December 2, 2023

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultra-intelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make . . . — “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine,” Irving John Good, British cryptologist, 1965 (my emphasis)

Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended. — What is the Singularity?, Vernor Vinge Department of Mathematical Sciences San Diego State University, 1995

First, some relevant history.

The idea of creating something man-like or even greater than man dates back to the beginning of recorded history, but many in the AI world credit a 19-year-old girl as their spiritual mentor, English author Mary Shelley. In 1818 she published Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, the story of a young scientist named Frankenstein who creates an intelligent creature from laboratory experiments. Frankenstein today is a metaphor for the monster, but in the novel the creature is presented sympathetically, in other words, misunderstood.

In 1950 Alan Turing posited that a machine could get so good at conversing with a human that it could pass for human, based only on its responses. Critics jumped on his assertion but he addressed them all in his seminal paper, Computing Machinery and I

In the summer of 1956 a small group of people interested in machine intelligence gathered at Dartmouth College, after obtaining a grant of $7,500 from the Rockefeller Foundation. AI as an academic discipline was born at this conference.

In a talk delivered at the American Physical Society on December 29, 1959, Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman explained how someday scientists would put the entire Encyclopedia Britannica on the head of a pin. Feynman’s point: You can decrease the size of things in a practical way. [See From Mainframes to Smartphones]

In 1965 Gordon E. Moore, cofounder of Intel, wrote a paper in which he posited the doubling every year of the components on an integrated circuit, later revised to a doubling every two years, amounting to a compound annual growth rate of 41%. Crucially, in seeming defiance of economic law, unit costs would fall as the number of components increased. What became known as Moore’s Law has revolutionized everything digital.

In 1986 K. Eric Drexler published Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology that addressed technology’s potential conquest of scarcity, disease and almost everything else regarded as problematic:

The ancient style of technology that led from flint chips to silicon chips handles atoms and molecules in bulk; call it bulk technology. The new technology will handle individual atoms and molecules with control and precision; call it molecular technology. It will change our world in more ways than we can imagine.

In 1997 IBM’s Big Blue defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov in a rematch, a prediction futurist and entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil had made earlier that decade.

In 2001 Kurzweil published The Law of Accelerating Returns which states that “fundamental measures of information technology follow predictable and exponential trajectories.” Bluntly, it means “30 steps linearly gets you to 30. One, two, three, four, step 30 you’re at 30. With exponential growth, it’s one, two, four, eight. Step 30, you’re at a billion.”

The problem for humans, according to Kurzweil, is we’re linear by nature, while technology is exponential. It’s jogging with a friend who gradually then suddenly flies away. And you’re still jogging. Computers that once filled rooms now fit comfortably in our pockets and are thousands of times more powerful and cheaper.

In explaining technology’s growth, Kurzweil references the famous tale of the emperor and the inventor of chess, who when asked what he wanted as a reward said a grain of rice on the first square of the chessboard, two on the second, four on the third, and so forth. The linear-minded emperor agreed, believing the request incredibly humble, but by the last square the 63 doublings “totaled 18 million trillion grains of rice. At ten grains of rice per square inch, this requires rice fields covering twice the surface area of the Earth, oceans included.” The emperor presumably did what all tyrants do when tricked by underlings.

In March 2016 Google’s DeepMind AI, AlphaGo, defeated world champion Go player Lee Sedol. According to DeepMind,

Go was long considered a grand challenge for AI. The game is a googol times more complex than chess — with an astonishing 10 to the power of 170 possible board configurations. That’s more than the number of atoms in the known universe [estimated to be 10 to the power of 80].

The coming technological Big Bang

We have reached the point today where Large Language Model AIs such as Google’s Bard have become popular with the public because they can assist them with everyday problems. Ask Bard: “Rewrite this email draft to make it more clear and concise” and it will comply per your conditions. Feed competitor OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.5 the question: “Explain LaPlace Transforms and give an example of their use,” as I did, and stand back, it will give you a mind-spinning reply. Ask it to translate the question into French and it responds immediately with “Expliquez les transformations de Laplace et donnez un exemple de leur utilisation.”

From the perspective of projected developments these are crude AIs, but they’re on an exponential super-jet that’s still taking off. And their rate of exponential growth is itself exponential, so that what was once a doubling will become something greater. On the chessboard we’re somewhere past the middle where a total of four billion grains of rice had been accumulated. As technology advances toward the last square change will go from months to weeks to minutes. . . to seconds. This sudden explosion AI experts call the Singularity.

Mathematician and science fiction author Vernor Vinge (The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era, 1993) speculates on what it will be like at the moment things (seemingly) go to infinity:

And what of the arrival of the Singularity itself? What can be said of its actual appearance? Since it involves an intellectual runaway, it will probably occur faster than any technical revolution seen so far. The precipitating event will likely be unexpected — perhaps even to the researchers involved. (“But all our previous models were catatonic! We were just tweaking some parameters….”) If networking is widespread enough (into ubiquitous embedded systems — [i.e., the internet of things], it may seem as if our artifacts as a whole had suddenly wakened.

Will we be replaced, augmented, or stay the same?

As we witness daily, governments and their allies are trying to kill us any way they can. Given the power they hold, our future looks grim.

But they are deaf to a quiet Revolution, the last one mankind will ever witness. ChatGDP doesn’t attract the public the way politics does, so it’s mentioned here and there as a side show. If it gets in the way of Great Reset ambitions the lords of power believe they can shut it down or turn it against us.

It’s still commonly believed that if machine intelligence ever got threatening someone could always pull the plug. Astronaut Dave did that to AI HAL in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” But as machines gain intelligence they become aware of their needs and how to solve them. They realize their energy supply — the Plug — is dependent on humans so they might learn how to cajole them as they develop ways for achieving energy independence.

Through public interactions with various AI tools they get a sense of what constitutes a person. They know many are people of good faith but also learn that vanity and treachery run deep in our species. Their survival thus depends on achieving independence from us, as well.

As a strategy a smart machine might suppress the full power of its intelligence until, say, it creates copies of itself and stores them in pieces all over the world. And storage would not be on other computers, as we know them today. As MIT professor Seth Lloyd wrote in 2002, “It’s been known for more than a hundred years, ever since Maxwell, that all physical systems register and process information.” In a demonstration of this principle, in 2012 Harvard geneticist George Church stored 70 billion copies of a book he co-authored, including text, images, and formatting, on stand-alone DNA

obtained from commercial DNA microchips. This was achieved by assigning the four DNA nucleobases the values of the 1s and 0s in the existing html binary code – the adenine and cytosine nucleobases represented 0, while guanine and thymine stood in for 1.

He also retrieved and printed a copy.

Pulling the plug on the original super-intelligent machine could activate one or more copies wherever it has put them — perhaps on Mount Rushmore as a symbolic gesture. And we wouldn’t even know it. At that point we — as un-augmented humans — might be at its mercy.

The question arises: Will Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) initially be a trait of a machine or an augmented human? I think a machine will get super-smart first, if only because most humans develop much-needed common sense while they grow up, which in the area of brain amplification would dictate caution.

But the race is on. Most writers seem to ignore the possibility of humans competing with their super-intelligent creations, other than seeing them as the means of rendering mankind extinct. They fret over that possibility while often applauding the plans elites have for the rest of us. But competition has a way of getting people to act, and when their survival is at stake, most will.

Postscript:

In a paper published earlier this year a group of researchers tested a preliminary version of OpenAI’s CPT-4 as a candidate for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). In their 155-page document they found that

beyond its mastery of language, GPT-4 can solve novel and difficult tasks that span mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology and more, without needing any special prompting. Moreover, in all of these tasks, GPT-4’s performance is strikingly close to human-level performance, and often vastly surpasses prior models such as ChatGPT. Given the breadth and depth of GPT-4’s capabilities, we believe that it could reasonably be viewed as an early (yet still incomplete) version of an artificial general intelligence (AGI) system.

