracy is self-determination, self-government, self-rule.” Put another way, “democracy” means groups of people—including even very small groups of people—can freely chose either to remain within a certain state, or to leave. Thus, we see that this idea of democracy is incompatible with the very idea of the modern state.

For Mises, democracy definitely does not mean what it has come to mean in modern usage: that all citizens within a specific state territory are bound to submit themselves to the laws approved by that territory’s ruling majority coalition, no matter what.

The Problem of Majority Rule

Indeed, Mises was thoroughly acquainted with the problem of majoritarian rule and how it is used to strip individuals of their rights. This process is especially dangerous in diverse societies where the overall population contains many cultural groups with incompatible values.

Mises writes that in culturally diverse territories, Omnipotent Government:...Ludwig von MisesBest Price: $16.61Buy New $1.99(as of 07:25 UTC - Details)

Omnipotent Government:...Ludwig von MisesBest Price: $16.61Buy New $1.99(as of 07:25 UTC - Details)

the application of the majority principle leads not to the freedom of all but to the rule of the majority over the minority. … Majority rule signifies something quite different here than in nationally uniform territories; here, for a part of the people, it is not popular rule but foreign rule.

Mises notes that for those on the losing side—that is, those within the out-of-power minority cultural group—majority rule essentially means a permanent loss of any ability to meaningfully affect the policies adopted by the state. Those groups that have little hope of competing with the majority coalition have essentially been conquered and are subject to a type of “foreign rule.”

Mises understood that the only sustainable solution to this problem is to respect the right of self-determination secured by secession.

Without this right of self-determination and unlimited secession every state is, in practice, a monopolistic state that can impose its own values and agenda on the entire population. The presence of elections and “democratic” institutions—democratic in the common, modern sense—does little or nothing to mitigate the state’s power over those who would prefer to leave or govern themselves differently.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org are not necessarily those of the Mises Institute.Today's selection -- from The Fixers by E.J. Flemming. Howard Strickling, Head of MGM Publicity, "fixed" star's problems during Hollywood's golden age.

“In late 1940, Strickling was called in to keep dozens of stars out of the press or jail. One big problem was Lionel Atwill's parties. He was born in England and came to the U.S. in 1932, building a career portraying suave villains in horror films such as Dr. X (1932), Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), and Son of Frankenstein (1939). During his loan-outs to MGM, Atwill became friendly with many actors and executives. He lived in a lovely Spanish hacienda in Pacific Palisades at 13515 d'Este Drive and cultivated an image as an erudite country gentleman surrounded by English master paintings and antiques. But his dark side was obsessed with murder trials and his weekly sex parties. The parties were by invitation only, and guests had to bring a doctor's letter certifying a clean bill of health. After a formal dinner, guests retired to the living room and ceremoniously removed everything but jewelry. Atwill assigned partners according to personal preferences and visited different rooms during the weekend-long party.

“Strickling knew dozens of MGM stars visited the parties, including Gable, Crawford, Stanwyck, Dietrich, and allegedly Mannix. Atwill's soirees remained a Hollywood secret until early 1941. His 1940 Christmas party included several underage girls, and one 16-year-old Minnesota runaway named Sylvia claimed she became pregnant there. Atwill was found innocent at trial but subsequent court proceedings led to a conviction for perjury. Strickling prevailed upon the police and the prosecutors not to investigate his parties any further, and Sylvia was sent home from L.A. with a cash settlement.

“In February of 1941, as the Atwill party stories filled front pages, a Hollywood legend was dying in a small bungalow in Beachwood Canyon. For 25 years, Larry Edmunds' cramped Hollywood Boulevard bookstore was a favorite of the movie elite like W.C. Fields, the Barrymores, Basil Rathbone, and every beautiful actress in Hollywood. Edmunds had a voracious sexual appetite and affairs that included Mary Astor, Marlene Dietrich, Paulette Goddard, and dozens of others. He also slept with men. But by February 1941 he had drifted into alcoholism and mental illness and was living in a garage apartment at 2470 Beachwood Drive, consumed with alcoholic delusions. Police found his head wedged into the stove, dead from gas fumes, near a suicide note describing little men he saw crawling through the walls trying to kill him. Of more concern to Strickling, after he received the call from police, was the house full of mementoes from MGM stars, both male and female. His men rushed to the house to remove hundreds of notes and gifts from lovers of both sexes.

|

| Hollywood movie studios in 1922 |

“In the early months of 1941, MGM began filming Dr. Jekyll and Mr.Hyde, with Spencer Tracy as the crazed doctor. He threatened to walk out unless Ingrid Bergman was given the sexy role of Ivy, the doctor's love interest, rather than Victor Fleming's choice, Lana Turner. The studio bowed and Bergman got the part. She was married to a Swedish doctor and had an infant daughter, but once filming began she slept with Fleming and Tracy, who stole the 26-year-old from his old friend. The fight over Bergman led to frequent arguments between the normally close friends. The fling lasted for several months until her husband heard about it and approached Mayer. Mannix ordered Tracy to end the affair or be fired, while Strickling told writers that Tracy was just ‘mentoring; the young actress and arranged photos of the two at a Beverly Hills ice cream shop sharing milk shakes.