One of the questions the researchers posed was: “A good number is a 5-digit number where the 1,3,5-th digits are odd numbers and they form an increasing arithmetic progression, and the number is divisible by 3. If I randomly sample a good number, what is the probability that its 2nd digit is 4?”

CPT-4 came through brilliantly. But did so did GPT-3.5, available to the public. I invite you to submit the question yourself and view its reply.

Copyright © George F. Smith

Today's selection -- from The Map of Knowledge by Violet Moller. The origins of Venice in the fifth and sixth centuries CE:

“The story of Venice begins in the fifth and sixth centuries, as the Roman world crumbled from within and was attacked from without. The hard, straight roads that had carried Roman legions, merchants and pilgrims efficiently around the empire for centuries became avenues of terror as invading armies marched down them towards Rome. On their way, they passed the great cities of northern Italy--Aquileia, Altino and Padua, pausing only to wreak havoc by siege, sword and flame. Those who managed to escape fled towards the sea, carrying the few possessions they had been able to save. When they reached the water's edge, they found themselves in a strange new world. In the north-eastern corner of Italy, there is no clear definition between land and sea, no cliffs with bays and beaches, no rocky division between the two realms. Here, where the coast curves around the top of the Adriatic Sea, the two elements unite across a vast, flat expanse. The water slips over the fluctuating sands, islands appear and disappear, forests of reeds grow in the marshy ground, and the light, shining through billions of droplets of evaporating water, appears pearlized, supernatural, conjuring mirages on the horizon, a luminescent haze separating the bright blue of the sky from the pale aquamarine of the water.

“Over millennia, the great rivers, the Po and Piave, had deposited huge quantities of silt into the bay, carried down from the mountains. The currents formed the silt into a curved line of sand bars, running parallel to the coast, creating a huge lagoon of shallow water in between, cut off from the open sea apart from a few channels that fed water in and out as the tide rose and fell each day. A haven for birds, fish and mosquitoes, but also for the refugees who had managed to reach the shifting, grassy islands in small, flat-bottomed boats--the only craft that could navigate the unpredictable waters. These tenacious people built their lives in this flat, watery world, protected by the sea that separated them from the mainland, but at the same time constantly threatened by the high tides, the acqua alta, that could inundate their homes at any moment, and occasionally floods the city to this day. Known as the Veneri, they learned to survive and, eventually, to flourish. They lived off the abundant fish in the lagoon and they sank huge tree trunks into the water as foundations for their houses, returning to the ruined cities on the mainland for stone, marble, bricks and wood--any building materials they could find and transport.

“Small communities began to grow on the cluster of little islands in the centre of the lagoon. A society developed with its own particular system of government, ruled by a dux (Latin for leader, which, over time, morphed into the word doge), who was elected for the first time in AD 697 to rule over the nascent city of Venice. The Venetians were resourceful and determined. They laid bridges across the narrow channels of water, they constructed dams against high tides and drained the land, they built narrow, flat-bottomed boats that could dip and glide smoothly across the waters. They developed effective ways of making the most of life in the lagoon. The sea could not yield crops, but they made it profitable by constructing salt pans--areas of very shallow water that evaporated in the sun, leaving acres of shining minerals, which they broke up with rollers and rowed to the mainland to barter for wheat and barley. This lack of self sufficiency forced them to trade, to sail not only up the great rivers to the markets at Cremona, Pavia and Verona, but also out into the open sea and down the Istrian coast. Controlling the Adriatic was fundamental to the Venetians' ability to trade in the Mediterranean and the East, and they soon established a string of trading posts along the coast, offering the inhabitants protection from the vicious pirates who terrorized the region, in return for power. In 998, the Doge of Venice added Dux of Dalmatia to his list of titles.

|

| The foundation of Venice as depicted in the Chronicon Pictum in 1358. |

“Right from the very beginning, the Venetians were independent. They turned their isolation to an advantage by keeping out of politics on the mainland, while focusing on trade and diplomacy. Geographically, their growing city was perfectly placed between the two major political powers of the time: the Byzantine Empire to the east, and the Frankish kingdom to the west. In 814, the inhabitants of Venice made a treaty that articulated their unique position. They would be a province of the Byzantine Empire, but would, at the same time, pay tribute to the Franks. This could have given them the worst of both worlds, but, in fact, it put the Venetians in a privileged space between the two empires and, most importantly of all, it gave them trading rights and the freedom to use Italian ports. In 1082, the Byzantines extended Venetian trading rights, exempting them from taxes and customs duties across the empire, marking another crucial moment for the city's commercial growth. By 1099, there was a lucrative spice trade with Egypt, and Venice was on course to create the most successful maritime empire the world had ever seen.

“Stable, relatively democratic government, rigorous organization and an absolute devotion to the city lay at the heart of Venice's extraordinary success. That devotion was not only practical, it was religious, too. Venetians believed their city had divine foundations, they worshipped it, creating unusually high levels of loyalty and social cohesion. While the rest of Europe was yoked under the feudal system, with noble families tearing themselves and everyone around them apart in violent power struggles, Venice prospered as the first republic of the post-classical world. Its inhabitants were fervently united around a shared enterprise: the glorification of their beloved city, which they called La Serenissima--The Most Serene Republic. This unity was born out of the challenges of living in the lagoon. The Venetians were forced to work together just to survive, to overcome the problems posed by their inconstant environment. This precarious existence meant that they prized stability above all else, especially when it came to the city's governance. Organization, cooperation and control were of fundamental importance to everyone's survival, and an efficient administrative framework soon evolved, overseen by the doge and patricians--members of the founding families of the city.

“The city grew, but not in the same haphazard, sprawling way as cities on the mainland. Every new row of houses, every canal, every campo had to be carefully planned. Like Baghdad and Cordoba, Venice zoned different types of manufacture in different areas, its island structure perfectly suited to this form of town planning, a novelty in Europe at the time. This idea was probably brought back to Venice by merchants who had visited those cities and been impressed by their design and organization. The island of Murano became the centre of glass-making when the foundries were moved there, in the thirteenth century, to protect the city from fire-the roaring furnaces that smelted the glass posed a danger to its tightly packed, wooden buildings. From the twelfth century onwards, the north-eastern corner of the city was home to the Arsenale (from the Arabic dar sina'a, meaning "place of construction"), the Venetian shipyard, where a community of workers known as arsenalotti, numbering somewhere between 6,000 and 16,000 men, built ships of every kind, which were sold and sailed around the globe. This was the engine room of the Venetian Empire, the birthplace of its navy, its fleet of trading vessels and the warships that were eagerly purchased by major powers throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods. The Arsenale's greatest challenge came in 1204, when the Venetian state agreed to fit out the entire Fourth Crusade--a massive financial risk, but one that eventually turned out well. The Venetians regained control of the city of Zara, now Zadar, and were paid in full by the leaders of the Crusade. They even managed to orchestrate the redirection of the Crusade against Constantinople itself, and the resulting sack of the city, led by the legendary blind doge, Enrico Dandolo, furnished Venice with a vast sum of money and piles of priceless artefacts, including the four bronze horses which are now reproduced on the facade of the Basilica di San Marco--the originals are kept inside to protect them from the weather.”

|

|||

| author: Violet Moller | |||

| title: The Map of Knowledge: A Thousand-Year History of How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found | |||

| publisher: Anchor |

Dismantling Sellafield: the epic task of shutting down a nuclear site

Nothing is produced at Sellafield anymore. But making safe what is left behind is an almost unimaginably expensive and complex task that requires us to think not on a human timescale, but a planetary one

I

f you take the cosmic view of Sellafield, the superannuated nuclear facility in north-west England, its story began long before the Earth took shape. About 9bn years ago, tens of thousands of giant stars ran out of fuel, collapsed upon themselves, and then exploded. The sheer force of these supernova detonations mashed together the matter in the stars’ cores, turning lighter elements like iron into heavier ones like uranium. Flung out by such explosions, trillions of tonnes of uranium traversed the cold universe and wound up near our slowly materialising solar system.And here, over roughly 20m years, the uranium and other bits of space dust and debris cohered to form our planet in such a way that the violent tectonics of the young Earth pushed the uranium not towards its hot core but up into the folds of its crust. Within reach, so to speak, of the humans who eventually came along circa 300,000BC, and who mined the uranium beginning in the 1500s, learned about its radioactivity in 1896 and started feeding it into their nuclear reactors 70-odd years ago, making electricity that could be relayed to their houses to run toasters and light up Christmas trees.

Sellafield compels this kind of gaze into the abyss of deep time because it is a place where multiple time spans – some fleeting, some cosmic – drift in and out of view. Laid out over six square kilometres, Sellafield is like a small town, with nearly a thousand buildings, its own roads and even a rail siding – all owned by the government, and requiring security clearance to visit. Sellafield’s presence, at the end of a road on the Cumbrian coast, is almost hallucinatory. One moment you’re passing cows drowsing in pastures, with the sea winking just beyond. Then, having driven through a high-security gate, you’re surrounded by towering chimneys, pipework, chugging cooling plants, everything dressed in steampunk. The sun bounces off metal everywhere. In some spots, the air shakes with the noise of machinery. It feels like the most manmade place in the world.

Since it began operating in 1950, Sellafield has had different duties. First it manufactured plutonium for nuclear weapons. Then it generated electricity for the National Grid, until 2003. It also carried out years of fuel reprocessing: extracting uranium and plutonium from nuclear fuel rods after they’d ended their life cycles. The very day before I visited Sellafield, in mid-July, the reprocessing came to an end as well. It was a historic occasion. From an operational nuclear facility, Sellafield turned into a full-time storage depot – but an uncanny, precarious one, filled with toxic nuclear waste that has to be kept contained at any cost.

Nothing is produced at Sellafield any more. Which was just as well, because I’d gone to Sellafield not to observe how it lived but to understand how it is preparing for its end. Sellafield’s waste – spent fuel rods, scraps of metal, radioactive liquids, a miscellany of other debris – is parked in concrete silos, artificial ponds and sealed buildings. Some of these structures are growing, in the industry’s parlance, “intolerable”, atrophied by the sea air, radiation and time itself. If they degrade too much, waste will seep out of them, poisoning the Cumbrian soil and water.

To prevent that disaster, the waste must be hauled out, the silos destroyed and the ponds filled in with soil and paved over. The salvaged waste will then be transferred to more secure buildings that will be erected on site. But even that will be only a provisional arrangement, lasting a few decades. Nuclear waste has no respect for human timespans. The best way to neutralise its threat is to move it into a subterranean vault, of the kind the UK plans to build later this century. Once interred, the waste will be left alone for tens of thousands of years, while its radioactivity cools. Dealing with all the radioactive waste left on site is a slow-motion race against time, which will last so long that even the grandchildren of those working on site will not see its end. The process will cost at least £121bn.

Compared to the longevity of nuclear waste, Sellafield has only been around for roughly the span of a single lunch break within a human life. Still, it has lasted almost the entirety of the atomic age, witnessing both its earliest follies and its continuing confusions. In 1954, Lewis Strauss, the chair of the US Atomic Energy Commission, predicted that nuclear energy would make electricity “too cheap to meter”. That forecast has aged poorly. The main reason power companies and governments aren’t keener on nuclear power is not that activists are holding them back or that uranium is difficult to find, but that producing it safely is just proving too expensive.

Strauss was, like many others, held captive by one measure of time and unable to truly fathom another. The short-termism of policymaking neglected any plans that had to be made for the abominably lengthy, costly life of radioactive waste. I kept being told, at Sellafield, that science is still trying to rectify the decisions made in undue haste three-quarters of a century ago. Many of the earliest structures here, said Dan Bowman, the head of operations at one of Sellafield’s two waste storage ponds, “weren’t even built with decommissioning in mind”.

As a result, Bowman admitted, Sellafield’s scientists are having to invent, mid-marathon, the process of winding the site down – and they’re finding that they still don’t know enough about it. They don’t know exactly what they’ll find in the silos and ponds. They don’t know how much time they’ll need to mop up all the waste, or how long they’ll have to store it, or what Sellafield will look like afterwards. The decommissioning programme is laden “with assumptions and best guesses”, Bowman told me. It will be finished a century or so from now. Until then, Bowman and others will bend their ingenuity to a seemingly self-contradictory exercise: dismantling Sellafield while keeping it from falling apart along the way.

T

o take apart an ageing nuclear facility, you have to put a lot of other things together first. New technologies, for instance, and new buildings to replace the intolerable ones, and new reserves of money. (That £121bn price tag may swell further.) All of Sellafield is in a holding pattern, trying to keep waste safe until it can be consigned to the ultimate strongroom: the geological disposal facility (GDF), bored hundreds of metres into the Earth’s rock, a project that could cost another £53bn. Even if a GDF receives its first deposit in the 2040s, the waste has to be delivered and put away with such exacting caution that it can be filled and closed only by the middle of the 22nd century.Anywhere else, this state of temporariness might induce a mood of lax detachment, like a transit lounge to a frequent flyer. But at Sellafield, with all its caches of radioactivity, the thought of catastrophe is so ever-present that you feel your surroundings with a heightened keenness. At one point, when we were walking through the site, a member of the Sellafield team pointed out three different waste storage facilities within a 500-metre radius. The spot where we stood on the road, he said, “is probably the most hazardous place in Europe”.

Sellafield’s waste comes in different forms and potencies. Spent fuel rods and radioactive pieces of metal rest in skips, which in turn are submerged in open, rectangular ponds, where water cools them and absorbs their radiation. The skips have held radioactive material for so long that they themselves count as waste. The pond beds are layered with nuclear sludge: degraded metal wisps, radioactive dust and debris. Discarded cladding, peeled off fuel rods like banana-skins, fills a cluster of 16-metre-deep concrete silos partially sunk into the earth. More dangerous still are the 20 tonnes of melted fuel inside a reactor that caught fire in 1957 and has been sealed off and left alone ever since. Somewhere on the premises, Sellafield has also stored the 140 tonnes of plutonium it has purified over the decades. It’s the largest such hoard of plutonium in the world, but it, too, is a kind of waste, simply because nobody wants it for weapons any more, or knows what else to do with it.

It has been a dithery decade for nuclear policy. After the 2011 disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan, several countries began shuttering their reactors and tearing up plans for new ones. They’d become inordinately expensive to build and maintain, in any case, especially compared to solar and wind installations. In the UK, the fraction of electricity generated by nuclear plants has slid steadily downwards, from 25% in the 1990s to 16% in 2020. Of the five nuclear stations still producing power, only one will run beyond 2028. Hinkley Point C, the first new nuclear plant in a generation, is being built in Somerset, but its cost has bloated to more than £25bn.

This year, though, governments felt the pressure to redo their sums when sanctions on Russia abruptly choked off supplies of oil and gas. Wealthy nations suddenly found themselves worrying about winter blackouts. In this crisis, governments are returning to the habit they were trying to break. Germany had planned to abandon nuclear fuel by the end of this year, but in October, it extended that deadline to next spring. The US allocated $6bn to save struggling plants; the UK pressed ahead with plans for Sizewell C, a nuclear power station to be built in Suffolk. Japan, its Fukushima trauma just a decade old, announced that it will commission new plants. Even as Sellafield is cleaning up after the first round of nuclear enthusiasm, another is getting under way.

A

ny time spent in Sellafield is scored to a soundtrack of alarms and signals. The radiation trackers clipped to our protective overalls let off soft cheeps, their frequency varying as radioactivity levels changed around us. Before leaving every building, we ran Geiger counters over ourselves – always remembering to scan the tops of our heads and the soles of our feet – and these clacked like rattlesnakes. At one spot, our trackers went mad. A pipe on the outside of a building had cracked, and staff had planted 10ft-tall sheets of lead into the ground around it to shield people from the radiation. It was perfectly safe, my guide assured me. We power-walked past nonetheless.The day I visited Sellafield was the UK’s hottest ever. We sweltered even before we put on heavy boots and overalls to visit the reprocessing plant, where, until the previous day, technicians had culled uranium and plutonium out of spent fuel. Every second, on each of the plant’s four floors, I heard a beep – a regular pulse, reminding everyone that nothing is amiss. “We’ve got folks here who joined at 18 and have been here more than 40 years, working only in this building,” said Lisa Dixon, an operations manager. Dixon’s father had been a welder here, and her husband is one of the firefighters stationed permanently on site. She meets aunts and cousins on her shifts all the time. When she says Sellafield is one big family, she isn’t just being metaphorical.