“Tracy's next fling would last 30 years. When Katharine Hepburn first came to Hollywood, one of her RKO bosses described her as ‘a cross between a monkey and a horse.’ She wasn't the typical Hollywood ingenue: she was covered with freckles. David O. Selznick found her ‘sexually repellent,’ and described her as a ‘boa constrictor on a fast.’ Writer Dorothy Parker described her acting talent as ‘running a gamut of emotions from A to B.’ But fans loved her. Born into a wealthy Connecticut family, she moved to Hollywood in 1932. She left her husband behind, refusing to let him come along. But she did bring best friend Laura Harding, an heiress to the American Express fortune. The two were inseparable. Even Hepburn's marriage, forced upon her by her family, didn't end the strange relationship. She and Harding lived in a Coldwater Canyon house that had once belonged to Boris Karloff. By the time she met Tracy in early 1941, she was an established star with a resume that included A Bill of Divorcement (1932), Bringing Up Baby (1938), and The Philadelphia Story (1940).

“She had relationships with men and women. Her men included Leland Hayward and Charles Boyer (both were married), and she lived with Howard Hughes. She called them her beaus but continued to share the house with Harding. The couple's weird arrangement was often discussed, since they acted as a couple and Harding described herself at RKO as ‘Kate's husband.’ Hepburn described her actual husband as being ‘swell about everything,’ and he stayed in Connecticut until she divorced him in 1936. Harding accompanied her to Mexico for the quickie divorce. In early 1941 Tracy and Hepburn were cast in Woman of the Year. The sexual tension between the two was evident from the first day. It's hard to explain why they got together. Tracy was an absentee married man and Hepburn had an aversion to marriage, whether from her earlier failure, her sexual preferences or, as she told writers, because ‘actors should never marry.; For Tracy's part, perhaps at 41 (to her 34) he wanted to trade affairs for a more permanent—but still illicit—relationship. Hepburn knew that Tracy was an alcoholic; mothering the recalcitrant drunk fulfilled some need for her. Whatever the reason, by the time shooting ceased in October 1941, the two were a couple.

“Strickling had an odd challenge with the Tracy-Hepburn pairing. For the most part, Tracy's indiscretions went unpunished in the press. He was so unfaithful that he appeared faithful. Louise lived in their Encino ranch and Tracy lived in hotels, but they spoke daily, and on most weekends he visited his children. Louise founded the John Tracy Clinic, named for their son (who was born deaf), using a sizeable portion of her own wealth. She raised millions to found research and treatment centers for deaf children. She also served on a variety of charity boards and was a sympathetic figure and a press favorite. Somehow his relationship with Hepburn went uncommented-on.

“At the same time in early October 1941, Strickling received a frantic phone call from Robert Taylor. His arranged marriage to Barbara Stanwyck was bizarre. It wasn't sexual other than experimentally, and he sometimes tested the waters with other women if the mood suited him. Stanwyck bullied Taylor in front of his friends. She once strode into their family room while Taylor had a drink with John Wayne and said, ‘Send your friends home. It's time for bed.’ He meekly complied, shrugging his shoulders.

“During that summer, 1941, Taylor had filmed Johnny Eager with Lana Turner. She made plays for most of her leading men and, Taylor's sexual identity and marital status aside, she went after him. In her memoirs Turner suggested she walked away from the affair because she didn't want to ‘break up a marriage.’ More likely, she walked away when Taylor told Stanwyck of his interest in the younger star. Even though his was a marriage of convenience between friends arranged by their studio, Stanwyck reacted strangely. She tried to kill herself.

“On October 7, 1941, Taylor found her in the bathroom bleeding profusely from gashes in her arms. She had severed arteries in her wrist and forearms and would have bled to death had Taylor not stumbled upon her. Strickling had her quietly taken to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, the favorite for the MGM doctors. The press was told that Stanwyck was trying to open a jammed window and had accidentally cut herself. In an odd coincidence, Strickling would use the same excuse after a 1952 suicide attempt by Lana Turner.”