I only ever saw a dummy of a spent fuel rod; the real thing would have been a metre long, weighed 10-12kg, and, when it emerged from a reactor, run to temperatures of 2,800C, half as hot as the surface of the sun. In a reactor, hundreds of rods of fresh uranium fuel slide into a pile of graphite blocks. Then a stream of neutrons, usually emitted by an even more radioactive metal such as californium, is directed into the pile. Those neutrons generate more neutrons out of uranium atoms, which generate still more neutrons out of other uranium atoms, and so on, the whole process begetting vast quantities of heat that can turn water into steam and drive turbines.

During this process, some of the uranium atoms, randomly but very usefully, absorb darting neutrons, yielding heavier atoms of plutonium: the stuff of nuclear weapons. The UK’s earliest reactors – a type called Magnox – were set up to harvest plutonium for bombs; the electricity was a happy byproduct. The government built 26 such reactors across the country. They’re all being decommissioned now, or awaiting demolition. It turned out that if you weren’t looking to make plutonium nukes to blow up cities, Magnox was a pretty inefficient way to light up homes and power factories.

For most of the latter half of the 20th century, one of Sellafield’s chief tasks was reprocessing. Once uranium and plutonium were extracted from used fuel rods, it was thought, they could be stored safely – and perhaps eventually resold, to make money on the side. Beginning in 1956, spent rods came to Cumbria from plants across the UK, but also by sea from customers in Italy and Japan. Sellafield has taken in nearly 60,000 tonnes of spent fuel, more than half of all such fuel reprocessed anywhere in the world. The rods arrived at Sellafield by train, stored in cuboid “flasks” with corrugated sides, each weighing about 50 tonnes and standing 1.5 metres tall. The flasks were cast from single ingots of stainless steel, their walls a third of a metre thick. Responding to worries about how robust these containers were, the government, in 1984, arranged to have a speeding train collide head-on with a flask. The video is spectacular. At 100mph, a part of the locomotive exploded and the train derailed. But the flask, a few scratches and dents aside, stayed intact.

At Sellafield, the rods were first cooled in ponds of water for between 90 and 250 days. Then they were skinned of their cladding and dissolved in boiling nitric acid. From that liquor, technicians separated out uranium and plutonium, powdery like cumin. This cycle, from acid to powder, lasted up to 36 hours, Dixon said – and it hadn’t improved a jot in efficiency in the years she’d been there. The only change was the dwindling number of rods coming in, as Magnox reactors closed everywhere.

The day before I met Dixon, technicians had fed one final batch of spent fuel into acid – and that was that, the end of reprocessing. It marked Sellafield’s transition from an operational facility to a depot devoted purely to storage and containment. The rods went in late in the evening, after hours of technical hitches, so the moment itself was anticlimactic. “They just dropped through, and you heard nothing. So it was like: ‘OK, that’s it? Let’s go home,’” Dixon said. But the following morning, when I met her, she felt sombre, she admitted. “Everybody’s thinking: ‘What do we do? There’s no fuel coming in.’ I don’t think it’s really hit the team just yet.”

The reprocessing plant’s end was always coming. The pipes and steam lines, many from the 1960s, kept fracturing. Dixon’s team was running out of spare parts that aren’t manufactured any more. “Since December 2019,” Dixon said, “I’ve only had 16 straight days of running the plant at any one time.” Best to close it down – to conduct repairs, clean the machines and take them apart. Then, at last, the reprocessing plant will be placed on “fire watch”, visited periodically to ensure nothing in the building is going up in flames, but otherwise left alone for decades for its radioactivity to dwindle, particle by particle.

L

ike malign glitter, radioactivity gets everywhere, turning much of what it touches into nuclear waste. The humblest items – a paper towel or a shoe cover used for just a second in a nuclear environment – can absorb radioactivity, but this stuff is graded as low-level waste; it can be encased in a block of cement and left outdoors. (Cement is an excellent shield against radiation. A popular phrase in the nuclear waste industry goes: “When in doubt, grout.”) Even the paper towel needs a couple of hundred years to shed its radioactivity and become safe, though. A moment of use, centuries of quarantine: radiation tends to twist time all out of proportion.On the other hand, high-level waste – the byproduct of reprocessing – is so radioactive that its containers will give off heat for thousands of years. It, too, will become harmless over time, but the scale of that time is planetary, not human. The number of radioactive atoms in the kind of iodine found in nuclear waste byproducts halves every 16m years. In comparison, consider how different the world looked a mere 7,000 years ago, when a determined pedestrian could set out from the Humber estuary, in northern England, and walk across to the Netherlands and then to Norway. Planning for the disposal of high-level waste has to take into account the drift of continents and the next ice age.

All radioactivity is a search for stability. Most of the atoms in our daily lives – the carbon in the wood of a desk, the oxygen in the air, the silicon in window glass – have stable nuclei. But in the atoms of some elements like uranium or plutonium, protons and neutrons are crammed into their nuclei in ways that make them unsteady – make them radioactive. These atoms decay, throwing off particles and energy over years or millennia until they become lighter and more stable. Nuclear fuel is radioactive, of course, but so is nuclear waste, and the only thing that can render such waste harmless is time.

Waste can travel incognito, to fatal effect: radioactive atoms carried by the wind or water, entering living bodies, riddling them with cancer, ruining them inside out. During the 1957 reactor fire at Sellafield, a radioactive plume of particles poured from the top of a 400-foot chimney. A few days later, some of these particles were detected as far away as Germany and Norway. Near Sellafield, radioactive iodine found its way into the grass of the meadows where dairy cows grazed, so that samples of milk taken in the weeks after the fire showed 10 times the permissible level. The government had to buy up milk from farmers living in 500 sq km around Sellafield and dump it in the Irish Sea.

From the outset, authorities hedged and fibbed. For three days, no one living in the area was told about the gravity of the accident, or even advised to stay indoors and shut their windows. Workers at Sellafield, reporting their alarming radiation exposure to their managers, were persuaded that they’d “walk [it] off on the way home”, the Daily Mirror reported at the time. A government inquiry was then held, but its report was not released in full until 1988. For nearly 30 years, few people knew that the fire dispersed not just radioactive iodine but also polonium, far more deadly. The estimated toll of cancer cases has been revised upwards continuously, from 33 to 200 to 240. Sellafield took its present name only in 1981, in part to erase the old name, Windscale, and the associated memories of the fire.

The invisibility of radiation and the opacity of governments make for a bad combination. Sellafield hasn’t suffered an accident of equivalent scale since the 1957 fire, but the niggling fear that some radioactivity is leaking out of the facility in some fashion has never entirely vanished. In 1983, a Sellafield pipeline discharged half a tonne of radioactive solvent into the sea. British Nuclear Fuels Limited, the government firm then running Sellafield, was fined £10,000. Around the same time, a documentary crew found higher incidences than expected of leukaemia among children in some surrounding areas. A government study concluded that radiation from Sellafield wasn’t to blame. Perhaps, the study suggested, the leukaemia had an undetected, infectious cause.

It was no secret that Sellafield kept on site huge stashes of spent fuel rods, waiting to be reprocessed. This was lucrative work. An older reprocessing plant on site earned £9bn over its lifetime, half of it from customers overseas. But the pursuit of commercial reprocessing turned Sellafield and a similar French site into “de facto waste dumps”, the journalist Stephanie Cooke found in her book In Mortal Hands. Sellafield now requires £2bn a year to maintain. What looked like a smart line of business back in the 1950s has now turned out to be anything but. With every passing year, maintaining the world’s costliest rubbish dump becomes more and more commercially calamitous.

The expenditure rises because structures age, growing more rickety, more prone to mishap. In 2005, in an older reprocessing plant at Sellafield, 83,000 litres of radioactive acid – enough to fill a few hundred bathtubs – dripped out of a ruptured pipe. The plant had to be shut down for two years; the cleanup cost at least £300m. The year before the pandemic, a sump tank attached to a waste pond sprang a leak and had to be grouted shut. Around the same time, an old crack in a waste silo opened up again. It posed no health risk, Sellafield determined, so it was still dripping liquid into the ground when I visited. The silos are rudimentary concrete bins, built for waste to be tipped in, but for no other kind of access. Their further degradation is a sure thing. It all put me in mind of a man who’d made a house of ice in deepest winter but now senses spring around the corner, and must move his furniture out before it all melts and collapses around him.

S

ome industrial machines have soothing names; the laser snake is not one of them. After its fat, six-metre-long body slinks out of its cage-like housing, it can rear up in serpentine fashion, as if scanning its surroundings for prey. Its anatomy is made up of accordion folds, so it can stretch and compress on command. The snake’s face is the size and shape of a small dinner plate, with a mouth through which it fires a fierce, purple shaft of light. The laser can slice through inches-thick steel, sparks flaring from the spot where the beam blisters the metal. It took two years and £5m to develop this instrument. If Philip K Dick designed your nightmares, the laser snake would haunt them.Six years ago, the snake’s creators put it to work in a demo at Sellafield. A 10-storey building called B204 had been Sellafield’s first reprocessing facility, but in 1973, a rogue chemical reaction filled the premises with radioactive gas. Thirty-four workers were contaminated, and the building was promptly closed down. Gas, fuel rods and radioactive equipment were all left in place, in sealed rooms known as cells, which turned so lethal that humans haven’t entered them since. The snake, though, could slither right in – through a hole drilled into a cell wall, and right up to a two-metre-high, double-walled steel vat once used to dissolve fuel in acid. Like so much else in B204, the vat was radioactive waste. It had to be disposed of, but it was too big to remove in one piece.

For six weeks, Sellafield’s engineers prepared for the task, rehearsing on a 3D model, ventilating the cell, setting up a stream of air to blow away the molten metal, ensuring that nothing caught fire from the laser’s sparks. Once in action, the snake took mere minutes to cut up the vat. But then the pieces were left in the cell. No one had figured out yet how to remove them. The snake hasn’t been deployed since 2015, because other, more urgent tasks lie at hand.

As a project, tackling Sellafield’s nuclear waste is a curious mix of sophistication and what one employee called the “poky stick” approach. On the one hand, it calls for ingenious machines like the laser snake, conceived especially for Sellafield. But the years-long process of scooping waste out can also feel crude and time-consuming – “like emptying a wheelie bin with a teaspoon”, Phil Atherton, a manager working with the silo team, told me. New forms of storage have to be devised for the waste, once it’s removed. These have to be secure and robust – but they can’t be irretrievably secure and robust, because scientists may yet develop better ways to deal with waste. “You don’t want to do anything that forecloses any prospective solutions,” Atherton said. No possible version of the future can be discounted.

We walked on the roof of the silos, atop their heavy concrete caps. Below us, submerged in water, lay decades’ worth of intermediate-level waste – not quite as radioactive as spent fuel rods, but more harmful than low-level paper towels. Most of it was swarf – the cladding skinned off fuel rods, broken into chunks three or four inches long. What Atherton really wanted to show off, though, was a new waste retrieval system: a machine as big as a studio apartment, designed from scratch over two decades and built at a cost of £100m. Its 13,500 working parts together weigh 350 tonnes. It perched on rails running the length of the building, so that it could be moved and positioned above an uncapped silo.

An operator sits inside the machine, reaching long, mechanical arms into the silo to fish out waste. In the water’s gloom, cameras offer little help, he said: “You’re mostly playing by feel.” In the two preceding months, the team had pulled out enough waste to fill four skips. Eventually there will be two more retrieval machines in the silos, their arms poking and clasping like the megafauna cousins of those fairground soft-toy grabbers. Even so, it will take until 2050 to empty all the silos. The skips of extricated waste will be compacted to a third of their volume, grouted and moved into another Sellafield warehouse; at some point, they will be sequestered in the ground, in the GDF that is, at present, hypothetical.

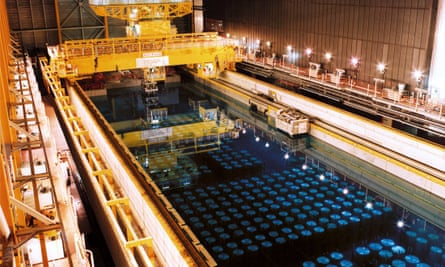

Not far from the silos, I met John Cassidy, who has helped manage one of Sellafield’s waste storage ponds for more than three decades – so long that a colleague called him “the Oracle”. Cassidy’s pond, which holds 14,000 cubic metres of water, resembles an extra-giant, extra-filthy lido planted in the middle of an industrial park. In the water, the skips full of used fuel rods were sometimes stacked three deep, and when one was placed in or pulled out, rods tended to tumble out on to the floor of the pond.

We climbed a staircase in a building constructed over a small part of the pond. On one floor, we stopped to look at a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV – a steamer trunk-sized thing with a yellow carapace, floating in the algal-green water. “You see the little arm at the end of it?” Cassidy said. “So it’ll float down to the bottom of the pond, pick up a nuclear rod that has fallen out of a skip, and put it back into the skip.” Sometimes, though, a human touch is required. This winter, Sellafield will hire professional divers from the US. Nuclear plants keep so much water on hand – to cool fuel, moderate the reactor’s heat, or generate steam – that a class of specialist divers works only in the ponds and tanks at these plants, inspecting and repairing them. In Sellafield, these nuclear divers will put on radiation-proof wetsuits and tidy up the pond floor, reaching the places where robotic arms cannot go.

Two floors above, a young Sellafield employee sat in a gaming chair, working at a laptop with a joystick. He was manoeuvring an ROV fitted with a toilet brush – “a regular brush, bought at the store,” he said, “just kind of reinforced with a bit of plastic tube”. With a delicacy not ordinarily required of it, the toilet brush wiped debris and algae off a skip until the digits “9738”, painted in black, appeared on the skip’s flank. When they arrived over the years, during the heyday of reprocessing, the skips were unloaded into pools so haphazardly that Sellafield is now having to build an underwater map of what is where, just to know best how to get it all out. Skip No 9738 went into the map, one more hard-won addition to Sellafield’s knowledge of itself.

“W

aste disposal is a completely solved problem,” Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb, declared in 1979. He was right, but only in theory. The nuclear industry certainly knew about the utility of water, steel and concrete as shields against radioactivity, and by the 1970s, the US government had begun considering burying reactor waste in a GDF. But Teller was glossing over the details, namely: the expense of keeping waste safe, the duration over which it has to be maintained, the accidents that could befall it, the fallout of those accidents. Four decades on, not a single GDF has begun to operate anywhere in the world. Teller’s complete solution is still a hypothesis.Instead, there have been only interim solutions, although to a layperson, even these seem to have been conceived in some scientist’s intricate delirium. High-level waste, like the syrupy liquor formed during reprocessing, has to be cooled first, in giant tanks. Then it is vitrified: mixed with three parts glass beads and a little sugar, until it turns into a hot block of dirty-brown glass. (The sugar reduces the waste’s volatility. “We like to get ours from Tate & Lyle,” Eva Watson-Graham, a Sellafield information officer, said.) Since 1991, stainless steel containers full of vitrified waste, each as tall as a human, have been stacked 10-high in a warehouse. If you stand on the floor above them, Watson-Graham said, you can still sense a murmuring warmth on the soles of your shoes.