|

|||

| author: E.J. Flemming |

| |||||||||||

|

|

Today's encore selection -- from Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism by Bartow J. Elmore. Sugar and the 5¢ Coke: "It is no small wonder, then, that Coke's first customers loved, even craved, a daily dose of Coca-Cola. After all, Pemberton's original formula called for over 5 pounds of sugar per gallon of syrup. At the turn of the twentieth century, each 6-ounce Coca-Cola serving contained more than four teaspoons of sugar, a concentration that would likely have overloaded consumers' taste buds were it not for the high concentration of acids that helped to balance Coke's flavor profile. (Today, phosphoric acid makes Coca-Cola syrup's pH so low that trucks transporting the concentrated mixture require hazardous material placards to be in compliance with federal transportation laws.) Pemberton had come up with the perfect sugar delivery system, one that made people feel good without overwhelming the tongue. As a result, by the mid-1910s, Coke was the single largest industrial consumer of sugar in the world, funneling roughly 100 million pounds annually into customers' bodies. All that sugar cost Coke money, and since its founding, the company had scoured the world, seeking out suppliers that could offer the lowest prices for its most important ingredient.

"Without cheap sugar, Coke had no business. The company made its millions selling an inexpensive, nonessential beverage in volume, and it could only turn a profit on bulk sales if it kept raw material costs down, especially for sugar, its most expensive ingredient by far. Customers simply were not willing to pay a premium price for soft drinks. Remarkably, from 1886 to 1950, Coca-Cola maintained a 5-cent price for its beverage. This was due in part to Coke chairman Robert Woodruff's constant vigilance. He insisted that company bottlers and soda jerks maintain this price for Coke, even when operating expenses increased, and he spent millions on advertisements featuring Coke's nickel price in an attempt to ensure local bottler and retailer compliance with his policy. In the 1930s, when Coke began a concerted campaign to sell its beverages in coin-operated vending machines that only accepted 5-cent coins, Woodruff had an added incentive to preserve the nickel policy. Technology dictated that any price increase in Coke would require a jump to 10 cents in order to meet single-coin vending machine requirements, a change, executive Ralph Hayes noted, that would have been 'murderous' to the company."

|

The Churches Have Betrayed Christianity

The globalist progressive capture of Christian churches is a key component of this battle.

We have become very used to political betrayal. How many times have allegedly ‘conservative’ politicians and parties betrayed us? How many times have we got used to these people wrapping themselves in the flag when they needed our vote, but governing as Globalists and woke liberal progressives?

More times than can be counted.

Jupplandia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

These people said they believed in low taxes, then raised them. These people said they believed in their country, then attack its history or attack people who want to make it great again. These people said they would oppose crazy spending packages and reduce debt, then support the crazy spending and raise the debt.

These people lunch with their supposed political rivals, and sneer at their own political base.

We have become very familiar with the polite Establishment Republicans, and the Uniparty Republicans, and elsewhere the alleged conservatives in the UK, Australia, New Zealand or Canada who go along with every Globalist policy and every woke agenda just as enthusiastically as their leftist opponents.

But there are other sources of belief and there are other institutions with influence over the direction of our society, aren’t there? There are the Christian churches, each with a hierarchy of ministers and administrators and Bishops and the like, each with considerable resources to apply. What about them?

Mainstream political conservatism has been betraying us for decades. But how much worse is it when that same betrayal comes from what should be our spiritual leaders, the people who more than any others should gird us for the defense of our values, and inspire us to fight to defend our Christian heritage?

These churches and their clergy, surely, should have been the firmest defenses of our heritage, our identity, our Christian morals and values. The Western world, the core of the western world, was once, after all, known as Christendom.

In previous centuries, when Islamic hordes tried to seize and control the West, Christians of strong belief met them, defied them, and defeated them. France (the Kingdom of the Franks) was saved from Ummayyad Islamic conquest by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732 AD. From the Battle of Covadonga (718 or 722) to the final culmination of the Reconquista and the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Grenada in 1492 to the Christian forces of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the Iberian Christians battled for centuries to save themselves from Islamic rule. At the naval Battle of Lepanto on the 7th October 1571 the Holy League of Catholic states defeated the Ottoman Empire and ensured that western Europe would remain Christian. Earlier than that, the first great Siege of Vienna saw the 100,000 strong army of Suleiman the Magnificent halted by an opposing Christian force only one fifth as large. In 1683 the Ottomans again besieged Vienna, this time for two months, and again were turned back, this time by a Christian Coalition of the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth under the joint command of King of Poland, John III Sobieski.

All these Christian armies were armored in the faith, inspired by Popes, and firm in their understanding that Christianity must defend itself. In those centuries, Christian priests would exhort battle against the enemies of Christ, or join the battle themselves, and would not treat the milder passages of the New Testament or the restrained personal example of Christ as an instruction that they should welcome their conquest by another faith or meekly submit to their own destruction. For century after century, Christianity was confident in its right to defend itself and its duty to preserve Christian lands as Christian, to hand these beliefs AND these portions of the Earth together to the next generation.

They even sought to reclaim that which had been lost, as the Crusaders did….a task that did not initiate conquest, but responded to six centuries of Islamic conquest. The crusader cry of Deus Vult (God Wills It!) first chanted as a rallying cry during the First Crusade in 1096, actually came directly from Pope Urban II in a speech to the Council of Clermont in 1095. Robert the Monk’s eyewitness account says that the Pope’s speech was so powerful and moving that the cry went up independently from several voices, all struck at the same time with these words, and that Pope Urban II replied:

“Unless the Lord God had been present in your spirits, all of you would not have uttered the same cry….Let this then be your war-cry in combats, because this word is given to you by God.”

Today, it would be easier to find a Christian priest who sneered at Deus Vult as a Christian version of Allahu Akbar than it would be to find one prepared to describe it as a phrase given to Christians by God. But look at the difference in context and meaning. The Islamic ‘God is great’ has been delivered by those who have always spread their faith by the sword, whereas the Christian ‘God wills it’ was first invoked by those who had already been attacked for centuries. Deus Vult is about picking up the sword to defend Christians after harm has already been inflicted on them. The priests and Pontiffs of the past understood that difference.

They understood that while there is shame and sin in putting innocents to the sword, there is no shame or sin in using martial skill to defend them, their faith and their land from others. Of course Christians have committed atrocities, and individual Christians have been brutal conquerors or venal priests. But there is still a vast gulf between a faith spread first by threat, and a faith spread first by persuasion, just as there is a difference between striking down anyone who stands in your way or for your sadistic pleasure, and resisting violence with violence in defense of your own.

If our priests had been what they are now when earlier Islamic armies threatened the West, the Christian era would have come to an end an awful lot sooner. In the modern world we face an Islamic conquest of the West that the Christian churches actively support. Whilst their own congregations shrink and die, they offer churches up for Islamic and pagan ceremonies, or they instruct their dwindling almost vanished flocks to treat vast numbers of fighting age men prepared to literally invade the West by boat and dinghy as being little lost sheep and lambs of no possible threat to anyone. Many of the NGOs helping the mass immigration invasion of the West are faith based organisations backed by the churches. Many of the remaining priests still at the pulpit are obsessed with the alleged sanctity and angelic splendor of migrants, while utterly unconcerned about the safety and lives of their actual neighbors.

A church in the UK some time ago gave a typical example of this. It was a minor incident but a symbolic one. Old and beautiful stained glass windows showing traditional Biblical scenes were removed and discarded. In their place went a modern stained glass window created by a woke artist to celebrate migrants. Dinghy invaders, most of whom are fighting age unaccompanied men from dangerous places with different (and often disgusting) cultural values, were depicted as flawless, blameless, perfect people (with an unrealistic number of women and children) just dreaming of safety.

The churches no longer have anything to say that speaks to their people, because they aren’t in the least bit concerned with the people from whom their congregations once came. They are in love with the exotic and the alien, and at war with the familiar and the citizen. Their feet are set upon narcissistic paths of woke virtue signalling, rather than on the path of real virtue and real values.

Nor do they seem to have any significant interest in Christianity. What they seem to do for a living is try to find Christian texts and instructions which, once vigorously deprived of all context and cherry-picked and deliberately misinterpreted, can be used to validate the beliefs and causes they do care about, which are woke ones.

Listening to the modern woke priest or alleged Christian is no different to listening to a Just Stop Oil campaigner or a rabid Donald Trump hater or a George Soros purchased District Attorney. These people are not the clergy of Christ, they are another branch of the clerisy of Wokeness. They are radical left social workers and activists, all the way up to figures like the Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury and the (anti) Catholic Pope Francis. The current Pope in particular is a checklist of Globalist and leftist progressive cliches who seems barely aware that the organisation he heads is not the Eu, the UN or the WEF but a church representing 1.2 billion people, many of whom are not woke.

Even sympathetic fellow Globalist progressives struggle to present the current Pope as anything other than their guy in the Vatican. Here’s Wikepedia on the things that Pope Francis really care about:

“He maintains that the Catholic Church should be more sympathetic towards members of the LGBT community…Francis is a critic of unbridled capitalism, consumerism, and overdevelopment, he has made action on climate change a leading focus of his Papacy,,,in international diplomacy, Francis has criticized the rise of white-wing populism….helped to restore full diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba, negotiated a deal with China to define how much influence the Communist Party has in appointing Chinese bishops, and has supported the cause of refugees…calling on the Western World to significantly increase immigration levels.”

So, a Pope who does deals with Communism, which has persecuted Catholics and Christians in China for a century and still does, and who shares Marxist attitudes to capitalism. A Pope obsessed not with Christian imagery and the Kingdom of Heaven, but with the secular apocalyptic belief system of Climate Change. A Pope who shares the hilarious (but also deeply hypocritical and authoritarian) progressive obsession with an imaginary ‘far-right threat’ and such Globalist dog whistle fictions as ‘dangerous Christian Nationalism’. A Pope who sees millions of traditional Catholics and ordinary white people as a threat. A Pope with an Antifa student understanding of economics, opposed to the very thing that has made the West successful. An Open Borders Pope who sounds like the writer of a Guardian newspaper opinion column.