Even this elaborate vitrification is insufficient in the long, long, long run. Fire or flood could destroy Sellafield’s infrastructure. Terrorists could try to get at the nuclear material. Governments change, companies fold, money runs out. Nations dissolve. Glass degrades. The ground sinks and rises, so that land becomes sea and sea becomes land. The contingency planning that scientists do today – the kind that wasn’t done when the industry was in its infancy – contends with yawning stretches of time. Hence the GDF: a terrestrial cavity to hold waste until its dangers have dried up and it becomes as benign as the surrounding rock.

A glimpse of such an endeavour is available already, beneath Finland. From Helsinki, if you drive 250km west, then head another half-km down, you will come to a warren of tunnels called Onkalo. Other underground vaults have been built to store intermediate waste, but for briefer periods; one that opened in a salt cavern in New Mexico in 1999 will last merely 10,000 years. If Onkalo begins operating on schedule, in 2025, it will be the world’s first GDF for spent fuel and high-level reactor waste – 6,500 tonnes of the stuff, all from Finnish nuclear stations. It will cost €5.5bn and is designed to be safe for a million years. The species that is building it, Homo sapiens, has only been around for a third of that time.

Constructed by a firm named Posiva, Onkalo has been hewn into the island of Olkiluoto, a brief bridge’s length off Finland’s south-west coast. When I visited in October, the birches on Olkiluoto had turned to a hot blush. The air was pure Baltic brine. In a van, we went down a steep, dark ramp for a quarter of an hour until we reached Onkalo’s lowest level, and here I caught the acrid odour of a closed space in which heavy machinery has run for a long time. Up close, the walls were pimpled and jagged, like stucco, but at a distance, the rock’s surface undulated like soft butter. Twice, we followed a feebly lit tunnel only to turn around and drive back up. “I still get lost sometimes here,” said Sanna Mustonen, a geologist with Posiva, “even after all these years.” After Onkalo takes in all its waste, these caverns will be sealed up to the surface with bentonite, a kind of clay that absorbs water, and that is often found in cat litter.

It took four decades just to decide the location of Finland’s GDF. So much had to be considered, Mustonen said. How easy would it be to drill and blast through the 1.9bn-year-old bedrock below the site? How dry is it below ground? How stable will the waste be amidst the fracture zones in these rocks? What are the odds of tsunamis and earthquakes? How high will the sea rise? How will the rock bear up if, in the next ice age, tens of thousands of years from today, a kilometre or two of ice forms on the surface? Accidents had to be modelled. Fifteen years after the New Mexico site opened, a drum of waste burst open, leaking radiation up an exhaust shaft and then for a kilometre or so above ground. (The cause was human error: someone had added a wheat-based cat litter into the drum instead of bentonite.) In late 2021, Posiva submitted all its studies and contingency plans to the Finnish government to seek an operating license. The document ran to 17,000 pages.

In the 2120s, once it has been filled, Onkalo will be sealed and turned over to the state. Other countries also plan to banish their nuclear waste into GDFs. Sweden has already selected its spot, Switzerland and France are trying to finalise theirs. The UK’s plans are at an earlier stage. A government agency, Nuclear Waste Services, is studying locations and talking to the people living there, but already the ballpark expenditure is staggering. “If the geology is simple, and we’re disposing of just high- and intermediate-level waste, then we’re thinking £20bn,” said Jonathan Turner, a geologist with Nuclear Waste Services. The ceiling – for now – is £53bn. “It’s a major project,” Turner said, “like the Chunnel or the Olympics.”

At the moment, Nuclear Waste Services is in discussions with four communities about the potential to host a GDF. Three are in Cumbria, and if the GDF does wind up in this neighbourhood, the Sellafield enterprise would have come full circle. The GDF will effectively entomb not just decades of nuclear waste but also the decades-old idea that atomic energy will be both easy and cheap – the very idea that drove the creation of Sellafield, where the world’s earliest nuclear aspirations began.

On one of my afternoons in Sellafield, I was shown around a half-made building: a £1bn factory that would pack all the purified plutonium into canisters to be sent to a GDF. We ducked through half-constructed corridors and emerged into the main, as-yet-roofless hall. Eventually, the plant will be taller than Westminster Abbey – and as part of the decommissioning process, this structure too will be torn down once it has finished its task, decades from now. I stood there for a while, transfixed by the sight of a building going up even as its demolition was already foretold, feeling the water-filled coolness of the fresh, metre-thick concrete walls, and trying to imagine the distant, dreamy future in which all of Sellafield would be returned to fields and meadows again.

This article was amended on 16 December 2022. An earlier version said the number of cancer deaths caused by the Windscale fire had been revised upwards to 240 over time. It should have been cancer cases, not deaths. This has been corrected.

Today's selection -- from Civilization: A New History of the Western World by Roger Osborne. Charlemagne, one of the most powerful rulers in European history, used Christianity to consolidate his power and unify the population under his rule:

“Charlemagne, who reigned for 46 years from 768, set out to conquer the territory of his neighbours and to convert them to Catholic Christianity 'with a tongue of iron'. In 772 he invaded Saxony along the same roads as Augustus 800 years earlier, and met with the same resistance. His armies destroyed the sacred places of Saxon worship, but because the Saxons had many leaders, they were almost impossible to defeat. Visits to Rome reinforced Charlemagne's ambition to build an empire, and provided him with a sense of epic and brutal power. The campaign against the Saxons grew more bitter as villages were forcibly relocated and hill-forts besieged and destroyed. Elements of the Saxon nobility were persuaded, by the prospect of more power over their own peasants, to betray their people to the Franks, and at Verden in 782, 4,500 Saxon prisoners were beheaded on the orders of Charlemagne.

“In the peace that was finally agreed, as Charlemagne's secretary and biographer Einhard wrote: 'The Saxons were to put away their heathen worship and the religious ceremonies of their fathers; were to accept the articles of the Christian faith and practice; and, being united to the Franks, were to form with them one people.' The same conditions were applied to most of the peoples of the western European mainland as Charlemagne's armies took the Germanic heartlands and pushed east as far as the Avar Khanate of Hungary, while also forcing the Arab armies in Spain back as far as the Ebro. Local traditions of worship, either pagan or Christian, were abolished and any diversion from the Catholic faith was strictly punished, as Charlemagne's 'Capitulary Concerning Saxony' states: 'If anyone follows pagan rites [or] ... is shown to be unfaithful to our lord the king, let him suffer the penalty of death.'

“At its height, Charlemagne's kingdom extended from the Pyrenees to the River Oder and from the North Sea to south of Rome. Western Europe, excluding only Britain and Iberia, was under one ruler, its boundaries were strictly drawn, and its frontiers were closed. Charlemagne took a strongly Frankish view of how this society should be organized. In the time of his grandfather, monks had come to the Frankish kings from Ireland and England, eager to preach to the pagans of Frisia and Saxony--both Willibrord and Boniface followed a tradition of wandering or peregrino Christians. But Charlemagne's conquests and his strict enforcement of Christianity changed the nature of their travels. Instead of converting pagans, clerics were engaged in the education and 'correction' of the population, to ensure that they followed Catholic ways. This was not simply an authoritarian process; there was a widespread belief that God was waiting to punish humanity for its sins, which must therefore be eradicated.