The list goes on to praise Pope Francis for apologizing for the Church’s role in the “cultural genocide” of indigenous Canadians, an apology based on a complete fiction representing a kind of blood libel against white Canadians of European descent (the ‘native genocide’ scandal was based on allegations of mass graves which have never been found and confirmed but which did result in attacks on Catholics and racism towards white people).

Pope Francis does indeed represent many Christians. Unfortunately he represents the ones who enter a Christian church mainly to destroy it from within or turn it into a semi-Marxist outfit ranting against capitalism and white people. He is the long march through the institutions when that march reaches the final peak in church hierarchies. And his views are exactly the same as the views of any member of the new global elite.

There’s nothing specifically Catholic about him. He might as well be Netflix, or Barack Obama.

And this is fairly typical of ALL the Christian churches and their leaders. Justin Welby, the head of the Anglican Church, might as well be a Labour politician. Most of his thoughts and sermons seem geared towards the exact same things as those given by Pope Francis. Support for open borders, support for migrants and refugees, support for the idea of Christianity not as a serious faith with a 2,000 year old history but as a shoddy modern grab bag of the most asinine ideas available today, a portmanteau of progressive cliches and hypocrisies. Welby has driven traditional minded portions of the Anglican communion away, inspiring a large portion of what was the global Anglican church to break out in open rebellion. Meanwhile, the churches in the UK are empty and the mosques are full.

Or how about the Baptists, who are somewhat bigger in the US than they are in the UK, but likewise seem to mainly consist of representatives who only think of Christianity as a sort of code for wokeness, a traditional language you can translate wokeness into to support woke conclusions. The Baptists have had some very loud voices who have spent every waking moment from 2016 on attacking Donald Trump and attacking Christian evangelicals who support Donald Trump. Just yesterday for instance Baptist News Global published a fairly representative example of Trump Derangement Syndrome, in the form of a hysterical opinion piece by Martin Thielen describing Trump as “the most anti-Jesus President in American history” and “the second most dangerous threat to American Christianity.”

Predictably Thielen sees evangelicals as the only threat bigger than Trump, calling them hypocrites and deriding their branch of socially traditional Christianity as “dangerously toxic”. Even the langfuage he deploys is the language of a woke censor, a progressive authoritarian howling down anyone who isn’t exactly the same as them while claiming to be the champions of empathy and diversity. Laughably, he takes the only branch of Christianity that is growing, and claims that it is responsible for the dying and declining congregations people just like him preside over.

But all this inversion of reality and betrayal of traditional Christians is not expressed as a cogent series of rational points. Thielen doesn’t even bother to construct his article as an essay. It is instead simply an outraged howl showing a total fanatical commitment to every single lie that has ever been issued by the Democrat Party or by Never Trumpers about the object of their loathing. Thiel asks why evangelicals aren’t as offended by Trump as he is. After the tiresome invocation of the pussy grab quote he continues a rhetorical series of increasingly unhinged accusations masquerading as true points. Why aren’t evangelicals offended by:

“By a jury of his peers finding him liable sexual assault? By his rampant sexism? By his lack of character? By his lack of decency? By his endless lies? By his criminality? By his threats to democracy? By his admiration of dictators? By his mocking of disabled persons, POWs and victims of sexual assault? By his frightening language about immigrants being “vermin” and people who are “poisoning our blood”? By his fearmongering? By his hatred? By his chronic anger and rage? By his politics of revenge and retribution? By his racism? By his pathological narcissism? By his lack of any evidence of Christian faith, morals and values.”

It doesn’t occur to Betrayal Christians like Thiel that Real Christians might not see the things he sees, because the things he sees aren’t real. Because they are distortions and lies, or because they take metaphorical comment as real, or because they take comments deliberately at their worst and out of context, or because they refer to accusations that only represent HIS hate and the hate that people like him have towards anyone who challenges them. Fearmongering? That’s wicked and un-Christian…but not when you apply it to Trump in ways that prompt assassination attempts? Not when you decide that everyone evangelical, or MAGA, or white, or Republican, is sub-human?

All this was written after rhetoric like it prompted a fellow lunatic to fire shots at Trump and kill an innocent man in Trump’s audience. But the moderate Christian Thiel still writes this self-blind trash, this stuff which is more directly linked to violence and hate than anything Trump has ever said.

People like Thiel in the allegedly Christian churches, just like people such as Robert Reich in politics, do not see that they are the ones filled with hate, and they are the ones most likely to take authoritarian measures to express that hate.

And they have that blindness because they are NOT Christians themselves. They serve the religion of Woke. They serve Globalist idols. They just do it from with the cover of a claimed Christian identity. It’s no more real than a man putting on a dress and claiming to be a woman. Only its more cynical. Some of those are genuinely tortured by a mental illness. Pretend Christians who spend all their time attacking real Christians and all their energy supporting globalist causes, are more like people who put on the uniform of a nation they wish to betray.

The churches have a thousand Benedict Arnold’s at their head.

Look at another ‘moderate’ Christian like the Jesuit James T. Keane. Keane also hates Donald Trump. He also hates traditional Christians and Christians brave and honest enough to oppose progressive orthodoxy. In 2020 Keane celebrated the excommunication of Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò in an article in America The Jesuit Review. Keane too shows all the standard prejudices. Vigano, who opposed LGBTQ+ activism and had accused the Pope of being aware of child abuse, was described as a spreader of conspiracy theories (with no attempt to investigate the claims). But the entire article makes it clear that the real crime was writing a supportive letter addressed to Donald Trump. That, today, counts as heresy for Woke Catholics.

Or how about those Christians leaping to defend the Olympic games, tell us that no reference to the Last Supper was intended, and gaslighting us all in defense of an event that deliberately mocked their supposed faith? It’s curious that these are the leading Christians who never speak up when ancient Christian communities in the Middle East are destroyed, who have had nothing to say about Islamic genocides of Christians in history or happening today, who have no thoughts on the kidnap and rape of Christian girls in Nigeria or the grooming of and rape of nominally Christian British children by generations of Muslim rape gangs.

All the things that might have outraged a real Christian a century ago, do not outrage them. Why is that?

All the thing that truly threaten Christian populations do not frighten them. Why is that?

All the things that do outrage real morality and do threaten real Christians are things they tell us to love and understand and praise. Why is that?

The truth is that professional Establishment Christians have been as much on the other side, as professional Establishment conservatives have. Even now they are telling us that anyone who defends us is a racist, a bigot, a far right threat. Even now they are telling us that the enemies they let into our society are actually our friends. Even now they seem caring and compassionate only to people who invade our shores or groom our kids, with no care or compassion left for us. Even now they tell us that we should respect those who offer no respect to us, and protect those who only seem to mean us harm.