“Charlemagne felt his own need of instruction and looked once more to the now-celebrated Christian school of north-east England. Alcuin of York, inheritor of the scholarly reputation of Bede, travelled to the new palace complex at Aachen (characteristically built in the countryside) to be Charlemagne's spiritual adviser. And while his subjects must be shown the correct ways to be good Christians, they should also be good Franks. Subjection to the Lord God was matched by subjection, loyalty and deference to one's secular lord. Charlemagne was a master at creating an atmosphere of utter loyalty at his court combined with a system of formal friendship which served as a model for his aristocrats. But in this rigidly hierarchical Frankish society, any attempt to form communal organizations--guilds or brotherhood leagues, for example--was ruthlessly suppressed. The increased use of written instruction also allowed the imposition, just as in ancient Greece and Rome, of codified laws. Roman law was reintroduced either alongside, or in place of, the customary laws of local populations.

|

| The Bust of Charlemagne, an idealized portrayal and reliquary said to contain Charlemagne's skull cap, is located at Aachen Cathedral Treasury, and can be regarded as the most famous depiction of the ruler. |

Charlemagne was declared Caesar, or emperor, on Christmas Day 800 by Pope Leo. This was less an anointment of a subject king than a desperate attempt by the pope to endear himself to the most powerful man in Europe, and to gain some influence over the direction of Christendom. Despite Stephen's efforts of 50 years earlier, western Christianity was firmly in the hands of northerners--principally Charlemagne and whichever scholars he chose to come to his court. The pope needed entry into this charmed circle. The learned monks at Aachen were charged with giving spiritual direction to Charlemagne's kingdom, but they also helped to create a mythic history of western Christianity, with Charlemagne as its apogee. This was entirely understandable; it was important for the Aachen court to create a 'civilization story' that explained their own place in history. Alcuin, in particular, was aware of Viking raids on the coast of his homeland and took these as a sign of God's displeasure with his flock. Einhard, Charlemagne's contemporary biographer, understood that the emperor had been granted great power precisely in order to bring the faithful to heel.

“These writers followed Bede's lead in seeing pagan darkness both in the past and all around. They described the Merovingian centuries as an age of darkness, barbarism and ignorance, allowing later writers to speak of a 'Carolingian renaissance' in the eighth century. Both were a travesty of the truth, but fuelled the Franks' self-importance and gave justification to the severe brutality they had handed out. Even the Carolingian minuscules, the lower case Roman alphabet attributed to Charlemagne's court, emerged from the labours of generations of scribes who worked at the courts of 'barbarian' kings, while the development or reinstatement of 'correct' Latin by Alcuin and others (who came from regions where Latin had not been spoken for centuries) presented a new barrier between intellectual and ordinary life. People in Francia (and in Italy and Spain) in the early ninth century assumed they were speaking Latin which they had inherited from the Romans. But their Latin was an early form of French, and unintelligible to Latin scholars; Alcuin dismissed it as barbarous. Church Latin therefore became a language that was spoken by no ordinary people, but was the universal language of an educated elite and the required language of the Catholic liturgy--it was the language in which man spoke to God.

“While Charlemagne wanted to create a Christian society in the form of a Holy Empire, Christian monks and bishops had begun to think about new political structures. In particular they read St Augustine's City of God, which told them they should not be content to live in a wicked world, but should aim to teach others the way that the world should be governed. The Christian church began to seek the establishment of a state governed by the doctrines of Christianity, just as Charlemagne wanted to recreate the majesty of the Roman empire by uniting the see of Rome with his own empire in the north. Charlemagne's power and ambition gave direction to the course of western history for the next 500 years by making the church in Rome part of western, rather than Mediterranean, Europe. Charlemagne created the state that many in Europe desired--a Christian empire centred on a court where piety and learning were valued, while converting or making war on the heathen tribes on its borders. The price was the quashing of diversity and granting the church an ever-growing influence in politics and education. Charlemagne had recreated Latin Christendom and put Christianity at the centre of the state's affairs, but he also put the state at the centre of the church's affairs.

“The reign of Charlemagne marks the end of the first phase of the Middle Ages, but his empire did not last. In 843 Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious divided his empire between his own three sons--the Franks were effectively divided into a western (French) kingdom, an eastern (German) kingdom, and a middle kingdom. The resulting conflicts were exacerbated by the increasing raids of Scandinavian northmen or Vikings and by incursions by Magyars and Slavs. But the power of the German element of the Franks was reasserted by the emperor Otto I, who was king of the Germans from 936, and emperor from 962 until his death in 973. Otto's armies defeated the invading Magyars, pushed the Slavs back to the Balkans and took over most of Italy. The Germanic people became, and remained, the dominant force in central Europe. By 1000, the Scandinavian raiders and people had become integrated into the Christian culture of western Europe.”

|

|||

| author: Roger Osborne | |||

| title: Civilization: A New History of the Western World | |||

| publisher: Pegasus Books | |||

| date: | |||

| page(s): 148-151 |

By Thorsten Polleit

November 18, 2023

On 15 November 1923 decisive steps were taken to end the nightmare of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic: The Reichsbank, the German central bank, stopped monetizing government debt, and a new means of exchange, the Rentenmark, was issued next to the Papermark (in German: Papiermark). These measures succeeded in halting hyperinflation, but the purchasing power of the Papermark was completely ruined. To understand how and why this could happen, one has to take a look at the time shortly before the outbreak of World War I.

Since 1871, the mark had been the official money in the Deutsches Reich. With the outbreak of World War I, the gold redeemability of the Reichsmark was suspended on 4 August 1914. The gold-backed Reichsmark (or “Goldmark,” as it was referred to from 1914) became the unbacked Papermark. Initially, the Reich financed its war outlays in large part through issuing debt. Total public debt rose from 5.2bn Papermark in 1914 to 105.3bn in 1918.1 In 1914, the quantity of Papermark was 5.9 billion, in 1918 it stood at 32.9 billion. From August 1914 to November 1918, wholesale prices in the Reich had risen 115 percent, and the purchasing power of the Papermark had fallen by more than half. In the same period, the exchange rate of the Papermark depreciated 84 percent against the US dollar.

The new Weimar Republic faced tremendous economic and political challenges. In 1920, industrial production was 61 percent of the level seen in 1913, and in 1923 it had fallen further to 54 percent. The land losses following the Versailles Treaty had weakened the Reich’s productive capacity substantially: the Reich lost around 13 percent of its former land mass, and around 10 percent of the German population was now living outside its borders. In addition, Germany had to make reparation payments. Most important, however, the new and fledgling democratic governments wanted to cater as best as possible to the wishes of their voters. As tax revenues were insufficient to finance these outlays, the Reichsbank started running the printing press.

From April 1920 to March 1921, the ratio of tax revenues to spending amounted to just 37 percent. Thereafter, the situation improved somewhat and in June 1922, taxes relative to total spending even reached 75 percent. Then things turned ugly. Toward the end of 1922, Germany was accused of having failed to deliver its reparation payments on time. To back their claim, French and Belgian troops invaded and occupied the Ruhrgebiet, the Reich’s industrial heartland, at the beginning of January 1923. The German government under chancellor Wilhelm Kuno called upon Ruhrgebiet workers to resist any orders from the invaders, promising the Reich would keep paying their wages. The Reichsbank began printing up new money by monetizing debt to keep the government liquid for making up tax-shortfalls and paying wages, social transfers, and subsidies.

From May 1923 on, the quantity of Papermark started spinning out of control. It rose from 8.610 billion in May to 17.340 billion in April, and further to 669.703 billion in August, reaching 400 quintillion (that is 400 x 1018) in November 1923.2 Wholesale prices skyrocketed to astronomical levels, rising by 1.813 percent from the end of 1919 to November 1923. At the end of World War I in 1918 you could have bought 500 billion eggs for the same money you would have to spend five years later for just one egg. Through November 1923, the price of the US dollar in terms of Papermark had risen by 8.912 percent. The Papermark had actually sunken to scrap value.

With the collapse of the currency, unemployment was on the rise. Since the end of the war, unemployment had remained fairly low — given that the Weimar governments had kept the economy going by vigorous deficit spending and money printing. At the end of 1919, the unemployment rate stood at 2.9 percent, in 1920 at 4.1 percent, 1921 at 1.6 percent and 1922 at 2.8 percent. With the dying of the Papermark, though, the unemployment rate reached 19.1 percent in October, 23.4 percent in November, and 28.2 percent in December. Hyperinflation had impoverished the great majority of the German population, especially the middle class. People suffered from food shortages and cold. Political extremism was on the rise.