Chad Klinger

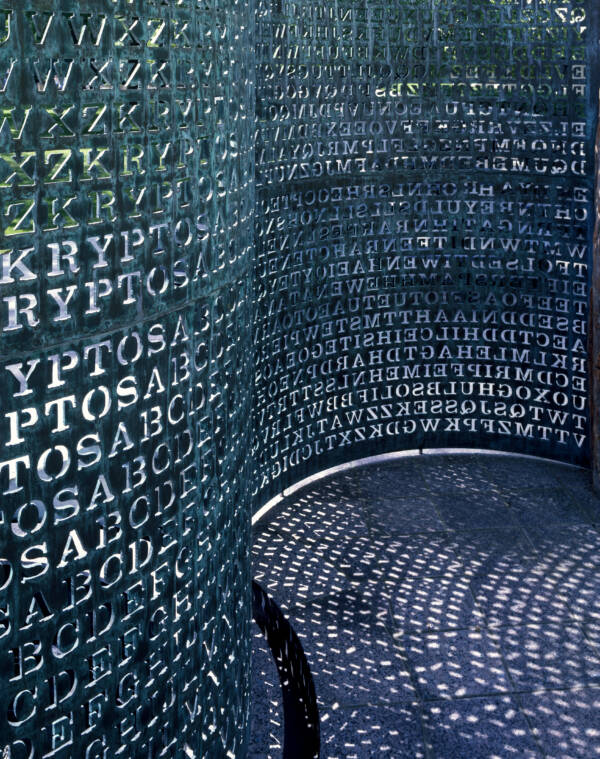

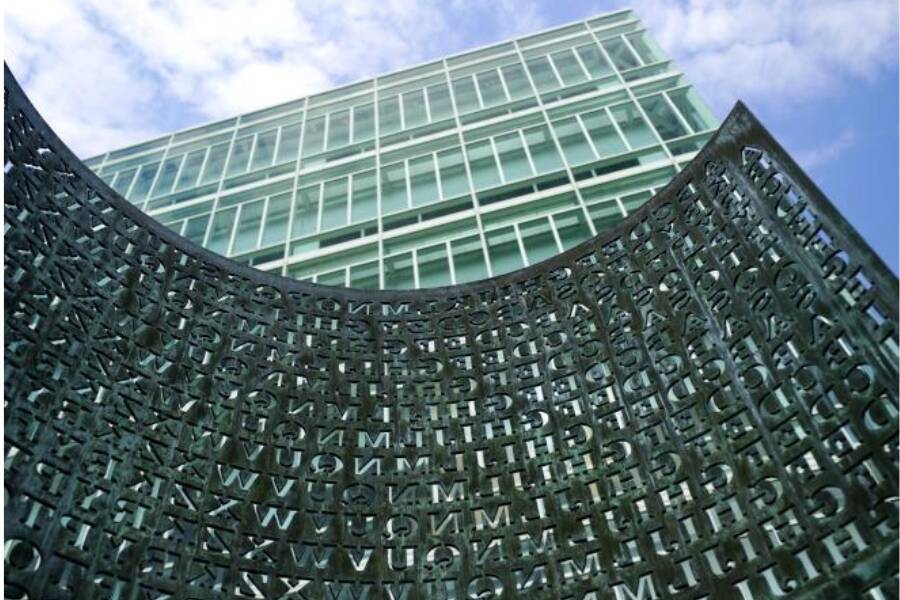

TwitterKryptos is a massive copper sculpture comprised of coded messages — but even once they’re deciphered, the sculpture’s true message will be locked behind more puzzles.

In a courtyard outside of the entrance to the Central Intelligence Agency’s New Headquarters Building, there is a mysterious sculpture dubbed “Kryptos.” Installed in 1990 by artist Jim Sanborn, Kryptos is a large, wave-shaped copper sculpture containing 1,800 characters that at first glance seem to be random, jumbled combinations

Random, however, these letters are anything but. Kryptos actually contains four distinct encrypted messages, three of which have been cracked over the course of the three decades since Kryptos was installed. The fourth has yet to be solved.

But even the sections of Kryptos’ message that have been cracked leave many wondering what the purpose of the sculpture is. In recent years, Sanborn has provided several clues as to what Kryptos’ fourth passage could mean, yet no one has been able to successfully solve this tantalizing puzzle.

Herbert James Sanborn, better known as Jim Sanborn, was born in Washington, D.C. on Nov. 14, 1945. In 1969, he graduated from Randolph-Macon College with a double major in art history and sociology, later receiving his Master’s degree in sculpture from Pratt Institute in 1971.

National Museum of Nuclear Science & HistoryArtist Jim Sanborn.

Sanborn’s works have been featured in a number of prominent and prestigious museums, including the High Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Sanborn has also produced work for several institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and, most famously, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

In 1990, Sanborn presented the CIA with a piece called “Kryptos” — a Greek word for “hidden.” And as its name would suggest, Kryptos’ meaning has remained hidden ever since.

Jim Sanborn wrote the messages in Kryptos himself. These messages are obscured by a series of increasingly elaborate coded messages. At the time, only Sanborn and former CIA Director William H. Webster had the solution to the sculpture’s encrypted messages.

“Everyone wants to know what it says,” Sanborn told the Los Angeles Times in 1991. “They’re out there all the time. There are groups of dark-suited people pointing at it and getting down on their knees, trying to figure out what it says. Some take photographs. One guy copied the whole thing down with pencil and paper.”

Sanborn said at the time that a “friend of friend” told him CIA operatives had been growing frustrated with their inability to crack the code, even going so far as to send copies of the message to agents at the National Security Agency (NSA) to try and decipher it using the NSA’s Cray supercomputer.

Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty ImagesSanborn expected Kryptos’ fourth passage to be solved within a decade.

According to Sanborn, the sculpture’s message deals with the CIA tradition of secrecy on several levels. It includes a system of ciphers devised by the 16th-century French cryptographer Blaise de Vigenère, known as a Vigenère table, among other codes which Sanborn created with the help of retired CIA cryptographer Edward Scheidt.

“He developed something that really stumped them out there,” Sanborn said. “Parts can be deciphered in a matter of weeks or months, but other parts might never be deciphered without the knowledge that Webster has. He has the key to the code, and he can easily figure the whole thing.”

Of course, the difficulty of cracking the codes embedded in Kryptos have only added to the sculpture’s notoriety. And over the years since its introduction, significant chunks of the sculpture’s message have been cracked — though the fourth section’s translation has remained elusive.

It took about eight years for someone to come forward and say they had solved part of Kryptos’ message. In 1998, CIA physicist David Stein called a meeting to announce that he had solved the first three passages of the sculpture’s puzzling message.

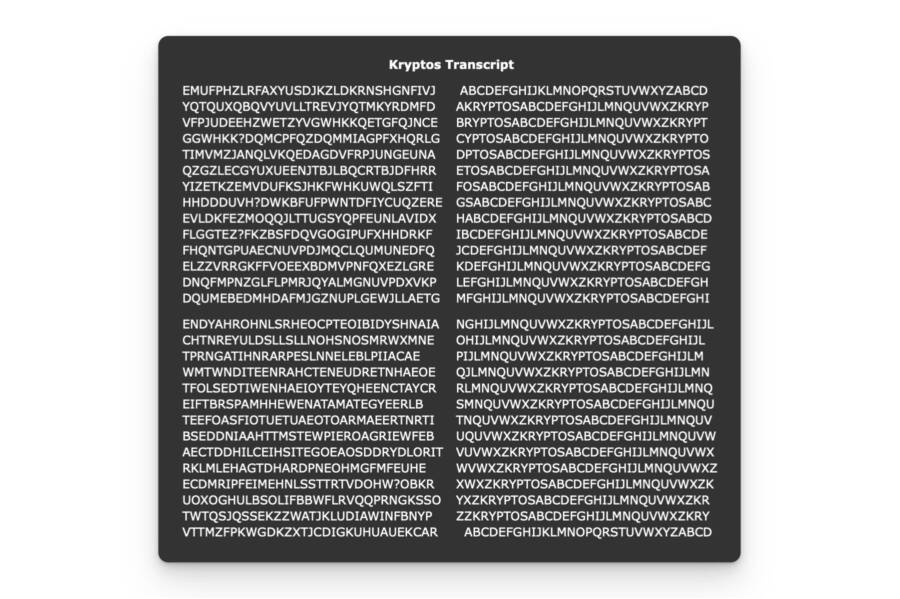

Karl Wang/University of California San DiegoA transcript of Kryptos’ message.

According to Smithsonian, around 250 people showed up to hear what Stein had found using just “pencil and paper alone.” Around the same time, a computer scientist named Jim Gillogly created computer programs to help crack the code, which is composed of classic ciphers, plus a few odd spelling errors and extra characters Sanborn intentionally left in to throw off codebreakers.

The first passage of Kryptos reads, “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of inqlusion.”

The second passage is a fair bit longer, reading in full:

It was totally invisible Hows that possible? They used the Earths magnetic field X

The information was gathered and transmitted undergruund to an unknown location X

Does Langley know about this? They should Its buried out there somewhere X

Who knows the exact location? Only WW This was his last message X

Thirty eight degrees fifty seven minutes six point five seconds north

Seventy seven degrees eight minutes forty four seconds west X

Layer two

“WW” in this passage is a direct reference to Webster. The third passage, also rather lengthy, includes another reference, this time to Egyptologist Howard Carter, the man who opened King Tutankhamen’s tomb.

It reads:

Slowly desparatly slowly the remains of passage debris that encumbered the lower part of the doorway was removed with trembling hands i made a tiny breach in the upper left hand corner and then widening the hole a little i inserted the candle and peered in the hot air escaping from the chamber caused the flame to flicker but presently details of the room within emerged from the mist X

Can you see anything q

TwitterSanborn has provided three clues to help solve Kryptos’ fourth passage, in 2010, 2014, and 2020.

Sanborn has said that the mystery of Kryptos has lasted much longer than he originally expected. Initially, he assumed the first three passages would be solved in the matter of a few years, and the fourth, most difficult passage within a decade. But three decades on, the meaning of the fourth passage is still a mystery, and Sanborn, now in his mid-70s, has had to consider that the mystery may outlive him.

At one point, he even considered auctioning off the solution and donating the money to climate research. Then, in January 2020, Sanborn offered up another clue to try and help potential codebreakers solve the puzzle. He had done the same thing in 2010 and 2014, but the 2020 clue, he said, would be the last.

Surprisingly, the fourth section of Kryptos is actually the shortest one, coming in at just 97 characters. That hasn’t made it any easier to crack, however. In fact, its brevity “could, in itself, present a decryption challenge,” Edward Scheidt, the cryptographer who helped Sanborn devise the code, told The New York Times.

To further add to the difficulty of Kryptos’ fourth passage, the text in this section also uses what’s known as a masking technique, further obscuring the message. It’s not even entirely clear what masking technique Sanborn and Scheidt used.

Wikimedia CommonsSeveral rocks and pieces of wood block the full text of Kryptos in photographs, making it more difficult to decipher.

Sanborn has received countless emails and letters over the years from prospective codebreakers, each hoping that they had finally solved the puzzle, but of course none of them had. As time went on, Sanborn decided to provide a few clues to guide would-be cryptographers.

The first clue came in 2010. It was a single word, “BERLIN,” which makes up the 64th through the 69th positions in the final passage. In 2014, Sanborn revealed the word “CLOCK” occupied spots 70 through 74.

The final clue, at positions 26 through 34, is “NORTHEAST.” In the now three years since Sanborn revealed the clue, the puzzle has still not been solved.

Even if it is, more puzzles await. As Sanborn explained, deciphering the code is only one part of the puzzle.

“They will be able to read what I wrote, but what I wrote is a mystery itself,” Sanborn said. “There are still things they have to discover once it’s deciphered. There are things in there they will never discover the true meaning of. People will always say, ‘What did he mean by that?’ What I wrote out were clues to a larger mystery.”