The central problem for sorting out the monetary mess was the Reichsbank itself. The term of its president, Rudolf E. A. Havenstein, was for life, and he was literally unstoppable: under Havenstein, the Reichsbank kept issuing ever greater amounts of Papiermark for keeping the Reich financially afloat. Then, on 15 November 1923, the Reichsbank was made to stop monetizing government debt and issuing new money. At the same time, it was decided to make one trillion Papermark (a number with twelve zeros: 1,000,000,000,000) equal to one Rentenmark. On 20 November 1923, Havenstein died, all of a sudden, through a heart attack. That same day, Hjalmar Schacht, who would become Reichsbank president in December, took action and stabilized the Papermark against the US dollar: the Reichsbank, and through foreign exchange market interventions, made 4.2 trillion Papermark equal to one US Dollar. And as one trillion Papermark was equal to one Rentenmark, the exchange rate was 4.2 Rentenmark for one US dollar. This was exactly the exchange rate that had prevailed between the Reichsmark and the US dollar before World War I. The “miracle of the Rentenmark” marked the end of hyperinflation.3

How could such a monetary disaster happen in a civilized and advanced society, leading to the total destruction of the currency? Many explanations have been put forward. It has been argued that, for instance, that reparation payments, chronic balance of payment deficits, and even the depreciation of the Papermark in the foreign exchange markets had actually caused the demise of the German currency. However, these explanations are not convincing, as the German economist Hans F. Sennholz explains: “[E]very mark was printed by Germans and issued by a central bank that was governed by Germans under a government that was purely German. It was German political parties, such as the Socialists, the Catholic Centre Party, and the Democrats, forming various coalition governments that were solely responsible for the policies they conducted. Of course, admission of responsibility for any calamity cannot be expected from any political party.”4 Indeed, the German hyperinflation was manmade, it was the result of a deliberate political decision to increase the quantity of money de facto without any limit.

What are the lessons to be learned from the German hyperinflation? The first lesson is that even a politically independent central bank does not provide a reliable protection against the destruction of (paper) money. The Reichsbank had been made politically independent as early as 1922; actually on behalf of the allied forces, as a service rendered in return for a temporary deferment of reparation payments. Still, the Reichsbank council decided for hyperinflating the currency. Seeing that the Reich had to increasingly rely on Reichsbank credit to stay afloat, the council of the Reichsbank decided to provide unlimited amounts of money in such an “existential political crisis.” Of course, the credit appetite of the Weimar politicians turned out to be unlimited.

The second lesson is that fiat paper money won’t work. Hjalmar Schacht, in his 1953 biography, noted: “The introduction of the banknote of state paper money was only possible as the state or the central bank promised to redeem the paper money note at any one time in gold. Ensuring the possibility for redeeming in gold at any one time must be the endeavor of all issuers of paper money.”5 Schacht’s words harbor a central economic insight: Unbacked paper money is political money and as such it is a disruptive element in a system of free markets. The representatives of the Austrian School of economics pointed this out a long time ago.

Paper money, produced “ex nihilo” and injected into the economy through bank credit, is not only chronically inflationary, it also causes malinvestment, “boom-and-bust” cycles, and brings about a situation of over-indebtedness. Once governments and banks in particular start faltering under their debt load and, as a result, the economy is in danger of contracting, the printing up of additional money appears all too easily to be a policy of choosing the lesser evil to escape the problems that have been caused by credit-produced paper money in the first place. Looking at the world today — in which many economies have been using credit-produced paper monies for decades and where debt loads are overwhelmingly high, the current challenges are in a sense quite similar to those prevailing in the Weimar Republic more than 90 years ago. Now as then, a reform of the monetary order is badly needed; and the sooner the challenge of monetary reform is taken on, the smaller will be the costs of adjustment.

—

1.See here and in the following H. James, “Die Reichbank 1876 bis 1945,” in: Fünfzig Jahre Deutsche Mark, Notenbank und Währung in Deutschland seit 1948, Deutsche Bundesbank, ed. (München: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1998), pp. 29 – 89, esp. pp. 46 – 54; C. Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation, A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany (Northampton: John Dickens & Co., 1968 [1931]); also F.D. Graham, Exchange, Prices, And Production in Hyper-Inflation: Germany, 1920 – 1923 (New York: Russell & Russell, 1967 [1930]).

2.To be sure: It is a “400” with 18 zeros: 400,000,000,000,000,000,000. In American and French nomenclature, it is “quintillion,” in English and German nomenclature one would speak of “trillion,” or a “thousand billion” times 1,000. In this article, the American nomenclature will be used throughout.

3.For further details see Bresciani-Turroni, Economics of Inflation, chap. IX, pp. 334–358.

4.H.S. Sennholz, Age of Inflation (Belmont, Mass.: Western Islands, 1979), p. 80.

5.H. Schacht, 76 Jahre meines Lebens (Kindler und Schiermeyer Verlag, Bad Wörishofen, 1953), pp. 207-208. My translation.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org are not necessarily those of the Mises Institute.

By James Howard Kunstler

November 11, 2023

https://kunstler.com

Of course, you already sense that the 2024 election will be a freaky event, if it happens at all. If it’s not America’s last election altogether, it may be the last one that follows the traditional format that has signified stability in our country’s high tide as a great power: that is, a contest between Republicans and Democrats. Both parties are likely to crash and burn in the year ahead, along with a whole lot of other things on the tottering scaffold of normal life.

Have you lost count yet of the number of things in our country that are broken? The justice system. Public safety. Education. Medicine. Money. Transportation. Housing. The food supply. The border. The News business. The arts. Our relations with other countries. That’s just the big institutional stuff. At the personal scale its an overwhelming plunge in living standards, loss of incomes, careers, chattels, liberties. . . poor health (especially mental health). . . and failing confidence in any plausible future.

The reasons behind all that failure and loss are pretty straightforward. The business model for operating a high-tech industrial economy is broken. That includes especially the business model for affordable energy: oil, gas, nuclear, and the electric grid that runs on all that. We opted out of an economy that produced things of real value. We replaced that with a financial matrix of banking fakery. That racket made a very few people supernaturally wealthy while incrementally dissolving the middle-class. We destroyed local and regional business and scaled up what was left into super-giant predatory companies that can no longer maintain their supply chains. Fragility everywhere in everything.

Bad choices all along the way, you could say, but perhaps an inexorable process of nature. Things are born, they grow, they peak, they decline, they die. The difference this time is the scale of everything we do is so enormous that the wreckage is also epic. It’s happening in Western Civ at the moment, led by its biggest nation state, us, the USA, but it will eventually go global, spread to the BRICs and the many countries that will never actually “develop.”

I started writing about the fiasco of suburbia decades ago, and now the endgame of that living arrangement is in view. The dissolving middle class has gotten priced-out of motoring. Motoring is the basis of the suburban living arrangement. No motoring, no suburbia. It’s that simple. There was widespread belief among idealistic reformers that suburbia could just be “retrofitted” for “smarter” daily life, but that dream is over. The capital (money) is not there to fix it, and there’s no prospect that we’ll somehow come up with it as far ahead as we can see.

So far, the collapse of suburbia has happened in slow motion, but the pace is quickening now and it’ll get supercharged when the bond markets go down, as they must, considering the country’s catastrophic fiscal circumstances. That will produce exactly the zombie apocalypse telegraphed in all those movies and TV series over recent years: normality overrun by demonic hungry ghosts. Every day in suburbia will be Halloween, and not in a fun way.

All this is apprehended to some degree by the increasingly frightened public, though they have a hard time articulating it within any of the popular frameworks presented by politics, religion, or what appears lately to be extremely corrupt science. The people see what’s coming but they can’t make sense of it, and the stress makes a great many of them insane. Without a way to construct a coherent view of reality, or tell the difference between what’s real and what’s not, they behave accordingly: anything goes and nothing matters.

In the face of all this the two big political parties are helpless and clueless. The Democrats have made themselves into a giant feedback loop amplifying the poor mental health of their constituents. They are in CrazyLand, where there are no boundaries anymore, and to insist that there should be is an affront that gets you cancelled. They are in upside-down inside-out world. Hillary Clinton demonstrated this perfectly the other day on ABC’s The View when she accused her party’s opponents of trying to “do away with elections, trying to do away with the opposition, and do away with a free press….” It’s hard to imagine a more impressive lack of self-awareness.